Hidden In Plain Sight: Escaped Slaves in Late Eighteenth- and Early Nineteenth-Century Jamaica

Simon P. NewmanSimon P. Newman is Sir Denis Brogan Professor of American History at the University of Glasgow. The author would like to thank David Ely, Anthony King, and Marenka Thompson-Odlum for their contributions to the article, and Kelly Crawford and Kim Foley for invaluable technical support at the Omohundro Institute. For their comments and suggestions on earlier drafts, the author is grateful to audiences at the Early Modern Works-in-Progress group at the University of Glasgow, the University of Sydney, the University of Melbourne, the University of Cambridge, the Early Modern Studies Institute (University of Southern California and Huntington Library), the OI Colloquium in Williamsburg, the conference of the European Early American Studies Association, and the anonymous readers for the William and Mary Quarterly.

artwork by Anthony King, maps by David Ely, and video and photography by Marenka Thompson-Odlum

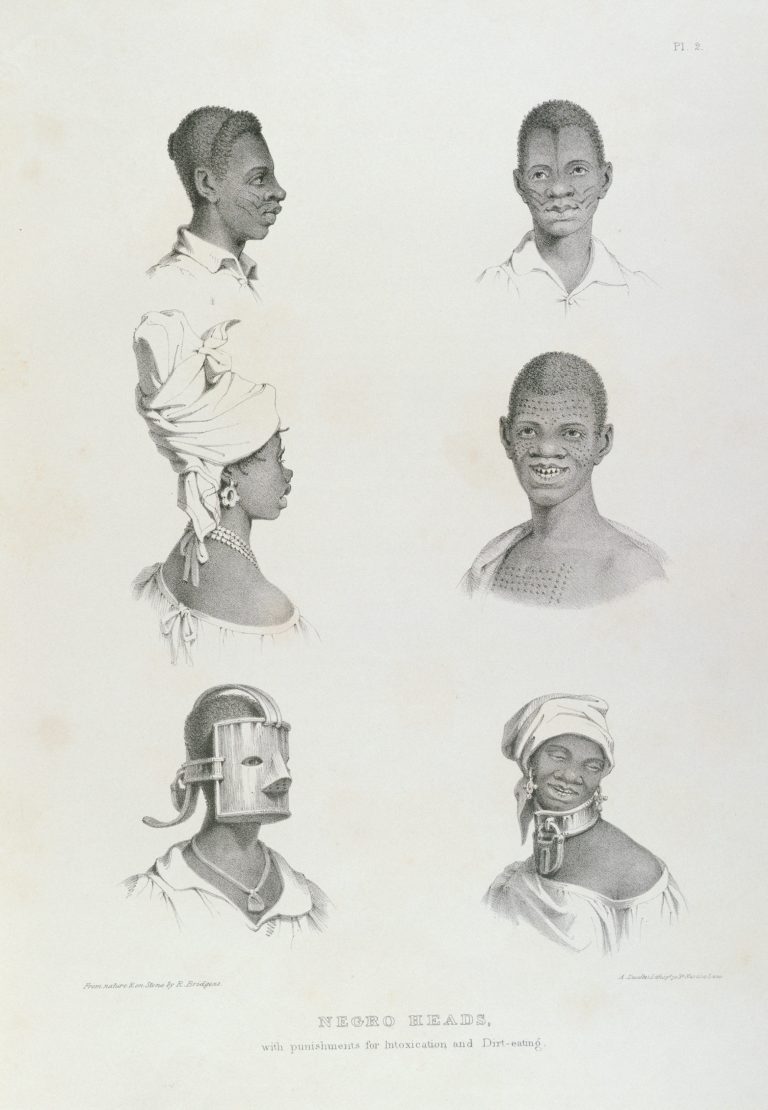

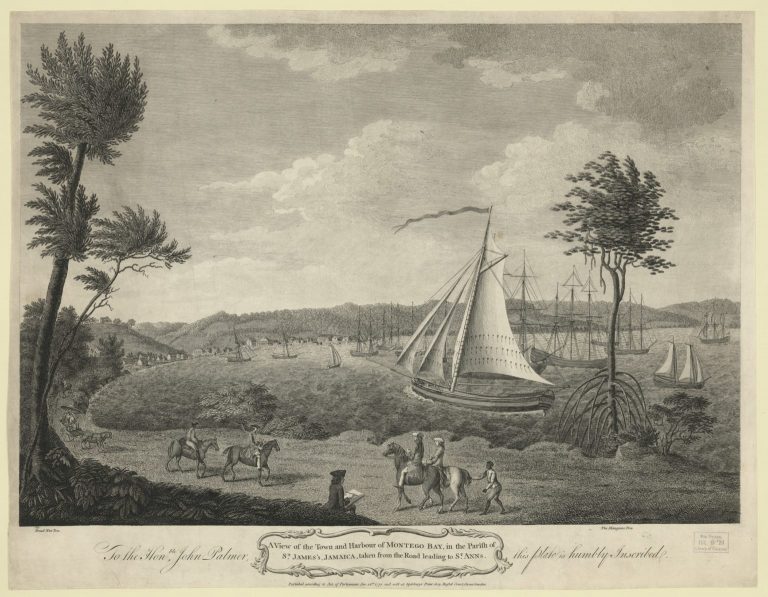

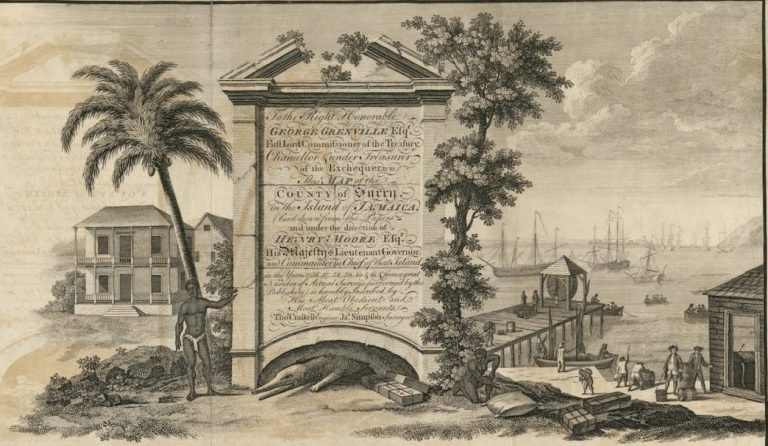

1THE experience of daily life in Jamaica’s slave society remains elusive. Historians depend upon sparse written and pictorial accounts created by a small number of white and a far smaller number of black people, and scholars face the challenge of interpreting these incomplete documentary records in order to make comprehensible to modern readers not just the sights, sounds, and experiences of Jamaica as it was but, more significantly, how both black and white Jamaicans interpreted and made sense of the world they saw, heard, and sensed.1 A variety of motivations and agendas informed the construction of travel narratives, histories, diaries, correspondence, and artistic images by those who recorded life and society in the British Caribbean. Employing sound and video recordings as well as enhanced eighteenth- and nineteenth-century artwork and maps, all in digital format, this article will challenge readers to think about Jamaican society in new ways. It will explore how white men saw and experienced the island and its population in order to enhance our understanding of how enslaved men, women, and children who attempted long-term escapes were able to achieve varying degrees of liberty and self-determination at the heart of Britain’s largest slave society. Selecting and presenting new media does not in and of itself offer a transformative vision of the past. However, by seeking to give 2the reader new ways of experiencing and interrogating the human landscape of Jamaica, this article will enhance our critical understanding of both the lived experience of the ideological system upon which slavery rested and the ways in which some of the enslaved negotiated and resisted their bondage.2

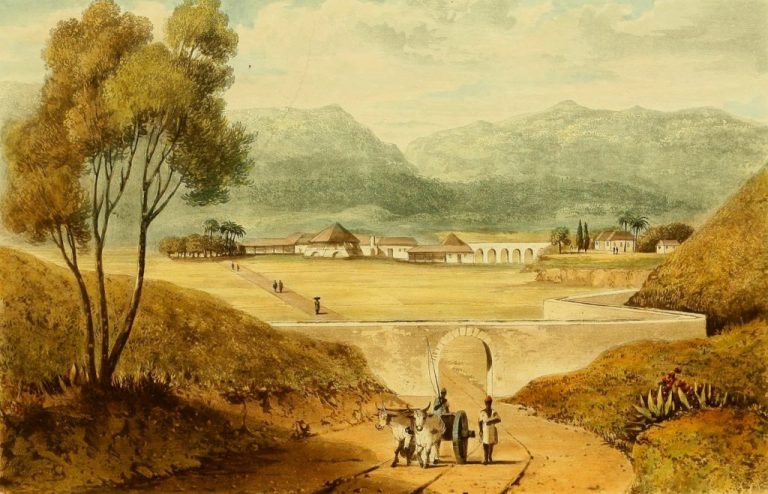

Both eighteenth-century and modern media present their own interpretive challenges, and this article will highlight the problems inherent in historical sources while also considering the merits and weaknesses of modern pictorial, aural, and video materials. In terms of historical artwork, for example, the rise of British abolitionism and its use of visual representations of the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade encouraged those who benefited from slavery to present images of the British Caribbean as a peaceful and harmonious society. In doing so, they followed in the wake of earlier visual efforts to depict the Caribbean’s peoples and landscapes in such a way that Britons would be persuaded to move there. Both sorts of art intentionally obscured Jamaica as it was seen and experienced by its free and enslaved inhabitants alike, especially in regard to the centrality of enslaved and plantation labor.3 Literary conventions and intellectual trends reinforced artistic representations of the British Caribbean as a less African and less brutally exploitative labor regime than it was. At the same time, the Enlightenment encouraged an aestheticization of work that elided slave labor and instead lauded the acumen of white planters and managers whose knowledge and expertise harnessed the natural bounty of the tropics. In representations of Britain and the Caribbean, agricultural peasants and the realities of the slave system were expunged by pastoral artists and writers.4 3 Grainger, The Sugar-Cane: A Poem. In Four Books. With Notes (London, 1764), 8 (quotation); Philip Wright, ed., Lady Nugent’s Journal of Her Residence in Jamaica from 1801 to 1805 (Mona, Jamaica, 2002), 10, 25–26. James Hakewill’s painting of the Whitney Estate in Clarendon Parish is a good example.

