CREATING "JESU PASCHGON KIA"

As we began to look more carefully into the contents of Box 331, we discovered six different versions of the hymn “Jesu paschgon kia.” One of these was a photocopy from the Unity Archives of the Moravian Church (Archiv der Brüder-Unität) in Herrnhut.20Interestingly, the Herrnhut version of the hymnal provides an important piece of information that would not have been discovered if not for the inquiries of Bernice Miller and Dorothy Davids of the Stockbridge community. It was their knowledge of the existence of the hymns that led linguist Carl Masthay to search for more Mohican-language materials.21 This particular manuscript is the only copy that lists the names of some of the hymn writers. The name “Gottlob Büttner,” penned neatly under “Jesu paschgon kia” in the Herrnhut manuscript, provided the clue that we needed to unlock a substantial textual history scattered across the vast Moravian records. Without this attribution, we would not have known that this was the same hymn written by the young missionary Gottlob Büttner and mentioned in the Shekomeko mission diary in November 1744 as being the first hymn written in Mohican. The subsequent textual history of “Jesu paschgon kia” alone is a fascinating story, but when it is linked to the broader context of the mission, and particularly the reach of broad transatlantic currents into the small community of Shekomeko, it is possible to see how such texts represent extensive webs of interconnection and new forms of community while also testifying to the deep strains placed on Native communities by the forces of empire that originated far from Shekomeko.

The genesis of “Jesu paschgon kia” began with Büttner’s first visit to Shekomeko in January 1742, within weeks of his twenty-fifth birthday. The following month, Büttner accompanied his missionary colleague, Christian Rauch, and a delegation of men from the community to Oley, Pennsylvania, where Moravian leader Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf had called an ecumenical synod hoping to unite the diverse communities of Protestants into one Church of God in the Spirit. He failed in that effort, but the three Mohican men were baptized at the gathering, taking the names Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. That fall, Büttner married Anna Margaretha Bechtel in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and the following month the newlyweds took up residence in Shekomeko along with several other Moravian couples.22The young Moravian missionaries—men and women—were quite different from their Anglo-Protestant counterparts. They were counseled by Moravian leadership to preach first with their actions and only later with their words. They were to earn their living by working among their Native hosts. Any additional necessities were supplied through the work of the communal economy at Bethlehem. Not insignificantly, the Moravian missionaries to Shekomeko did not come as part of a larger white community looking to settle on Native lands. Thus, it was almost two years between the time Rauch first encountered two Mohican men, Wasamapah and Mamanetthekan, in New York City in the summer of 1740 and his initial effort at preaching in Shekomeko.23

Music was essential to Moravian religious practice, and so hymn singing would certainly have been part of the missionaries’ own devotions from their first arrival. However, because of the Moravians’ relatively cautious missionary policy, the first mention of hymn singing as part of communal services together with Shekomeko residents dates to an October 1742 gathering during which Büttner preached and Johannes (also known as Wasamapah/Tschoop) translated. The service concluded with hymn singing, presumably in German or Dutch. Anna Margaretha Büttner’s rapid progress learning Mohican facilitated strong relationships, particularly with the women of Shekomeko, and within a year of her arrival, her husband noted that she was speaking in Mohican.24By late fall 1744, Gottlob Büttner noted in his diary that, with the assistance of the Holy Spirit, he was writing verses in Mohican and also translating hymns, including “O King of Glory and the Lord,” or “O König der Ehren Jesu Christ.”25 A week later, the Shekomeko community sang hymns for the first time in Mohican. Büttner continued his work on two more verses during the December visit of a delegation of Mohicans from Stockbridge who came to attend the burial of a murdered relative. We can reasonably presume that “Jesu paschgon kia” was one of these hymns. While he was working on these three verses, Büttner was already sick with the pulmonary ailment that would lead to his death just months later in late February 1745. The young Mohican man Joshua/Nanhun, who would later write the first Native-authored Mohican hymns, was a key figure in the early mission community, often serving as the bearer of important messages between communities. It was he who brought the news of Büttner’s death to Bethlehem in March 1745.26

The earliest known extant version of “Jesu paschgon kia” was put to paper the following month as part of a musical memorial to the deceased missionary. When a party of Shekomeko residents departed Bethlehem for home in March 1745, they performed a cantata, incorporating the verses written by Büttner just months earlier.27This version shows an early attempt at a written form of Mohican, which would later be refined through at least five subsequent revisions of the text. The last mention of revising “Jesu paschgon kia” we have dates to September 1748, when a party was preparing to undertake a visit to the multiethnic Native communities at Shamokin and Wyoming (Pennsylvania) and Moravian missionary Johann Christoph Pyrlaeus (a convert from Lutheranism and a gifted musician and linguist), Joshua, and the community of Native Moravians worked to produce better versions of the Mohican hymns.28