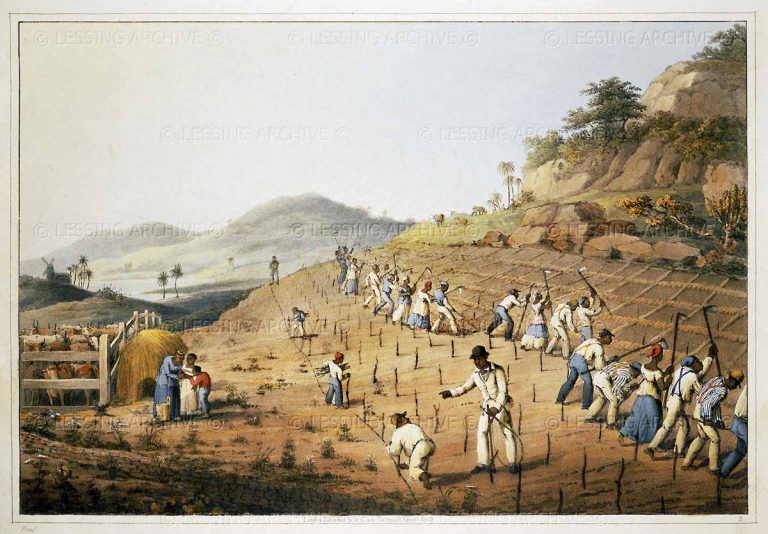

3Hakewill’s is a well-balanced artistic work, with the Mocho Mountains of south-central Jamaica defining a picturesque background while a crisp, white, and well-maintained stone wall and archway in the foreground invite the viewer into Viscount Dudley and Ward’s plantation. No more than ten people can be discerned, all black and well-dressed: these are not the members of the first, second, or grass gangs whose labors were so central to the plantation community. Extensive plantation buildings—the structures of sugar production, with the exception of a few slave houses on the right—dominate the center of the picture. The plantation landscape, then, appears well-ordered and lightly populated, simultaneously pastoral and implicitly semi-industrial, and very few of the three hundred or so enslaved people who populated and powered this successful estate can be seen. Those in evidence appear to be moving at a leisurely pace, and the only hard labor apparent in this bucolic scene is undertaken by oxen, while the only visible whip is in the hands of the enslaved man driving them. Late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century images of Jamaica and the British Caribbean rarely show enslaved people laboring to cultivate, harvest, and process sugarcane. Instead they are more commonly represented undertaking less arduous 4work, such as driving animals, marketing, or doing laundry, or at leisure in conversation, singing, and dancing.5

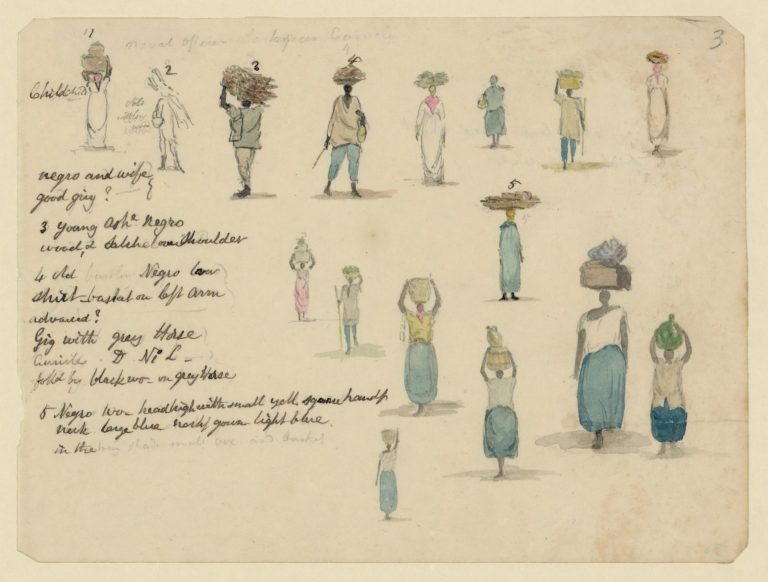

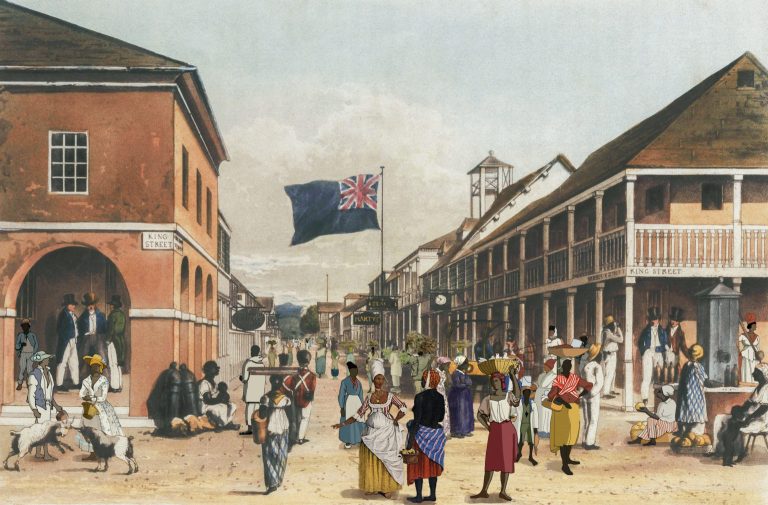

Artists did produce images of enslaved and free people of color as higglers and marketeers, partly because they were ubiquitous on Jamaican roads and in urban areas, but also partly because such pictures enabled the presentation of enslaved people—especially women—not as field slaves but rather as petty producers in familiar cultural and economic settings. Appearing well-dressed, content, and healthy, higglers, the free, enslaved, and runaway Jamaicans who traveled the island’s roads as vital agents of the internal marketing system, were represented in ways that echoed William Marshall Craig’s renderings of Georgian British hawkers for Richard Phillips’s Itinerant Traders of London. Thus these images presented the enslaved in ways that appeared familiar to British readers but that were a far cry from the actual plantation labor of the vast majority of black Jamaicans.6

5Even the artistic images that did show the enslaved engaged in field work were problematic. Consider William Clark’s representation of first gang enslaved men and women digging cane holes in Antigua.

William Clark, Holeing a Cane-Piece, from Ten Views in the Island of Antigua, in Which Are Represented the Process of Sugar Making, and the Employment of the Negroes . . . From Drawings Made by William Clark, during a Residence of Three Years in the West Indies (London, [1823]). Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, (for all JCB media).

Although Clark’s series was intended to accurately represent sugar agriculture and production, its target audience consisted of Britons, and the scenes were fanciful and idealized. Hoeing cane is incredibly arduous work, yet the enslaved in Clark’s picture do not appear unduly burdened. Working in the hot and humid climate of the late summer and early fall, these first gang workers exhibit no sweat stains. Indeed, the fact that they are all fully clothed is inaccurate, for most would have been wearing relatively little. The scars of whip marks might well have been evident on the backs of some, especially the four workers near the center of the line, who appear to be falling behind and who were liable to be whipped by a driver responsible for ensuring a steady and even rate of progress. A black driver is depicted in the foreground, but he has turned his back on the work of the first gang to direct the setting of markers, an unused whip at his side. To the left, an older woman provides water to a young boy, suggesting that rest and refreshment are easily available. In this artistic representation, we cannot really see the brutal, backbreaking work of the first gang that destroyed healthy young bodies in little more than 6a decade.7 The artwork of Hakewill, Clark, and others reveals how white Jamaicans and Britons chose to perceive and present Jamaica’s rural slave society. This article challenges readers to see and hear beyond these sources.

Images of Jamaican urban scenes are no more reliable than rural ones. When Hakewill sketched Kingston in 1820, the city was likely home to well over twenty-five thousand people, most of whom were enslaved or free people of color. These numbers were swelled by transient sailors and soldiers and by visitors from around the island and beyond. Hakewill presented the city’s widest and perhaps busiest street, just one block in from the piers and warehouses of Port Street, yet this painting imagines a sparsely populated scene of picturesque and well-maintained buildings, with a wide and largely empty street and intersection. Fewer than twenty Jamaicans can be seen clearly, half of them white and three of these British soldiers whose bright red jackets draw the viewer’s eye. The scene is genteel and as quiet as a small English market town, and the presence of a handful of black people, mostly women and children, barely hints that this was the cosmopolitan metropolis at the heart of Britain’s largest and most successful plantation slave society.

(4)

James Hakewill, Harbour Street, Kingston, in A Picturesque Tour of the Island of Jamaica, From Drawings Made in the Years 1820 and 1821 (London, 1825). Bridgeman Art Library. Additional artwork and video by Anthony King.

By contrast, this enhanced version of Hakewill’s quieted Kingston gives a sense of how Kingston was much more lively, crowded, and black than Hakewill’s idealized print suggests. By filling the urban scenes with 7representations of enslaved and free people of color based on paintings, prints, and sketches from the era, these enhanced images challenge the viewer’s unthinking assumptions about urban Jamaica based upon Hakewill’s presentation of fewer than twenty people—half of them white—in the heart of the city.8 But even a digitally enhanced version can only suggest so much. Kingston was more dirty, chaotic, and foul-smelling than this enhanced image reveals, with infirm and destitute people jostling with buyers and sellers of all manner of goods, white and black sailors, and others. Urban places could be overwhelming and even frightening for white people, and the cities’ soundscapes contributed mightily to their discomfort.9

The meaning and significance of sounds were shaped by the society and culture of those who heard them, and the aural landscape of eighteenth-century Jamaica helped define how inhabitants perceived and experienced their island home in ways that are scarcely comprehensible to us today. Indeed, Richard Cullen Rath has persuasively argued that during the early modern era sound had more import in relation to vision than is true today, and people “granted sound a power in which we no longer believe.” Conveying elements of the sensory experience of early modern Jamaica—albeit via recordings or representations created in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries—requires not just the ability to imagine how things sounded, smelled, or looked but, more significantly, a capacity to comprehend the elaborate social systems that governed the ways in which white and black Jamaicans processed and interpreted those sensory experiences.108(continued from page 7) 2001), 7; Peter Charles Hoffer, Sensory Worlds in Early America (Baltimore, 2003), 4–5, 14, 19, 133–50. A leading example of the use of recordings to present a historical aural landscape is Emily Thompson, The Roaring ’Twenties: An Interactive Exploration of the Historical Soundscape of New York City, designed by Scott Mahoy, produced through multimedia journal Vectors 4, no. 1 (Fall 2013), http://vectorsdev.usc.edu/NYCsound/777b.html.

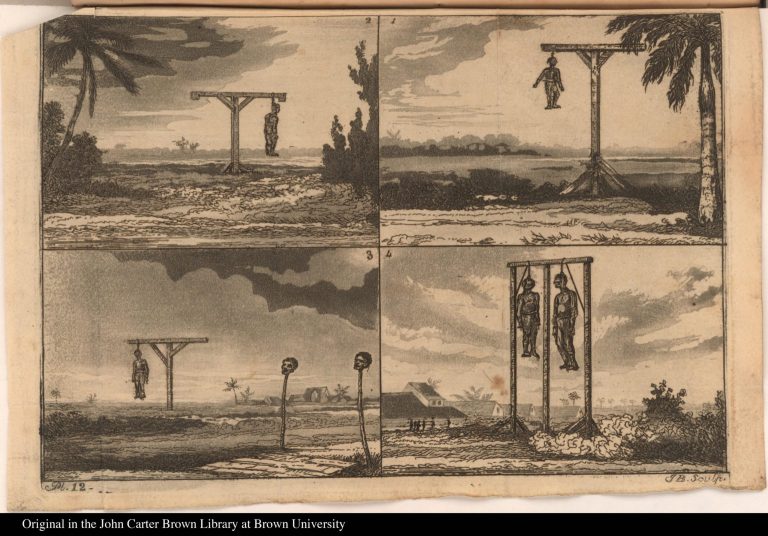

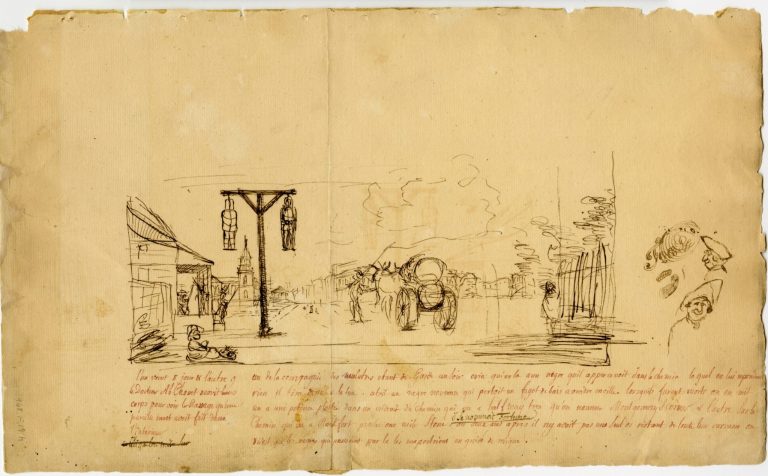

In order to help us imagine and comprehend the early modern Jamaican soundscape, this article uses traditional Jamaican music, much of it from mid-twentieth-century Smithsonian Folkways recordings. For example, “See Dem Gyal a Molain” is a “jawbone” piece performed by musicians from the Moore Town Maroons, recorded in 1977–78. As such it is a modern recording, but the Moore Town Maroons have been an independent and relatively self-contained community since the mid-eighteenth century, one in which Kromanti traditions and cultural forms, including the jawbone songs for recreational dancing, persisted well into the modern era. Though a recording such as this cannot be considered a precise rendition of eighteenth-century musical performances, it can nonetheless communicate a sense of West African-inflected soundscapes that both black and white Jamaicans might have heard at night as enslaved people gathered to eat, sing, and dance.11 Similarly, the digging song “Half a Whole” features a road-digging crew participating in a West African-inspired call-and-response song melded with harmonization stemming—at least in part—from British church music. Thus it represents a more modern and transcultural form that differs from the earlier and perhaps more explicitly West African call-and-response musical forms used by the enslaved on plantations. Yet though it cannot exactly reproduce the work songs of the eighteenth century, a recording such as this one builds from those songs and can thus communicate a sense of this soundscape’s elements.12 This article also features modern readings of eighteenth-century sources, using modern regional accents (from both the British Isles and West Africa). These cannot replicate the sounds of speech two hundred and fifty years ago, but given the relationship between—for example—the Lincolnshire and south Yorkshire accents of then and now, the recordings can 9convey a sense of accent and dialogue.13 At the same time, hearing (rather than reading) eighteenth-century sources while simultaneously seeing maps and images may trigger subtly yet significantly different perceptions and understandings as readers experience source materials aurally and visually. In addition, this article deploys video and sound recordings of the Coronation Market in Kingston, Jamaica, combining modern sounds and images with historical descriptions and visual representations of the island’s marketplaces in order to enhance readers’ sense of how Jamaicans experienced congested urban spaces. Eighteenth-century Jamaican markets drew on African practices in a creolized Caribbean context, and of course there are significant differences between these and present-day markets. The purpose of these video recordings is to convey an impression of an overwhelmingly black Caribbean urban environment in which eighteenth-century whites’ senses might be overloaded by sounds, colors, and smells, no matter what sanitized images from the time might have suggested. European visitors to slave-era Jamaica were both fascinated and horrified by markets that were populated and shaped by the enslaved and, to a lesser extent, free people of color. In juxtaposition with eighteenth- and nineteenth-century written and artistic representations of historical markets and urban scenes, these videos of a present-day market can encourage the reader to imagine a very different kind of urban scene than the inherently problematic early modern source materials would suggest. Thus modern video and sound recordings together with enhanced eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art and maps can enable readers to expand their sense of how the inhabitants of Jamaica’s slave society saw, heard, and experienced their environment. By giving the reader a sense of how Jamaica looked, sounded, and felt, this article will shed light on how enslaved people were able to escape and elude recapture for lengthy periods of time. Escape from slavery was both difficult and dangerous. Leaving the island was rarely an option, and the interior offered no sanctuary because the maroons were bound by treaty and liberally rewarded for capturing and returning runaways. The potential price of escape was plain to see, for the decaying heads and skulls of rebellious slaves were mounted on sharpened sticks and placed at crossroads or intersections all over the island. As Thomas Thistlewood’s diary entries make clear, white Jamaicans regarded the deployment of these grisly human 10remains as familiar and routine, but to the enslaved they must surely have served as a constant reminder of the potential fate awaiting those who resisted their bondage.14

Recording of excerpts from Diary of Thomas Thistlewood, read by Prof. Matthew Strickland, May 2017. Diary of Thomas Thistlewood, vol. 1, Fri., May 18, 1750, p. 300, http://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3472441, vol. 2, Wed., Oct. 9, 1751, p. 234, http://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3472449, both accessed Aug. 15, 2016, Thomas Thistlewood Papers, James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library. 11 15

Scholars have shown, often in chilling detail, the full extent of slave-holders’ attempts to terrorize the enslaved into compliance. Some of the enslaved did engage in minor resistance and occasionally rebellion, but resistance and escape were both difficult and dangerous.16

While relatively few enslaved Jamaicans attempted anything other than brief periods of petit marronage, as many as 2 percent of the enslaved at any given point were absent as longer-term or persistent runaways. Flight at that scale did not fundamentally threaten the slave system, but if in 1788 2 percent of Jamaica’s enslaved were absent, they would have numbered more than 4,500 runaways, a number almost equal to the island’s entire population of free people of color (4,829) and corresponding to more than one runaway per square mile.17 A database of one thousand runaways in Jamaica who eloped from 1775 to 1823 demonstrates that at least 67 (6.7 percent) of the runaways in this sample were absent for 12 months or longer, a further 68 (6.8 percent) for 6–12 months, and 135 (13.5 percent) for 1–6 months.1812 (continued from page 11) 1791; Gazette of Saint Jago de la Vega (Spanish Town), Feb. 22, 1781–Oct. 10, 1782; Royal Gazette (Kingston), Apr. 8, 1780–Dec. 29, 1781, Jan. 1, 1791–Jan. 12, 1792, Aug. 3–17, 1816, May 12–19, 1821, Feb. 9–Oct. 12, 1822, Mar. 8–Sept. 20, 1823. Length of time at liberty can be ascertained either from an advertiser stating how long a runaway had been free or by calculating the length of time between absconding and the final advertisement, which might appear many months later. However, some of the advertisements in this sample come at the end of a run, and for some there is no information available about how often they were repeated. Therefore the numbers of long-term absentees were probably higher.

Newspaper advertisements confirmed that each year some long-term runaways remained at large, gradually disappearing from plantation records and thus no longer recorded as runaways yet still present on the island as a cohort of long-term escapees. Checking each and every black person on the roads or around plantations and in towns was all but impossible, and Jamaican laws aimed against runaways voiced white aspiration rather than reality.19

How were runaways able to remain free for extended periods? Put simply, many hid themselves in plain sight, concealed amid Jamaica’s large population of enslaved people and free people of color. They took advantage of what whites did and did not see in the Jamaican social and physical landscape.

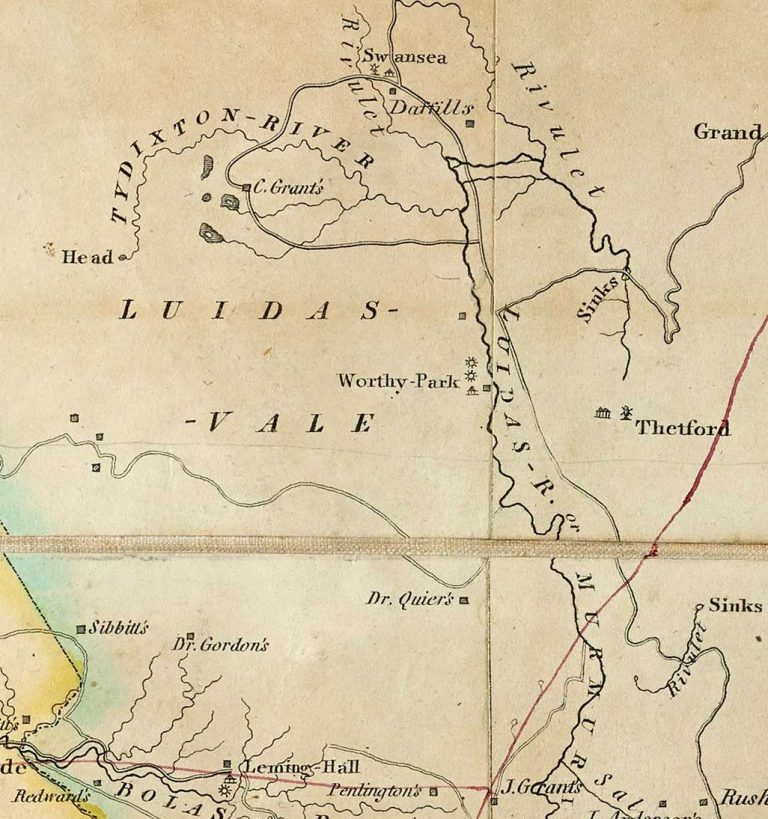

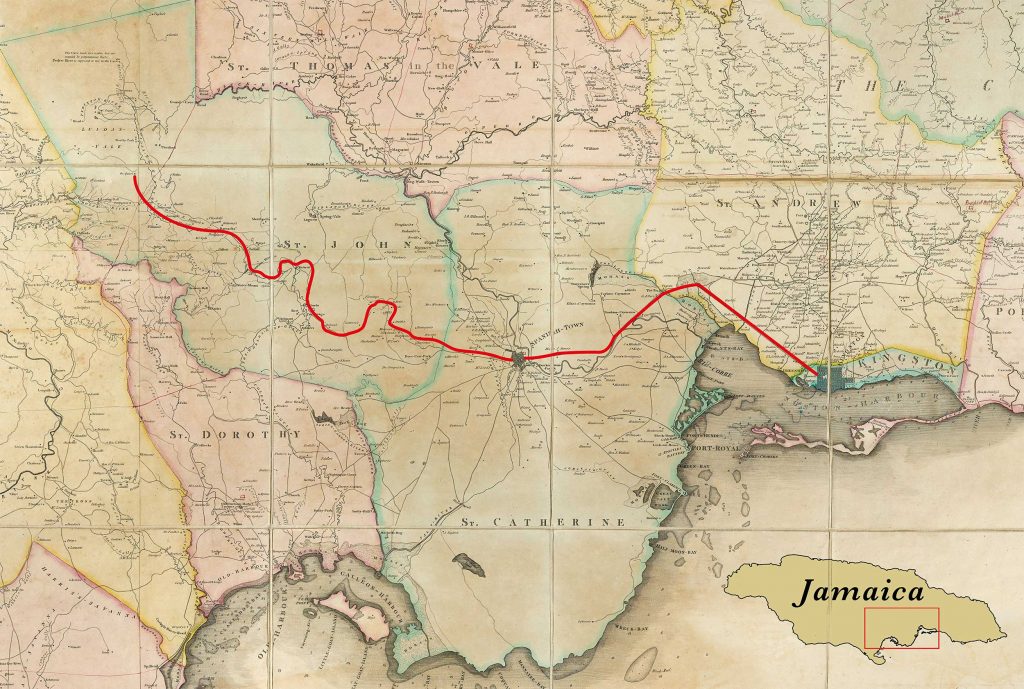

TO HELP ILLUMINATE A WHITE GAZE that might not see certain kinds of black freedom, this article will feature an imagined journey of a real person, Dr. John Quier, traveling from his home in Lluidas Vale, Saint John Parish, to Spanish Town and then on to Kingston in the early 1780s. A well-educated and highly regarded physician who treated white patients as well as the enslaved and free people of color, Quier lived in Lluidas Vale from his arrival in Jamaica in 1767 until his death in 1822. The article is not about Quier, but by imagining how white men like him perceived Jamaica and its people, we see more of the enslaved runaways who navigated toward long-term freedom.20

On a journey to Kingston, Quier would have seen a great many enslaved people and free people of color on and between plantations and pens, on 13roads and rivers, and working in towns and harbors, and among these were concealed runaways. Among all of the runaways referenced in the article, I shall focus in particular on about three dozen people who escaped from or were seen near locations on Quier’s route: approximately half of these escaped at or about the time of Quier’s journey, with others eloping in 1788 and 1791. (See 6.) These runaways will serve as examples of the enslaved Jamaicans who were sometimes able to remain at liberty in the heart of the plantation complex.21 14(continued from page 13) Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia, 2016). “The Carceral Landscape” is the title of Johnson’s chapter 8; see Johnson, River of Dark Dreams, 209. Reading traditional sources skeptically and using adaptations of primary sources, newly developed visual materials, and sources from the more recent past will enable us to move closer not just to an understanding of what whites saw but more crucially to a better sense of how enslaved Jamaicans— and especially those who sought long-term escape—were able to take advantage of what whites failed to see in order to remain at liberty in plain sight.

(6)

Map showing location of runaways along Quier’s route, with integrated runaway advertisements. Runaway icons are positioned adjacent to the places mentioned in the runaway advertisements. Click on the icons to reveal runaway advertisements. Map based on James Robertson, To His Royal Highness the Duke of York, This Map of the County of Middlesex, in the Island of Jamaica. . . . (London, 1804).; Robertson, To His Royal Highness the Duke of Clarence, This Map of the County of Surrey, in the Island of Jamaica. . . . (London, 1804). Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. Additional artwork, including stylized period effect runaway advertisements, created by Anthony King.