The collaborative process that led to multiple revisions of the Mohican hymns can be more fully fleshed out by charting various developments in the mission community between Büttner’s composition of “Jesu paschgon kia” in late 1744 and the 1748 revision. A major factor shaping the collaboration was the upheaval in transatlantic imperial politics, one manifestation of which was the eruption of King George’s War in 1744. During this time, the European Moravians turned over worship services to Native leaders, who then led the push for the creation of a language school in which they would instruct missionaries in Mohican, and European Moravian leaders in Bethlehem invested significant energy in hymn singing and language acquisition. All of these factors resulted in increased collaboration between European and Native Moravians as well as a significant improvement in the Moravian missionaries’ facility with the Mohican language, evident in the revision history of the Mohican hymns.

The period during which Büttner first composed Mohican verses and the Native community began to learn them was an especially difficult one. The religious revivals that swept the Northeast in the 1730s and 1740s were pitting minister against minister and transforming the colonial religious landscape, and one result of this upheaval was a rise of anti-Moravian sentiment among other colonists. War in the colonies (an offshoot of the larger War of the Austrian Succession) fueled increased hostility toward Native peoples in the Northeast. Many of the Moravians’ New York neighbors suspected that nearby Native communities had allied with the French and were plotting to kill their white neighbors—and they took particular offense that one missionary, Christian Friedrich Post, had married a Native woman. These forces led first Connecticut and then New York to ban Moravians from preaching.29