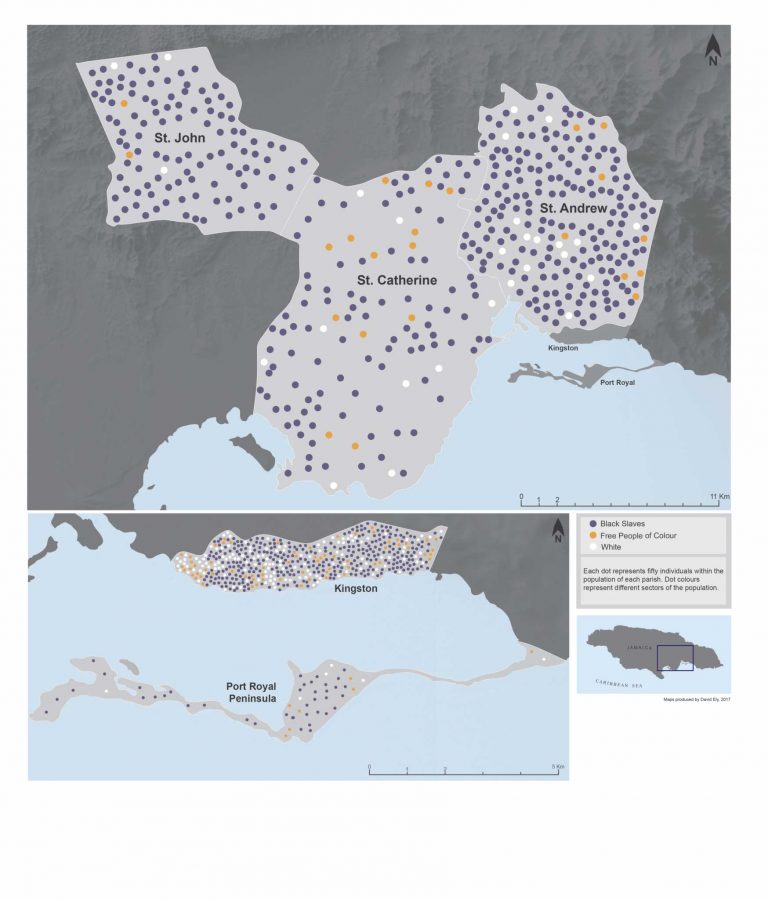

14Quier spent almost his entire adult life in an overwhelmingly black society. In 1788 Saint John, Saint Catherine, and Saint Andrew Parishes’ combined population of 1,411 white people and 1,191 free people of color was heavily outnumbered by 20,567 enslaved men, women, and children. After he reached Kingston’s thoroughly urban environs, the ratios were somewhat less imbalanced: 16,659 enslaved people lived and worked there among 6,539 white people and 3,280 free people of color. In 1788 there were approximately 226,400 enslaved people in Jamaica, and some 287,870 enslaved Africans had been brought to and forced to remain on the island during the preceding four decades. The constant arrival of Africans meant that creolization involved Africanization as much as if not more than Anglicization, albeit through the creation of a society and culture based upon quite varied West and West-Central African roots. There would have been many days when Quier saw few if any whites and when the voices he overheard were all speaking heavily accented English or West African languages. A present-day speaker of the Kromanti language, Isaac Bernard, gives a sense of at least some aspects of how eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Jamaican Kromanti may have sounded.2215

William Berryman, Old Harbour Market, Ponsie’s Tavern, Jamaica (1808–16). Library of Congress.

THE KROMANTI LANGUAGE OF THE JAMAICAN MAROONS

Recording of Isaac Bernard speaking a mixture of Akan-based Kromanti (Twi-Asante) and an archaic form of English-lexicon creole. “The Kromanti Language of the Jamaican Maroons,” recorded in September 2009 by Prof. Hubert Devonish and the Jamaican Language Unit, Department of Language, Linguistics and Philosophy, University of the West Indies, Mona, available at Caribbean Indigenous and Endangered Languages, http://www.caribbeanlanguages.org.jm/node/298. Used by permission of Prof. Devonish.23

Thus, while Quier might have sung or hummed the tunes and hymns of his native land, most of the singing he heard was African or creole, from nocturnal funeral assemblies to the digging songs of gangs of enslaved workers. It was black people, their sounds, and their activities that Quier would have seen and heard around his home and during his trip.16

Journeys through Jamaica and Jamaican slavery

(I) Lluidas Vale: forests, mountains, and plantations in Jamaica’s interior valleys

Quier’s journey to Kingston originated from Worthy Park Plantation in Lluidas Vale, Saint John Parish, which was not far from the geographic center of Jamaica. The terrain through which Quier would have passed is revealed by the following 3-D topographic video map.

(9)

3-D topographic video map showing Dr. John Quier’s imagined journey from Lluidas Vale to Kingston. Map by David Ely, based on Robertson, Map of the County of Middlesex; James Robertson, To His Royal Highness . . . This Map of the County of Surrey, in the Island of Jamaica. . . . (London, 1804). National Library of Scotland.

17In the 1780s Saint John was still quite sparsely populated and had fewer roads and settlements than more established parishes. Lluidas Vale was an interior valley, with a cultivated and fairly flat floor surrounded by densely wooded hills rising between 1,300 and 2,600 feet. Leaving the valley, Quier would have traveled south through sparsely settled hills that separated Lluidas Vale from Guanaboa Vale to the southeast, passing through forests with occasional pens and plantations. In Guanaboa Vale the terrain leveled out at approximately five hundred feet above sea level and Quier would have encountered more developed and densely populated areas. As he approached Spanish Town, Quier would have descended onto Jamaica’s southern coastal plain. From here all the way to Kingston, Quier’s journey would have been on relatively flat, heavily farmed, and densely populated land, often fifty or fewer feet above sea level, although there was a range of hills no more than a couple of miles to the north, with the Blue Mountains towering above the landscape ten or twenty miles to the northeast. The hinterlands of Spanish Town, Port Royal, and Kingston comprised the beating heart of plantation Jamaica, filled with people, agricultural activity, commerce, and the movement of people and goods.

In 1788 Quier’s parish of Saint John was home to only 178 white people (3 percent of the total population), who were heavily outnumbered by 5,650 enslaved people (95.5 percent) and 92 free people of color (1.5 percent). Around Quier’s house the population density was 1.5 white people and 48.1 enslaved people per square mile, so when he encountered the much higher 18density in Kingston—127.5 white people and 348.5 enslaved people per square mile—the urban environment must have seemed noisy, crowded, and rather more white than he was used to in the predominantly black society of Lluidas Vale. Quier never married, but he had relationships with enslaved women such as Dolly, Jenny, Susannah Price, and Catherine McKenzie, and at his death he left property to partners, children, and grandchildren. For Quier, creolization meant, among other things, his own incomplete assimilation into the African and creolized society of Jamaica’s enslaved.24

A map showing the racial population densities—as of 1788—in the areas of central and southern Jamaica that Quier would have passed through. Map by David Ely, based on Robertson, Map of the County of Middlesex; Robertson, Map of the County of Surrey. National Library of Scotland. The demographic data is drawn from “Return of the numbers of White Inhabitants Free People of Colour and Slaves in the Island of Jamaica,” November 1788, CO 137/87, 173, National Archives of the United Kingdom.

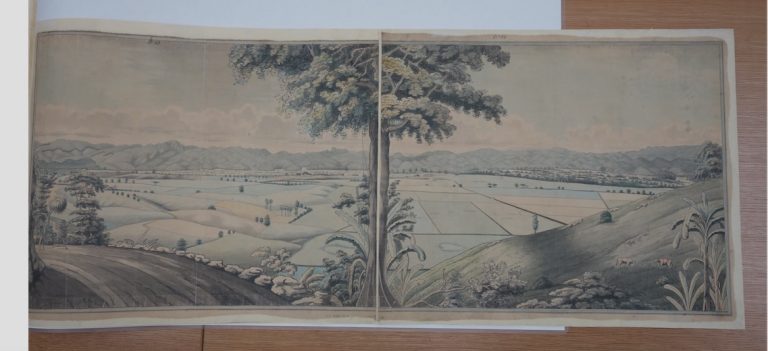

19Quier lived for more than half a century in Lluidas Vale, never once returning to Britain, and he tried to describe the beauty and attractions of his home in accordance with the literary conventions of his time. Writing for British readers, Quier portrayed a bountiful pastoral idyll, represented here by a watercolor of the area probably painted in the very early nineteenth century and a modern photograph taken from a similar vantage point.

RECORDING OF DR. JOHN QUIER’S DESCRIPTION OF LLUIDAS VALE

(12)

Unknown, Worthy Park in Lluidas Vale, watercolor painting, in bound folder of maps and paintings of Worthy Park, CO 441/4/4, 16, National Archives of the United Kingdom.

Photograph of Lluidas Vale by Marenka Thompson-Odlum, July 2017.

Recording of Dr. John Quier’s description of Lluidas Vale, from Quier to Dr. D. Monro, 1768, in Letters and Essays on The Small-Pox and Inoculation, The Measles, The Dry Belly-Ache, The Yellow, and Remitting, and Intermitting Fevers of the West Indies. . . . (London, 1778), xxvi–xxvii, read by Prof. Matthew Strickland, May.25

Despite his colonial fantasies, Quier would have been constantly reminded of the non-British character of the society he inhabited. Sometimes he might have been awakened at night by the sounds made by enslaved people gathering together in the wooded hills and mountains that surrounded Lluidas Vale, just as Thomas Thistlewood lamented in his diary in July 1750:

“Last night much Negroe musick, disturbed me.” “Music is a favourite diversion of the Negroes,” observed one white Jamaican, and Britons believed 20of their enslaved laborers that “notwithstanding their constant Labour, they would revel and dance five or six nights in a week, were they permitted.”26

SEE DEM GYAL A MOLAIN

(13)

Recording of a “jawbone” piece of music for dancing: “See Dem Gyal a Molain,” by Moore Town Maroons, track 6 on Drums of Defiance: Maroon Music from the Earliest Free Black Communities of Jamaica, recorded, compiled, and annotated by Kenneth Bilby, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings SFW40412, provided courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. © 1992. Used by permission.27

Having been in Jamaica for about fifteen years by the time of his trip, Quier might have had some sense of the African ethnicity of the music echoing around the darkened valley, which may have sounded something like this modern recording of a Jamaican “jawbone” piece. Yet recognizing such sounds was unlikely to make the music emanating from the darkness any more familiar or comforting.

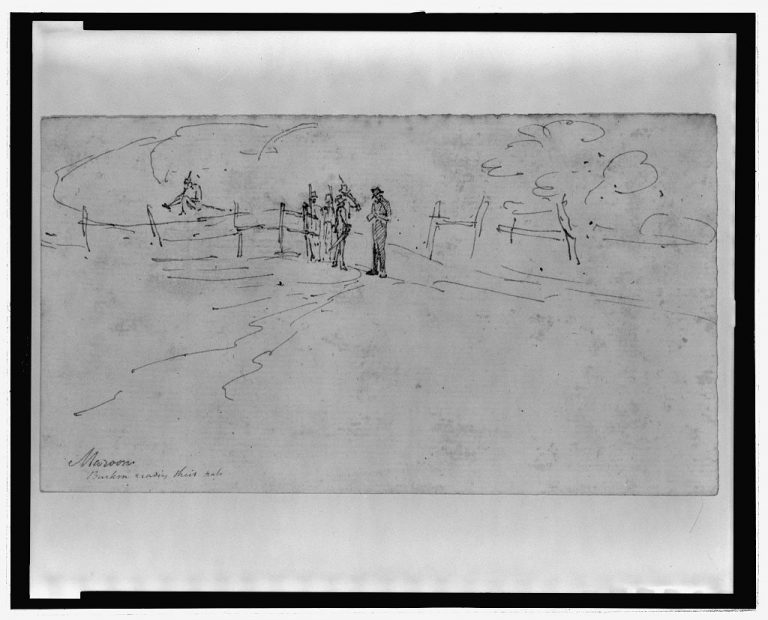

The sense of immersion in an alien culture would have been confirmed in myriad ways throughout Quier’s journey to Kingston. He would likely have departed soon after dawn, perhaps hearing “a large Cone Shell [that] is blown at Dawn of each Day, which can be heard at a considerable Distance, & immediately the Slaves repair from their Huts or Cabins to the Field of Work.”28 As he set off through Worthy Park, the plantation would have been coming to life: “every thing is in motion: the negroes are going to the field, the cattle are driving to pasture, the pigs and the poultry are pouring out from their hutches, the old women are preparing food on the lawn21 . . . and all seem to be going to their employments.”29 For the remainder of his journey, Quier would ride through and experience what he perceived as an exceptionally beautiful natural environment peopled by a large number of humans, mostly black and enslaved, engaged in a wide variety of tasks and occupations on plantations and pens, in towns, and on the roads that connected them. Many people used Jamaica’s roadways, most of them black and the majority of these enslaved. To be sure, Quier would have seen white people on the roads—planters and overseers visiting other plantations, soldiers and militia moving between posts, clerks and doctors conducting business—and many of those would have been accompanied by black people. Small groups of maroons also traveled the island’s roads with impunity, often bearing arms. Free people of color, many owning or working for small businesses, might travel in order to take goods and supplies home or to urban markets, or to visit friends and family.

Most of the people Quier would have encountered, however, were enslaved. He might hardly have noticed yet another middle-aged African-born woman, for the island’s roads were full of enslaved women carrying goods to and from neighboring plantations or further afield to towns and urban markets. Carrying messages and goods such as food and textiles, enslaved women trudged across Jamaica. Betty carried a large bundle of cloth, and her journey from a plantation a couple of miles east of Quier’s home may well have meant that she shared part of the doctor’s route to Spanish Town. Had they passed one another, Betty would likely have lowered her eyes deferentially and walked purposefully on, hoping to appear like the many other women authorized by masters to carry goods between plantations or to market. Or, given that Quier and Betty may have been in the forested areas surrounding Lluidas Vale, perhaps she would have simply taken cover when she heard Quier’s horse approaching, for she had in fact escaped from Stanhope’s Plantation near the head of the Black River. (See Betty/Stanhope on 6.) African-born and about thirty years of age, Betty bore the initials of her owner branded on her right shoulder. But because she looked like so many other enslaved women and men sent out on errands or to work as higglers, Betty blended into the island’s population and remained free for months.30

Enslaved people were regularly sent out on errands, carrying messages and goods back and forth, and thus were a constant presence on island roads. Thistlewood’s detailed diary records that he constantly sent and received all manner of items via enslaved women and men. 22

Recording of excerpts from Diary of Thomas Thistlewood, read by Prof. Matthew Strickland, May 2017. Diary of Thomas Thistlewood, vol. 21, Aug. 26, 1770, p. 142, http://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/4079831, vol. 29, Jan. 3, 25, 1778, pp. 7, 18, http://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/4079870, vol. 30, Mar. 9, Oct. 5, 1779, p. 38/163, http://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/4079876, all accessed Aug. 17, 2016.

Enslaved people provided communication between whites who often lived miles apart, and because much of this exchange was casual, local, and small-scale, it was informal and without proper documentation. While still in or close to Lluidas Vale, Quier might well have recognized many of the people he encountered on the road going about such business, but as he ventured farther from home he would have known few if any of the enslaved people he saw. Well used to sending and receiving messages and goods in this manner, he would likely have assumed that Betty and others like her were acting on the instructions of their masters.

Occasionally, runaways spotted on the roads were not taken up because it was unclear to observers that they had escaped. Four months after Quaw ran away, his master placed a new runaway advertisement for the creole man, stating that Quaw had been seen on the road by the Banbury Estate 23“on his way to the Magotty.” Toney, a “stout young Creole Negro Man . . .was seen by several Gentlemen” in the much-traveled Sixteen Mile Walk as the runaway made his way toward Spanish Town, yet he was not taken up. Also spotted on the Sixteen Mile Walk, some six months after his escape, was eighteen-year-old Caesar, who was seen carrying tobacco and therefore likely appeared to be going about legitimate business—as did a Coromantee named Roe, who had been at liberty for more than four months when he was twice seen on the road by the Barbican Estate, once “with a load of Pines, and at another time with Grass.”31

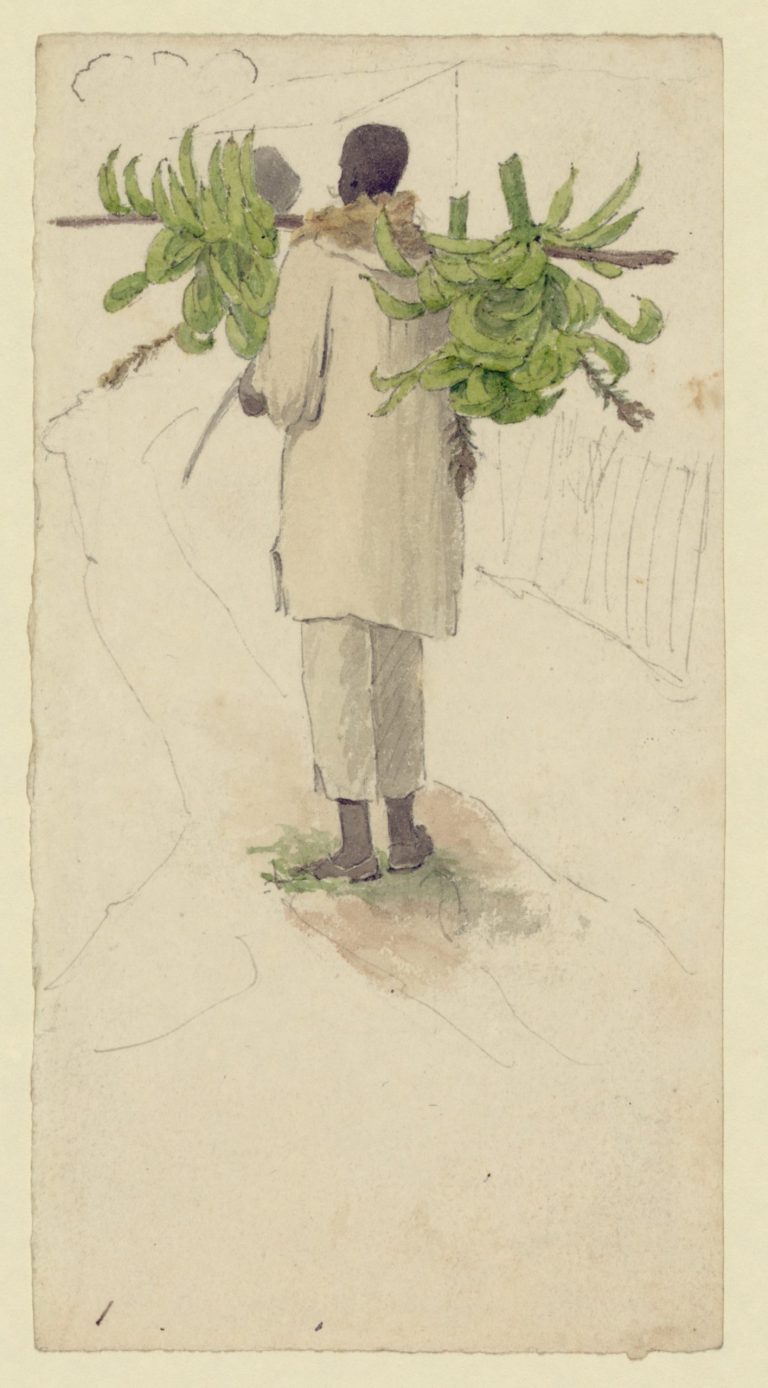

Quier and other white Jamaicans thus expected to see enslaved and free people of color on Jamaica’s roads. Foremost among these were the higglers. Moving between plantations and towns and between provision grounds and markets, they developed extensive knowledge of the island’s roadways. Some higglers were engaged in full-time commercial activity, while others undertook this as a secondary task beyond their usual plantation duties; the output from larger plantations sometimes warranted full-time higglers. Slave owners, especially urban white women and free women of color, found higgling to be a lucrative occupation for some of the people they owned.32 Higglers and people on the roads carrying produce were a popular subject for white artists, as shown by William Berryman’s portrayal of a man bearing plantains.

Like many such people on the Jamaican roads, this man is all but anonymous, his face unseen, and he and his labor are subsumed by the commodity he carries. In art and life, individuals faded into a world of linens, 24fruit, and other commodities, and on his journey to Kingston Quier would have seen hundreds of higglers who likely appeared to him as faceless purveyors of the foodstuffs and other goods consumed by white and black Jamaicans alike. The majority of higglers were women who found that it gave them a freedom of action and movement rivaled only by that of skilled male artisans permitted to hire themselves out. Small wonder that female runaways found higgling such an attractive option.33

Quier would surely have seen a great many higglers, among whom were concealed some runaways. In January 1791, for example, an advertisement for two enslaved women who had escaped noted that both were “used to higling” and thus were “well known almost all over the Island.” The first was Phillis, a forty-year-old Mundingo woman with “her country marks in her face” who eloped with her baby, Lucy. The second was another Mundingo higgler named Amy, who had escaped with a small child six months earlier and who was “well known about the island.” This advertisement was reprinted thirty-eight times over four months, after which Phillis and Amy may have been recaptured or their owner may have tired of the expense of advertising for them.34 Though masters and owners believed that enslaved people’s higgling meant that they would be well-known and recognizable— and thus vulnerable to recapture—it was also true that this activity gave enslaved people intimate knowledge of the island’s roads and plantations, a network of family and friends, and the expertise necessary to remain at liberty, providing for themselves and their families. Castile had been absent 25for nineteen months when her master advertised that “she is supposed to be higgling from Saltponds to Spanish Town,” a supposition that points to how higgling could provide long-term support for runaways, especially women. In fact higgling may well be the primary reason why women comprised almost one-quarter of runaways in Jamaica, a significantly higher proportion than in North America. Susanna had been gone for three years when she was highlighted in a runaway advertisement, but despite knowing that “she passes as an Higgler, and is supposed to be harboured about Golden-Valley or Mount-Pleasant, Blue Mountains,” her master struggled to recapture her. Such references to long-term runaways higgling were fairly common.35

Higglers were based in towns as well as the countryside, and the owners of urban runaways sometimes indicated that they believed escaped slaves might be in towns and on roads while engaged in this ubiquitous occupation. Nelly, a creole washerwoman and seamstress in Kingston, escaped from her owner in June 1790, and a year later he advertised that she “goes about higgling, frequently to Westward, and comes down to the Plantain Boats” to purchase fruit and then sell it around the island. Tom, a twenty-five-year-old Chamba with country marks, escaped from his Kingston owner in December 1791. Tom had previously worked in a canoe between Kingston and Port Royal but, since eloping, “is well known in Kingston of late as a higgler, and in Port-Royal where he is at present supposed to be harboured.” The fact that so many owners indicated in advertisements where runaways had been seen or were suspected to be higgling suggests that although whites and maroons might at any time challenge and take into custody anyone they suspected of crimes or of escaping, runaways were often working with relative impunity on the Jamaican roads that Quier traveled.36

(II) The road to Spanish Town: plantations from the limestone plateau to the coastal plains

As he left behind the forested high ground surrounding Lluidas Vale, Quier would have begun passing through a cluster of plantations and pens in the 26foothills between the Lluidas River and the Mountain River in Saint John. He would have seen hundreds of enslaved people working in plantation gangs, with smaller groups and individuals engaged in a wide range of activities. A short distance south of his route was Robert Dillon’s plantation, and if Quier had caught sight of one among many creole woman near the slave quarters, he would likely have assumed she was charged with food preparation, care of young children, or another plantation activity. But the woman might have been Fanny, enslaved by a Kingston attorney. (See Fanny/Dillon on 6.) Six weeks after her escape, the attorney advertised for Fanny, describing her as “sickly looking,” and he noted that her previous home had been at Dillon’s plantation, to which she might well have returned. Fanny would have known where to conceal herself on the plantation and when it was safe to walk around while drivers and overseers were occupied in the fields. Walking confidently between huts in the slave quarters occupied by her friends and family, Fanny would have looked at home. To passersby such as Quier, she would have been all but invisible, and a month later she may have still been free.37