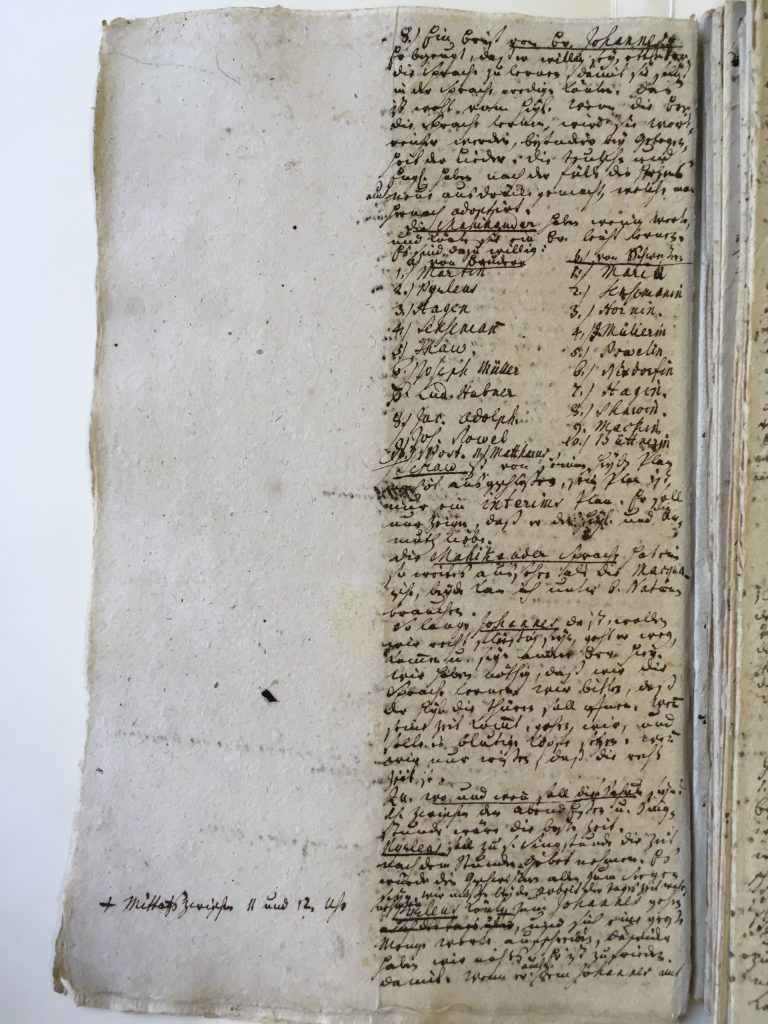

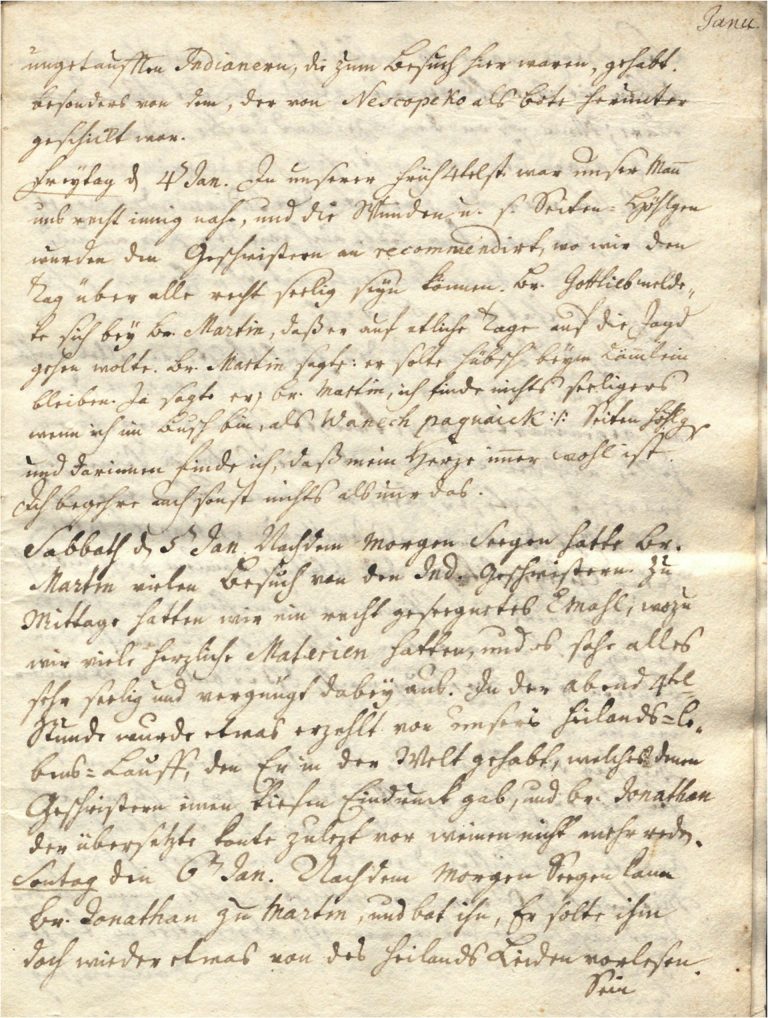

Büttner’s death and the impending departure of the other missionary couples prompted intense debate among the Shekomeko community. The question of the town’s fate loomed over the Native and European Moravians. Community records from the summer of 1745 through the summer of 1746 document a period of particularly close work between Native and European Moravians, one result of which can be seen in the revised Mohican verses contained in two 1746 collections of hymns (Figure V). The unusual openness of Moravian missionaries to Native collaboration was arguably one local ripple of faraway events. When the Moravians were first banned from preaching and then forced to leave Shekomeko, Native leaders assumed those responsibilities. Abraham, Johannes, and Isaac regularly led services, hosted feasts for Native and European visitors, and sang Mohican verses.30At a service led by Abraham, the community learned to sing a verse composed by Büttner, “Gaquay npettamechnau” (Recording II).31Ironically, the precariousness of the Shekomekoans’ situation led to a more substantial integration of Native communities into Bethlehem, the North American hub of the transatlantic Moravian community, as delegations of Shekomekoans visited frequently, often spending several weeks at a time in Bethlehem and sometimes leaving children in the care of the community.32

During the summer of 1745, intense discussions took place among Shekomekoans over communal meals, in sweat lodges, and in homes as they weighed their options to stay put, move to the Susquehanna River at Wyoming, or join the Moravians at Bethlehem. The debate was front and center in Bethlehem as well. In August, two representatives were sent from Bethlehem to invite the Shekomekoans to choose a delegate who would represent the community at an upcoming synod to be held in Bethlehem. Jonathan, son of Shekomeko leader Abraham, was the community’s choice. As described by the missionaries, the selection and function of synod delegates would have borne a strong resemblance to models of Native leadership.33Jonathan relayed a request from Johannes that the missionaries become his pupils in the study of Mohican, for “when they learn the language, it will become richer in words, particularly through hymns.” Eleven men, including August Spangenberg (known as Joseph), and ten women from Bethlehem expressed their willingness to enroll in the language school. Johannes planned to meet for an hour in the morning with Pyrlaeus to work on vocabulary, pronunciation, and writing hymns. Then in the evening, Pyrlaeus would hold classes with the enrolled pupils from Bethlehem. Interestingly, Pyrlaeus had learned from his study of Mohawk that he should not “handle the matter in a learned way” but rather “shall begin the thing with the Savior’s blessing.”34 Pyrlaeus commemorated the start of the school by writing a poem in German and a hymn verse in Mohican.35