As he drew closer to Spanish Town, Jamaica’s capital and second-largest town, Quier would have noticed increased traffic on the roads amid a more densely populated landscape. As well as enslaved people bearing goods and messages to and from Spanish Town, the roads often teemed with field workers and craftsmen. Carpenters, masons, and others walked bearing their tools, plantation hands made their way to different parts of plantations and provision grounds with hoes and bills, and other enslaved workers carried grass, animal feed, fish, and fowl. Quier likely saw a number of carpenters such as Andrew and Scotland, apparently walking toward their work with their tools or working on buildings on plantations and in towns, often under the supervision of white craftsmen. Andrew and Scotland had worked as enslaved carpenters in Kingston and Spanish Town respectively before being purchased by Bennett Smith and moved to a property just west of Spanish Town. The two men promptly escaped and likely moved around presenting themselves either as free men or as enslaved craftsmen authorized by their owners to hire themselves out. (See Andrew, Scotland, et al./Smith on 6.) They traveled a good distance: Smith believed Andrew had returned to Kingston, where he had formerly been enslaved, while Scotland had taken refuge in the mountains of Saint Catherine. Should Quier have encountered carpenters and craftsmen, he might have stopped and chatted with their white supervisor. If Andrew, Scotland, and other runaways were among the group, were they nervous? Even if they were, it was hardly unusual for enslaved men, women, and children to appear uneasy before white 27men. Apparently, Scotland was able to master such fears, for he remained at liberty for at least one year and perhaps longer. Working alongside other craftsmen and laborers repairing or constructing buildings, Scotland would have appeared to Quier and other white men to be exactly what he was: one of many skilled men working within Jamaica’s expanding economy.38

Perhaps not surprisingly, highly skilled and valuable plantation workers appear regularly in runaway advertisements. The elopements of carpenters, stone masons, sugar boilers, and the like were more likely to prompt their owners to advertise than were the elopements of field hands. Though some of these skilled workers may have abandoned their crafts, others—much to their owners’ chagrin—continued to do such jobs. African-born Titus and Peter were described by their master as, respectively, “a good boiler” and “an extraordinary good boiler.” Their value was enhanced by the fact that Titus “can turn his hand to almost anything on a sugar estate” while Peter was a “compleat sawyer.” The runaway advertisement describing them appeared nearly ten months after their elopement, and their master noted the men “took with them very good cloaths, and it is supposed pass for free people.” They had been seen on the Barrack Road in Westmoreland and on the road to Little Bogue in Saint James, and their owner thought it possible that they were traveling about the island hiring themselves out.39 Likewise, May was a plantation carpenter who eloped with four other people, including his wife, Lettice. It is possible that May had run away before, given that he was branded on both cheeks and one of his ears had been cropped, “which he endeavours to hide with a handkerchief.” The runaways were well known in Sixteen Mile Walk and Spanish Town, and their master “suspected there are white people privy to their being run away,” a frequent problem that enraged the owners of plantations near Quier’s path.40

Though Quier (and other white Jamaicans) would have encountered many enslaved people on the roads, he would have seen a great many more on and around the plantations and pens that he rode through and past. He might regularly have heard gangs of slaves singing “digging songs,” using the rhythm of call-and-response to regulate their work rate, and somewhat modernized versions of such songs have survived to the present, as is evident in this recording of “Half a Whole.” 28

(16)

“Digging Song: Half a Whole,” by field workers in Maryland, Saint Andrew’s Parish, track 4 from John Crow Say . . . : Jamaican Music of Faith, Work and Play, Folkways Records FW04228/FE 4228, provided courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. © 2004 Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/1981 Folkways Records. Used by permission.

Quier would have thought little of seeing black Jamaicans engaged in routine and familiar activities, but among this large and seemingly legitimately industrious population were concealed runaways. Many advertisements, in fact, indicated that runaways were likely sheltered on or near plantations by partners, family, friends, African “countrymen,” or Middle Passage shipmates.41

A stone’s throw from Quier’s route, a field hand named Cuffee, a wainman named Dick, and a waiting boy named Fortune escaped from Smith’s plantation outside Spanish Town at much the same time as the carpenters Andrew and Scotland, and they too were able to remain at liberty for some time. (See Andrew, Scotland, et al./Smith on 6.) Their owner thought that Cuffee and Dick were being harbored a few miles to the north in Saint Thomas in the Vale while Fortune was concealed closer by, in or around Governor’s Mountain in Saint Catherine. Probably dressed as field workers, both men were at risk when away from plantations, particularly if they ventured as far as Smith suspected: perhaps they carried goods with them so they would appear to men such as Quier to be on assignment for their masters, or perhaps they simply traveled at night. Advertisements for Smith’s runaways continued for about three months until he published a new one indicating that Cuffee, Scotland, Fortune, and Dick were still at liberty along with a driver named Quamina, Dick’s brother, who had escaped some time before. Unusually, this new advertisement indicated that Dick, Quamina, Scotland, and Cuffee “have been out a sufficient time to come under the law of the island to punish them with Death,” yet it balanced this threat with a promise to forgive any of these runaways who returned within the month. The reprinting of this advertisement for a further three months suggests that Smith’s combined threat of punishment and offer of forgiveness had failed.4229 (continued from page 28) November last,” Gazette of Saint Jago, May 3, 1781, 3. Dick, Scotland, and Fortune were listed in “Run Away from Bennett Smith,” Gazette of Saint Jago, July 5, 1781, 2, which was reprinted until at least Oct. 4, 1781. Dick, Cuffee, Scotland, Fortune, and Quamina were listed in a subsequent advertisement that appeared weekly from Oct. 11, 1781, to at least Jan. 3, 1782; “Run Away from Bennett Smith,” Gazette of Saint Jago, Oct. 11, 1781, 3.

29Their freedom was possible in part because of the complicity—whether intentional or not—of free people and whites who benefited from the labor or goods provided by runaways. Twelve-year-old John Coromantee was believed by his master to be harbored by “one Webly,” the overseer on a pen in the Walks. Bacchus, a thirteen-year-old Chamba boy, was “supposed to be harboured by a Mr. J.W.” Meanwhile, Dickey “was taken up, and harboured by one John Demerlin who lived upon Good Hope Estate”; allegedly, Dickey had abandoned plantation work and was now waiting on Demerlin as a personal servant. White complicity was on occasion directly in evidence, as when John William Harris left his post as bookkeeper on Eden Estate and “enticed away with him a Mulatto Boy named Henry Buckley, 16 years of age.”43

Enslaved Jamaicans might also harbor runaways, and this regularly happened following the death of a planter or pen owner. Though some properties passed quickly into the hands of a new owner with little disruption to the lives and families of the enslaved, others went into administration, resulting in the sale of land, equipment, and people. Whether from fear of such disruption or eagerness to take advantage of a relative vacuum in leadership, some enslaved people contrived to escape shortly after their masters died. George and Will, for example, escaped from Peter Ramsay’s plantation, which was immediately adjacent to Quier’s route along the road into Spanish Town. (See George and Will/Ramsay on 6.) It had been the work of seventeen-year-old George “to attend and wait on” the late Ramsay. He eloped at about the same time as Will, and for about four months he was able to remain free in Port Royal and Kingston. Several months later he escaped again.44

Following Ramsay’s death eighteen-year-old Will was allowed by Ramsay’s executor to hire himself out. The written permission he had from the executor enabled Will to move freely between his home, Spanish Town, Port 30Royal, and Kingston, and he might have been one of many such men and women seen on the roads by Quier and other white travelers. Will used this freedom of movement to escape. Had Quier stopped Will, the runaway might well have called upon the executor’s note to justify his presence on the roads or in town. According to a succession of advertisements, Will was regularly seen in and around Kingston and Port Royal, where he passed as free.45 He remained free for at least one month before being recaptured, but six months later he appeared in a new advertisement stating that he had once again escaped. This time he did not have permission to hire himself out, and the advertisement noted that he “is supposed to be harboured on board one of his Majesty’s ships of war at Port-Royal.” With a great many white sailors and soldiers succumbing to tropical diseases and Jamaica vulnerable to a Franco-Spanish invasion, recruiters were eager for any free black volunteers and may not have been particular about paperwork.46

As Quier got closer to Spanish Town and then the coast, he would have seen black and white seafarers and soldiers, and these might occasionally have included recent or longer-term escaped slaves such as Will. For example, a suspected runaway who “calls himself Jack Griffin” was taken up at one plantation “in company with two Sailors.” This advertisement does not make clear whether the sailors were white or black and, if the latter, whether they were free or enslaved. But given that enslaved men regularly worked both on smaller coastal and larger ocean-going vessels, it would not have been unusual to see such men in sailor’s garb traveling to and from their home towns and plantations.47

Either fear of punishment or actual punishment sometimes triggered escape. Just beyond the western outskirts of Spanish Town lay John Taws’s estate, from which August eloped despite being partially “lame” since birth. (See August/Taws on 6.) Escape was not new to August: twenty-three years of age, he had been newly branded with Taws’s initials “for a former defection and robbery.” Taws believed that August might have sought refuge with his uncle, an enslaved man in Kingston, or with two other runaways who accompanied him, both of whom had previously attempted to join the crews of Royal Navy vessels.48

31Large group elopements were unusual but did occur. At least thirteen enslaved people escaped from March’s plantation just west of Spanish Town. (See Jack Pot et al./March on 6.) Jack Pot, Carthagene, and Quaw were middle-aged or older men; Friendship was an older woman; Jemmy, Joe, Toby, Quamin, Dick, Quaw, and the “new Negro man” Sampson were all younger men; and Sanga and Sappho, a “new Negro woman” who had recently been branded with her master’s initials, were young women. The runaways may have escaped en masse but they would not have traveled together on the roads, and this group split and headed in different directions. March believed that two of them were harbored near or around the Caymanas, a few miles past Spanish Town and just north of Quier’s route to Kingston, while most of the others had been seen or were suspected to be harbored in or around either Spanish Town or Kingston. Even the recently arrived African named Sampson had been seen carrying wood into Kingston. Riding along the roads into and out of Spanish Town and Kingston, Quier would hardly have noticed him.49

(III) Spanish Town to Kingston: pens, plantations, and urban and seafaring workscapes on the coastal plains

Spanish Town would have been familiar to Quier as the seat of government and of island courts, yet he and most visitors regarded it as somewhat dilapidated and faded in comparison with the thriving and much-larger Kingston. The capital had “irregular and narrow” streets and buildings in varying states of disrepair, the majority of them inhabited by “free Negroes, Mulattoes, and slaves,” and white visitors were unimpressed by Spanish Town’s “air of gloom and melancholy.”50 Only the governmental buildings and open spaces at the town’s center hinted at the faded grandeur that led to James Hakewill’s imaginative representation, more evocative of Georgian England than Jamaica. Yet when the assembly and courts were not in session, there were even fewer white people in Spanish Town and it was easier for runaways to blend into an urban space dominated by enslaved black people and free people of color. This enhanced version of Hakewill’s image transforms the space by populating it with enslaved and free people of color and adding the sounds of a present-day Jamaican market. For all of the significant differences between then and now, modern sound recordings may still convey an auditory impression of the hustle and bustle of an overwhelmingly black urban space for commercial activity and socializing. 32

(17)

James Hakewill, King’s Square: St. Jago de la Vega, in A Picturesque Tour of the Island of Jamaica, from Drawings Made in the Years 1820 and 1821 (London, 1825). Bridgeman Art Library. Additional artwork and video by Anthony King.

Sound recording of Coronation Market, Kingston, Jamaica, recorded by Marenka Thompson-Odlum, July 2017.51

It was an easy ride along the coastal plain road from Spanish Town to the Ferry and on to Kingston. The road passed through an area “covered with sugar estates, penns, negro settlements, &c.,” and the countryside was far more developed and populous and far less wooded than Quier’s home area. Here, and indeed throughout his journey, Quier would have heard the loud crack of whips, for these were used not only to coerce or punish enslaved workers but also as signals to the enslaved, calling them to meals or back to work. Though this was “a sound particularly disagreeable to a stranger’s ear,” to resident whites such as Quier “it may be justly stated that it is mere noise.”52 Nowhere on Jamaica were the roads and countryside more crowded than here, and runaways did not hesitate to seek cover amid the throng. As Quier rode eastward out of Spanish Town, he would have seen many people such as Barbary, a young enslaved woman who had escaped from Chaloner Arcedekne’s estate just east of Spanish Town. The plantation was under the management of the planter and sugar magnate Simon Taylor, who believed 33that Barbary was seeking refuge in the capital with her aunt Bessy Byfield. No more than a mile from Arcedekne’s was Jacob Hill’s estate, and just a few months before Barbary’s escape Maria had eloped from Hill. African-born with country marks upon her face, Maria had Hill’s initials branded onto both of her shoulders. She had previously been owned by a Kingston merchant and might have made her way back to friends and a familiar way of life there, although Hill thought it more likely that she was living in the Red Hills, just north of Quier’s route from Spanish Town to Kingston. Hill believed that Maria was being harbored there by an enslaved man named Sharper, perhaps her partner. (See Barbary/Arcedekne and Maria/Hill on 6.) Enslaved women had much to fear from white men, but the crowds of people on the roads between Spanish Town and Kingston provided cover and protection.53

As he journeyed south and then east, Quier might well have seen some newly arrived Africans being led to the plantations and pens of their new masters by other enslaved people. After months of hellish incarceration on the West African coast and then in the bowels of slave ships, it is not surprising that some of these new arrivals seized their opportunity to escape. In the spring of 1780, for example, “A New Negro Man” ran away “on the Road, as he was conducting from Kingston, where he had been purchased about ten days before out of the Ann.” With no recorded name, age, or height, he could be identified only by the country markings on his temples, which were shared by thousands of African-born enslaved Jamaicans. Similarly, a young Eboe man who had apparently arrived on the ship Backhouse in July 1793 was “Lost” on his way to his new master’s property. Wearing no more than “a frock of very common oznaburgs,” he had begun the journey with a piece of card secured by ribbon around his neck bearing the name and address of his new owner.54 34

If newly arrived Africans were to elope and then remain free for any length of time, most would have done their best to get out of towns and to avoid white people such as Quier on the island’s roads. The densely populated large plantations in the Caymanas area that Quier passed as he drew close to the Ferry were both sources of and targets for newly arrived, creolized, and Jamaican-born runaways. A “new negro man of the Congo country” who gave his name as John was taken into custody on one of the Caymanas estates in February 1780. John claimed that he had eloped following the death of his master. Philip, on the other hand, was a “new Negro man, of the Mundingo country” who escaped from Taylor’s Caymanas estate. Bearing a branded mark on his right shoulder and “a good many country marks on his face,” Philip was supposed by his owner to have headed toward Liguanea or Above Rocks north of Kingston. Daphney had been on the island for much longer than John and Philip. She was an elderly African-born Papaw woman who had escaped from John Nicholson in Kingston and been free for almost a year. He believed that she was passing as a free woman named Mary Dennest and that she had found refuge with or near her husband, Quashie, who was an enslaved boiler at Ellis Caymanas. From there, Nicholson believed, Dennest regularly traversed the 35roads, perhaps passing as a free higgler. (See John/Caymanas, Philip/Taylor’s Caymanas, and Daphney/Ellis Caymanas on 6.)55

In addition to newly arrived Africans, many enslaved people were resold or moved between places of employment, resulting in constant traffic on the roads and opportunities to escape. Often masters’ first response to such elopements was to send other enslaved people out to search for the runaways. Thistlewood, for example, recorded in his diary that he sent Lincoln out in pursuit of runaways: “[Monday, July 2, and Tuesday, July 3, 1770] “Coobah runaway . . . Lincoln out looking [for] Coobah . . . [Monday, December 2, 1771] Lincoln out yet looking [for] Coobah, he has never Come home Since Thursday Morning, although Strictly Charged to Come home on Saturday Evening.” Given that masters tended to entrust “the most confidential people upon a plantation” with the pursuit of runaways, this strategy may have worked well, with those sent out in pursuit either forcing or persuading runaways to return. But the practice also provided some enslaved people with an opportunity either to escape or to pretend that they had been sent out by their owners in pursuit of other runaways. Thus, an advertisement for two runaways, Handel and Cuffy, described the latter as “a stout, young creole negro man” sent out “in quest of Handel, and has not returned.” Likewise, Tom had been absent for four months when his owner advertised for him as “a sensible fellow” who “pretends to be looking for a runaway Negro.” If Quier encountered a man named Sam on the roads near Spanish Town, the enslaved creole would have been able to produce written permission from Jacob Hill, who had sent Sam out in pursuit of a runaway named Preston. Quier would have had no reason to suspect that Sam had seized his opportunity and used the precious paper as cover for his own escape, making it easy for him to brazenly walk the island’s roads. (See Sam in pursuit of Maria/Hill on 6.)56

36With runaways escaping into the island’s population of enslaved and free people, masters often sought the assistance of enslaved people, hoping for information about runaways’ movements and destinations or even for their help in capturing those who had eloped. However, “it rarely happened that the slaves betrayed the confidence of a runaway, except he were base enough to rob their provision grounds, or insult their women; in either of these cases protection was withdrawn, and often, information given which led to his capture.” Had the island’s enslaved population actively supported masters in identifying and capturing runaways, far fewer escapees could have remained at liberty for extended periods. Escape and longer-term freedom depended upon networks of trust and complicity among the enslaved, despite the efforts of slaveholders to disrupt them.57

The presence on the roads of so many enslaved people sent out by their masters with letters, messages, and papers provided cover for some runaways. Jack, a fifteen- or sixteen-year-old “of the Congo country,” was sent by his master to Spanish Town in order to collect “some Papers of Consequence.” However, having received the papers, Jack seized his opportunity to elope, and his master was convinced that “as he may have such papers about him, he may expect to pass unmolested on that account.” Some tickets and passes were genuine but repurposed: Galloway, a thirty-five-year-old Coromantee enslaved man, had “a ticket to go to Kingston,” but his master had “forgot to limit the time of his returning,” which gave Galloway the opportunity to travel freely on the roads as he made his escape. Similarly, Polydore, an African-born carpenter and “a most artful villain,” made use “of a letter he received from the overseer at Stewart-Castle the time of his elopement, directed to ‘Mr. McGibbon at Windsor by Polydore.’” Polydore was adept at escaping and remaining free; four years earlier he had eloped for twenty months, during which time he had lived and worked in Kingston under the name John Brown. The letter provided Polydore with the opportunity to escape again. Edward, “a runaway cooper, belonging to Shrewsbury estate,” went to the owner of another plantation and asked for a paper to enable him to return to his master. However, once possessed of this pass, Edward “gave up all idea of returning to the estate . . . and whenever his proceedings were enquired into by the magistrates, he stated himself to be on the road to his trustee, and produced my letter as a proof of it.” Nineteen-year-old Dinah, who had escaped from an advertiser six months earlier, “informs any person meeting her that I have given her a ticket to work out, which is false.”5837per”); “Nightingale Grove Pen, St. Andrew’s, Jan. 26 1791. Ran away . . . Dinah,” Daily Advertiser, Jan. 27, 1791, 3 (“informs”). 37

Should Quier have bothered to challenge anyone like Jack, Dinah, or Polydore and inquired as to their business on the roads, he would likely have accepted the papers they carried as evidence that they were about their masters’ business. A seemingly legitimate document was a passport to travel freely on Jamaica’s roads: there were no official forms, simply small pieces of paper written by a wide range of people with varying skills, and so falsifying papers was not difficult for anyone who was literate. When Sarah Warren was taken up as a suspected runaway, she carried a manumission document that she eventually admitted was “written by her father John Warren, of Morant-Bay, for the purpose of passing her about free of molestation.” Warren’s father demonstrates how some whites and free people might choose to aid runaways: most likely a white man, he had been recorded a decade earlier as the owner of an African-born man named Bob who was branded with Warren’s initials and incarcerated in the Morant Bay Workhouse. Masters offered large rewards for evidence of such illegal activity, yet there are virtually no examples of successful prosecution of white abettors of enslaved runaways.59

The largest concentration of people on the road between Spanish Town and Kingston would have been at the Ferry, the primary hub on the road 38between the island’s two largest towns. There was an inn at the crossing of the Fresh or Ferry River, and most people traveling between the towns passed here. As such the Ferry was both a transit point and a destination for runaways. When Paul, a “horse ferrier or negro doctor,” escaped from Kingston, his owner indicated that Paul was likely “harboured about the Ferry.” Similarly, “a young negro” named Phebe escaped from the estate of her recently deceased owner, located just north of Spanish Town, and allegedly made her way to her partner’s “Grass Piece,” or hay field, near the Ferry. (See Paul/ Ferry and Phebe/Ferry on 6.) Like most whites on the island’s roads, Quier would have had neither the time nor the inclination to check the papers of each and every enslaved person he saw at busy hubs such as the Ferry. Moreover, Jamaican law provided exemptions from the standard restrictions on the public movement of enslaved people for those charged with “going, with firewood, grass, fruit, provisions, or small stock and other goods, which they may lawfully sell.”60