At a December synod held in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Jonathan also relayed a request from the Shekomeko community for a teacher in Shekomeko. The necessity for teachers was made clear to the synod by the inclusion of missionary Martin Mack’s report of seeing a receipt that a neighboring white settler had given to a Native Shekomeko resident. “There was not so much as a letter therein,” wrote Mack, “but only foolish Scribling, by which means they endeavor to cheat the Indian Br. & so have their unjust demands paid twice.”36 Two years later, Joshua was among a number of Gnadenhütten residents requesting the creation of a German school, at which the instructor Pyrlaeus later reported that the students requested Mohican verses to be written out for them.37

The more frequent and lengthy visits of Shekomekoans in Bethlehem in 1745 and 1746 provided further opportunities for collaboration. By the spring of 1746, most Shekomekoans had decided it was untenable to remain in their village. In April, a party of roughly twenty community members set out from Shekomeko for Bethlehem, where they would settle, thus facilitating closer collaboration. These political and educational impulses—the ban on Euro-Moravian preaching as well as Mohicans’ desire for literacy and request for teachers who had a command of the Mohican language—all supply the context for the continued revision of the Mohican-language hymns.38

Amid the upheaval, there was considerable work on the Mohican hymns. Three of the extant hymn booklets date to 1746, and analysis of these booklets enables us to track the progress of language acquisition among the missionaries. A new version of the hymnal was created in February 1746, and then two further copies sometime later that year, as can be deduced by changes to the text that show the missionaries’ greater facility with Mohican (see Figure V).39Additional evidence of this improvement in the missionaries’ language skills and the deepening of collaborative relationships comes from an analysis of the hymn texts themselves. According to Chris Harvey, the six extant versions of “Jesu paschgon kia” demonstrate a process of revision (see Linguistic Analysis). All versions contain some grammatical irregularities, yet a careful analysis of the revisions argues for a close collaboration between Native speakers and several different copyists, who likely had differing levels of linguistic proficiency and may have varied as well in how they chose to represent Mohican sounds with German phonetics. The changes may reflect different versions used by the community over time or an attempt to create a definitive text that would be standardized.40

One of the last direct mentions of the hymn “Jesu paschgon kia” dates to September 1748, and the work done on this occasion likely produced the Herrnhut hymnal (Figure VI).41 By that time, most Mohicans from Shekomeko had settled in a new community on Delaware land secured by the Moravians and called Gnadenhütten, or “tents of grace.” Joshua had been named manager of the community’s external affairs and – together with his second wife, Bathsheba – was responsible for sending messages to other Native communities through belts of wampum.42

Interestingly, in the Herrnhut hymnal, a number of the hymns are attributed to Joshua and Bathsheba, working with Pyrlaeus, and it may be that the production and transmission of hymns mirrored the production and transmission of wampum. A vision Joshua experienced in December 1747 suggests the linkage between his role as emissary, the continued power of dreams and visions, and the possibility that the Christian message conveyed in the Mohican-language hymns attributed to Joshua and Bathsheba would be the means of forging bonds of kinship and community among Indigenous people. In the vision, a group of Native visitors from the nearby Lenape settlement of Meniolagomekah appeared to him, and an elderly man asked to hear about the Christian God. When Joshua told the story of Jesus and the power of his blood, the man responded, “this is an important word.” Several weeks after Joshua’s vision, a party arrived from Meniolagomekah, and by the following summer, the village leader and many of his relatives had settled at Gnadenhütten. New Native settlers like these came to the Moravian communities for a variety of reasons, not least of which was the ideal of an interethnic community articulated in the creation and promulgation of Mohican hymns.43

In the late summer of 1748, Joshua, Pyrlaeus, and the community of Native Christians set to work creating a revised version of the hymnal.44The work was done in anticipation of Moravian bishop Johannes von Watteville’s visit to Gnadenhütten before undertaking a journey to the settlements at Shamokin and Wyoming, farther up the Susquehanna River. The delegation was to seek the renewal of an earlier covenant, interestingly, one that had been undertaken in fall 1742 by Moravian leader Zinzendorf and newly appointed missionary David Zeisberger, who were accompanied by Joshua and David, son of Shekomeko leader Abraham.45Mohican kin of the Shekomekoans could be found at both of these multiethnic communities. Much diplomatic energy was demanded on all sides to create, sustain, and reconfigure relationships among and between various different Native and European groups.