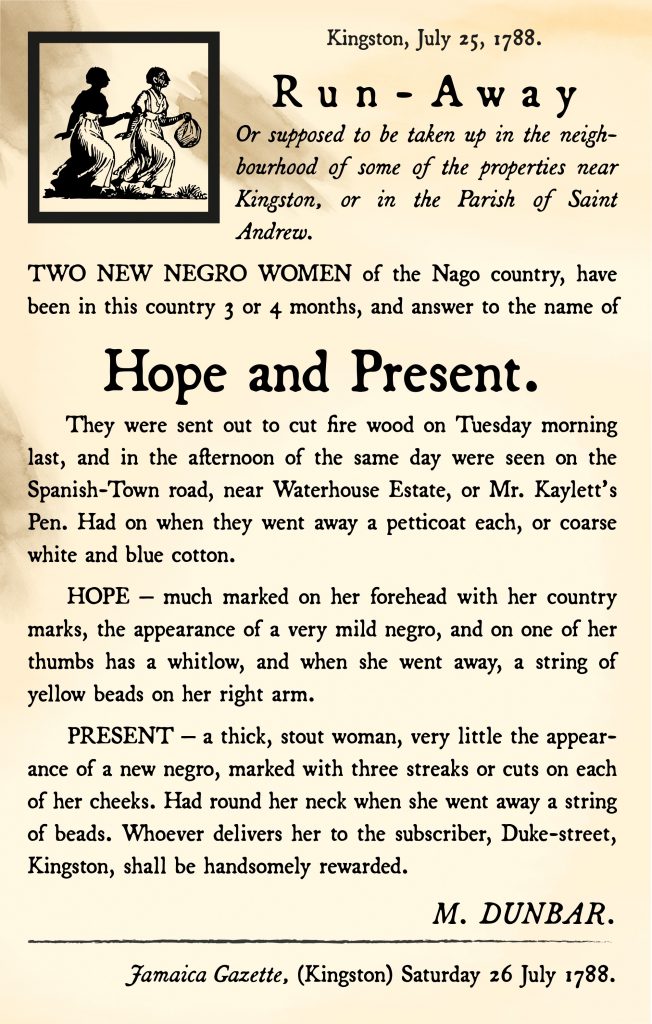

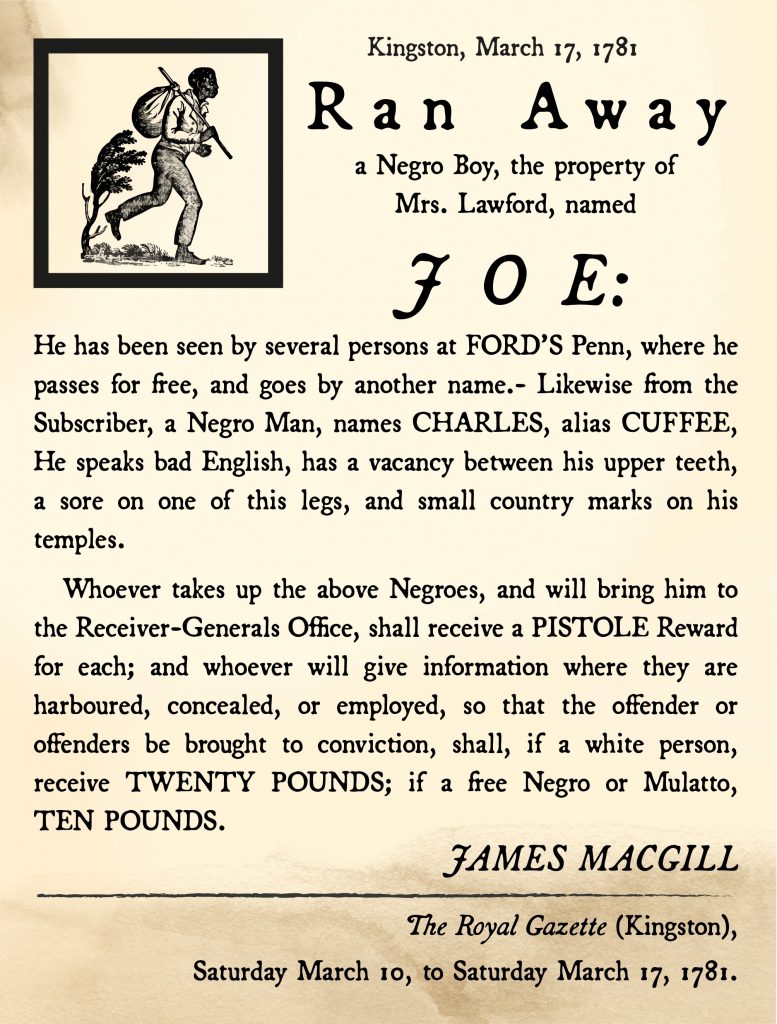

As Quier rode east from the Ferry toward the island’s most populous city, the roads grew even busier. Kingston was Jamaica’s largest market town as well as a financial and mercantile center, and it was the hub for free and enslaved people, white and black. The proximity of Port Royal, especially when a Royal Navy fleet was docked, and the presence of soldiers, sailors, and shore workers all made the area busier still. Each day thousands of people clogged the avenues into Kingston and Port Royal as well as the former’s major thoroughfares. Surely Quier would have seen quite a few people such as Hope and Present, two newly arrived Nago women with country marks on their faces, making their way westward out of Kingston to cut and gather firewood. The women had been in Jamaica only three or four months, but they seized their opportunity to escape. They were last seen on the Spanish Town road near Kaylet’s Pen. Out on this busy road they appeared to be two among many enslaved women carrying the firewood that Kingston needed, blending into the human scenery and counting on the fact that Quier and men like him did not notice them.61 Quier also passed by men, women, and children working on the pens that ringed the city, including Ford’s, Maxwell’s, Edwards’s, and Manby’s north of the Spanish Town road. With a mind full of the work and social engagements awaiting him in Kingston, Quier might barely have noticed someone like Joe, a boy who had escaped from Kingston and taken refuge at Ford’s Pen, “where he passes for free.” (See Hope and Present/Kaylet and Joe/Ford on 6.) And once Quier entered 39Kingston, the colors and sounds of the Jamaican countryside would have given way to the chaos and confusion of a bustling urban center of between two and three thousand buildings.62

(IV) Kingston

As he passed through the outskirts of Kingston and Port Royal, Quier’s attention likely shifted to the ever-closer waters of Hunt’s Bay and the Caribbean beyond.

Quier would have seen many more people and far more activity than is suggested by these images. The large ocean-going craft around and in Kingston and Port Royal harbors—and, if a naval fleet was present, a host of warships—would have dominated the ocean vista. Some runaways, almost all of them young and male, were able to take advantage of ship captains’ constant need for labor, and despite legal prohibitions and a system designed to prevent escape off the island, a few runaways were able to leave Jamaica rather than seeking to remain free of their masters while still living on the island.6340 (continued from page 39) 2 (“pass as a free man”). “An act to prevent the captains. . . . ,” Dec. 23, 1784, in The Laws of Jamaica: Comprehending All the Acts in Force, Passed between the First Year of the Reign of King George the Third, and the Thirty-Second Year of the Reign of King George the Third, Inclusive. . . . , 2d ed. (St. Jago de la Vega, Jamaica, 1802), 2: 356. White European sailors were always in evidence on Kingston’s larger 40 ships, but there were also black ocean-going sailors, some of them enslaved, such as Olaudah Equiano.64 Drawing closer to the water as Kingston’s harbor opened to his right, Quier witnessed a host of small craft, including fishing boats and droggers, ferrying people and goods around the island, as well as people working on or near the waterfront.

This would have been an almost entirely black scene, with virtually all small craft manned by enslaved men and free men of color, and as Quier drew closer to the ocean he would have been able to see and hear them more closely, along with all manner of dock laborers and ancillary workers such as sailmakers, riggers, and washerwomen. Again, however, artistic representations tend to privilege white men and marginalize if not eliminate the black population who dominated the bustling, crowded waterfront. And some of these people would have been long-term runaways. Will, a thirty-seven-year-old creole, was “a sailmaker by trade.” It seems likely that Will was used to hiring himself out, and, since he had been absent for three months, his owner suspected that the escapee was now working for himself. After Kent 41 eloped from a pen near Spanish Town, a runaway advertisement suggested that “he has been seen lately on the wharfs in Kingston, assisting the seamen,” while fourteen-year-old John “was seen at Port-Royal, in the King’s Yard, on Thursday and Friday last.”65

In and around Kingston, Quier would have seen many different groups of enslaved men, women, and children, along with smaller communities of free people of color, all providing potential refuge for runaways whose true status was hidden to whites such as Quier. The large community of fishermen was one such group. Johnny was “supposed to be harboured about the Bay by some of the fishermen,” and Edward was “supposed to be harboured by some of the fishermen at Old-Harbour.” Apollo’s master had utilized the enslaved man as a carpenter, but he was “also a good fisherman, at which business it is supposed he employs himself, as he has been seen lately at the east end of Kingston with fish.” Harry was one of a group of three enslaved men who escaped in July 1784, and when his master advertised for the runaways seven months later he reported that Harry “is frequently seen at Orange Cove fishing, and at Lucea Bay selling fish.”6642(continued from page 41) Apollo,” Jamaica Mercury, June 16, 1779, [issue of June 19, 1779, supplement, 94], in Chambers, “Runaway Slaves in Jamaica,” 1: 28 (“good fisherman”), UFDC; “Twenty Dollars Reward. Run away . . . Harry,” Cornwall Chronicle, Feb. 12, 1785, in Chambers, “Runaway Slaves in Jamaica,” 1: 102–3 (“Orange Cove,” 1: 103), UFDC.

42Women, too, might find work or refuge with partners in the dock and shore communities. Prue, “a creole Negro . . . with a downcast look,” was reported by her master to have been seen “in the King’s Yard at Port Royal, and is supposed to be harboured by the sailors or caulkers in said yard.” After Sukey eloped with her seamstress mother, Cuba, their owner reported that the young woman had “often been caught on board sundry vessels” in the Kingston and Port Royal harbor. Fanny had been absent for six weeks when her master advertised for her, announcing that she “has been seen several times at Port-Royal in the King’s Yard, with a Sailor’s Jacket on.”67

The militia, provincial troops, and British army regulars provided further opportunities for escaping slaves. There were both black and white soldiers in Spanish Town and in forts scattered all over the island, with a particularly heavy concentration around the harbor between Kingston and Port Royal. Their numbers were enhanced by the civilian auxiliaries who gathered around all early modern armies. These included many black people, such as Pioneers, enslaved workers hired out or conscripted to help with manual labor such as baggage carrying and construction, as well as free black and enslaved women who formed relationships with soldiers. Consequently, the communities of people associated with British military posts included many enslaved black people engaged in a variety of different tasks, and runaways could disappear into this large and chaotic scene. It was not surprising, therefore, that when Casandra escaped from her master in Kingston, he reported that she was “supposed to be harboured in or about Stoney Hill Barracks.” Similarly, Abba ran in the summer of 1790, and a year later her master advertised that she had “been lately seen at Stoney Hill Barracks, at which place it is supposed her husband is a pioneer.”68 Sixteen-year-old Brandom, better known as Brandy, had been “some time a waiting boy to an officer of the guards at New-York” before being brought to Jamaica and then sold. Brandy’s owner thought it likely that the young man preferred serving military officers to the lot of a typical enslaved Jamaican and that “he may attempt to impose on some gentlemen of the army here.”69

43Some enslaved men escaped in order to join the military themselves. James Baxter, a carpenter who “sometimes calls himself Alexander McCrea,” had been escaped for eleven years when he was retaken in 1779, having recently arrived in Spanish Town passing as a free man serving “as a soldier in the St. Ann’s Foot” militia. Once taken up, he was deployed as an enslaved carpenter on new defensive works around Kingston Harbor, but soon he escaped again. American-born John Russell “was formerly very fond of playing the fife, but has lately commenced preacher.” He had escaped once before and joined the Pioneers, and his master suspected that Russell “will attempt to pass as a free person . . . and may attempt to enlist into his Majesty’s service.” Similarly, a “creole Negro fellow” had already, his owner stated, “attempted to enlist in the new raised Corps, by the name of James Moore.” Jack, a twenty-year-old Congo escapee, did not just try to enlist. Despite having his owner’s initials branded upon his shoulder, he joined up under the name of John Murray and went “down to the Musquito-Shore” to participate in the British capture of Omoa from the Spanish in October 1779. Slave owners sought to regain runaways who joined the British military and to punish those who recruited or employed them, as when Captain Samuel Barton was convicted in May 1783 of “enlisting and detaining two negro slaves, the property of Mr. Henry Markall.” These runaways “had imposed themselves upon the defendant as free persons,” but because Barton had failed to identify them as runaways and then refused to surrender them to Markall, he was convicted and fined.70

With dusk falling there may have been more soldiers and sailors and fewer enslaved people associated with plantations on the road, but Quier might still have witnessed a funeral taking place in the “Negro Burying Ground,” which was located on the western edge of Kingston, a couple of blocks south of the road. 44

(23)

Map of Kingston in ca. 1745. Mich[ael] Hay, To His Excellency Edward Trelawny Esqr . . . This Plan of Kingston is Humbly Dedicated. . . . (Kingston, [1745?]). Library of Congress.

Although the enslaved may well have moderated their funerary practices because of the proximity of whites, the sights and sounds of the ceremony would nonetheless have struck Quier as being rather more African than European. A decade earlier, Equiano had witnessed such a ceremony, most likely in the Kingston burial yard, noting that the enslaved “still retain most of their native customs: they bury their dead, and put victuals, pipes and tobacco, and other things, in the grave with the corps, in the same manner as in Africa.” And then a decade after Quier’s journey, William Beckford reported that “when the body is carried to the grave, they accompany the procession with a song; and when the earth is scattered over it, they send forth a shrill and noisy howl, which is no sooner re-ecchoed, in some cases, than forgotten.” Following interment in the grave, “the face of sorrow becomes at once the emblem of joy. The instruments resound, the dancers are prepared; the day sets in cheerfulness, and the night resounds with the chorus of contentment.”71