By this time, the Gnadenhütten community had grown to several hundred residents, primarily Mohican and Lenape.46 To prepare the hymns, Pyrlaeus proposed that he and Joshua would lead several Singstunden (singing services). As they worked, “any unclear words, or incomprehensible matters would be corrected,” after which Joshua and Pyrlaeus would first speak the words and then sing them through, and then all those gathered would sing the verse until they were able to sing it well. The diarist noted that the congregation was happy with the singing and that a number of words were changed.47

The Moravian embassy to Shamokin that fall was just one of a host of diplomatic visits undertaken all through 1748.48New and prospective Native settlers—as well as staunch opponents—arrived at Gnadenhütten from Meniolagomekah, Wechquadnach, Pachgatgoch, Wyoming, Shamokin, and other nearby Native settlements. Gnadenhütten residents traveled to Bethlehem to meet the Greenlanders and Arawaks who were visiting there. They also regularly traveled to visit family and friends who had remained in their home villages throughout the Delaware, Hudson, and Housatonic Valleys, and Gnadenhütten’s people ventured up the Susquehanna to the relatively recently founded multiethnic communities. Moravian leaders including Spangenberg, Watteville, and Pyrlaeus traveled to Philadelphia to meet with a Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) delegation and renew the covenant between the Brethren and the Six Nations established in 1742.49

Untangling the full complexity of diplomatic aims at play is unnecessary here. For our purposes, what is significant is that the creation of a Mohican-Moravian hymnody served distinctive but overlapping functions for the Natives and Europeans engaged in hymn production and use. As Patrick M. Erben has argued persuasively, the Moravian project of polyglot hymnody derived from a broader strain of German Pietist mysticism that envisioned overcoming the linguistic and political chaos unleashed at the Tower of Babel through the cultivation of a harmony of spirit. During the mid-1740s, the Bethlehem congregational records were filled with references to singing hymns in up to eighteen different languages during the same worship service.50 On a more earthly plane, the Moravian investment in Native-language hymnody demonstrates the missionaries’ understanding on some level of the significance of song and ceremony to Native communities and the powerful impression made when Europeans invested in learning Native ways.

Viewed in the light of the long-standing Mohican diplomatic strategy of serving as intermediaries between neighboring peoples who were often more populous and powerful, Mohican contributions to the creation of Native-language hymnody can be seen as a central prong of their effort to maintain that role. Hymns, like wampum, carried the message of the community with the aim of cementing relational ties. Creating and singing the hymns together with European Moravians bound the communities together as one people, with the stamp of spiritual efficacy from a newly introduced spirit being, the Moravians’ Heiland (Savior), whose powers Joshua attested to in a series of verses about the power of the Savior’s blood to strengthen and heal.51Facilitating the creation of Mohican-, Mohawk-, and Munsee-language hymns and their introduction among non-Moravian-affiliated Native communities should be seen not simply as traditional Christian evangelism but also as representing a continuity of Mohican self-understanding. Mohican relationships with many different peoples were their diplomatic currency, and hymns were a representation of that currency. Thus, what looks like factionalism—some Mohicans staying in Shekomeko, others moving to Wyoming—might be perceived rather as a strategic placement of human resources to preserve broad Mohican influence. The Mohican verses were regularly sung when members of the community traveled abroad, and we suspect they constituted the beginnings of a new ritual intended to express and sustain relationships.52

The production of Mohican-language hymnals was clearly a collaborative project, representing a range of aims—some convergent, some divergent—on the part of Native and European Moravians. Though further archival research will certainly yield additional insights into the creation of Mohican hymns within the larger context of Native and European diplomacy, our efforts to re-sound the hymns have shed an altogether different light on the meanings and resonances of the eighteenth-century Mohican hymn texts in the present day. And these hymn texts, as their original creators intended, continue to function to build and sustain relationships.

The first document contains a reference to Johannes’s offer to start a Mohican language school for European Moravians and the twenty Bethlehem residents who expressed interest. The second document references Gottlieb’s practice of singing “Wanech Paquaick” (Beautiful Wounds) while hunting.