About This Project

This digital humanities project is a companion to Voices of the Enslaved: Love, Labor, and Longing in French Louisiana.

Introduction

IntroductionThis project offers unparalleled access to voices of enslaved individuals in colonial North America. It is anchored by four complete trials from eighteenth-century French Louisiana in which enslaved deponents testified in court. Located within the Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana, these four trials belong to an archive of more than eighty trials dating from 1723 to 1769 that preserve the voices of close to 150 enslaved Africans and a handful of enslaved Native Americans who testified as defendants, witnesses, and, more rarely, victims. The deponents included men, women, elders, and even children. In conformity with French legal procedure, those who testified could answer expansively, and as they spoke, their words were written down and made a part of the court record.

The resulting repository of testimony is astoundingly rich and unique in scope among colonial North American archives in allowing the enslaved themselves to let us hear their thoughts and their pronouncements. Their access to testimony enabled them to construct a narrative that was rooted in their own experience and ways of knowing, one that was autobiographical because it expressed how they looked at the world, evaluated it, and made sense of it. These documents ring with the sound of their voices and their concerns, offering precious glimpses into real lives lived under the weight of slavery in all its endless cruelty and violence, voices of real people who seldom passed up an opportunity to insist on their humanity.

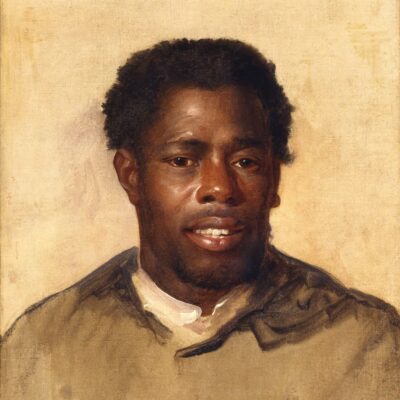

The trials selected for inclusion introduce us to four individuals, ranging from an elderly man to an eleven-year-old girl. In 1748, we find Jannot, an enslaved runaway tricked into returning to his master so that he could be forced to testify in a murder investigation. When prosecutors probed him about Voudou practices, he chose to pivot the questioning toward the violence that his wife experienced at the hands of her mistress. In 1764, we discover Marguerite. Accused of being a runaway, she spoke instead of her outrage at the way she was treated and locked up. Also in 1764, we have another runaway, the elderly Jeanot, who described the community support he received when his master stopped providing him with food and clothing. Lastly, in 1765, we encounter twelve-year-old Babette, who sought a brief reprieve from her harsh life with treats and apparel purchased with money she found in a chest left unlocked by her master. Their testimony, in all its abundant detail, offers rare, and often moving, information, but interpreting it is not without its challenges, not least in terms of how to untangle the meaning of their words. The task is magnified given the power imbalance inherent when the testimony is that of enslaved persons within a legal system stacked against them, which is also why it is crucial to present the trials in their entirety, including judicial and procedural documents that gave shape to the proceedings even if they do not always contain testimony per se. Hence, all of the documents related to the four trial records are presented here, from the manuscript pages themselves to transcriptions of the text into French to translations of the transcriptions into English, along with an introduction to each court case and to the individual at its center. Also provided is a detailed overview of court procedure. Although the commentaries aim to point readers toward salient aspects of the testimonies, above all, the goal of this project is to be interactive: it is an invitation to readers to engage with the primary documents, to seek to draw their own interpretations, and to explore the themes that they see arising from the texts.

The Archive

The ArchiveThe challenge of accessing the voices of the enslaved in colonial North America has long seemed insurmountable, based on the assumption that few such records were produced. It is “history’s cruel irony” as Annette Gordon-Reed has underlined, that “the individuals who bore the brunt of the system—the enslaved—lived under a shroud of enforced anonymity. The vast majority could neither read nor write, and they therefore left behind no documents, which are the lifeblood of the historian’s craft.” In French colonies, no formal prohibitions existed barring slaves from reading or writing, but not many possessed these skills, meaning that few written sources were produced by the enslaved. The problem of source material from enslaved individuals is seen as especially acute in the period before the rise of autobiographical slave narratives, starting with that of Olaudah Equiano in 1789. These published sources offer richly textured firsthand accounts of the life stories of individual slaves that showcase their voices, even when mediated by an editor or amanuensis. As a literary genre that emerged from Anglo-American Protestant abolitionist movements, however, autobiographies of the enslaved emphasized a trope of personal redemption that did not resonate with French or Catholic antislavery advocates, and no such narratives were created in France or her colonies.1

The evidence from French judicial slave testimony more than mitigates this void, offering an alternative set of historical voices and life stories that holds the potential to expand the canon of what we consider slave narratives. As outlined in the introduction to court procedure, French colonial law allowed the enslaved to testify in court in certain circumstances, as defendants, witnesses, and victims. It also permitted them in theory to speak as much as they wanted in their testimony and further required that their depositions be meticulously recorded. This was thanks to a distinctive feature of French law that hinged on testimony as central to judicial procedure. In particular, it privileged confession as the ultimate proof, since only the defendant was deemed to know the truth.

As a result, criminal trials in France and French colonies were subject to precise rules and strict guidelines to ensure the careful recording of proceedings. Clerks aimed for immediacy in writing down testimony, their goal to produce a faithful written version of what a deponent said. Answers that defendants and witnesses provided during questioning and the written documents that resulted from this testimony are comprehensive. Depositions are far more detailed, for example, than those of English colonial courts, where, in any case, the testimony of the enslaved was not always permitted. Even when such testimony was allowed, English law did not, as in French law, require a full and accurate rendering of court testimony, so there is no comparable archival body of evidence for the thirteen English colonies.

Though testimony by enslaved individuals in French colonial courts was not intended to serve as an autobiographical text, and though the depositions do not meet standard definitions of autobiography since they contain fragmentary detail rather than whole life stories, these records are nonetheless valuable and evocative. Thanks to Louisiana’s archives, which encompass testimony but also a multitude of other sources that can help us track the biographies of those who testified, the fragments are often enough to bring these lives back to the surface, even when we have only snapshots to work from. As narratives overflowing with personality, character, subjectivity, and humanity, they, too, offer voices of African and African-descended individuals, and more rarely, of enslaved Native Americans. The lives of these deponents bear writing about, and their lives must be thought about, not least because their own words help us do so.

Voices - Speech

Voices – SpeechThe trial records presented here, and the larger archive to which they belong, were not written down by the enslaved. They began as speech, oral expressions whose afterlife was in written form. In this respect, they offer a parallel of sorts to the first-person, oral accounts transcribed and edited in the 1930s as part of the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration, though they precede those narratives by two hundred years. Given this original form as speech, the evidence present in the French colonial court testimony of enslaved individuals rebuts the privileging of the written over the spoken word, as seen when Marisa Fuentes highlights “sources written by enslaved people themselves” as the default model for capturing “the limited voices of the enslaved.” In contrast, courtroom testimony began as an act of speaking prompted by an interrogation, with the goal of being heard by judges. The resulting written record reflected the ad hoc and ad lib nature of this oral speech, with passages punctuated by dialogue, colloquialisms, metaphors, figures of speech, and even Creole.2

Analyzing speech given in court therefore requires us to recognize that, though deponents could have planned what to say, the act of speaking is first and foremost a spontaneous performance that happens on the fly, shifting course along the way. As such, speech is also impulsive, subject to different rules and imperatives (not least the effect of adrenaline) than written autobiographical narratives, since it happens in the moment, without knowing ahead of time what questions would be asked or what a prosecutor had uncovered during his investigation. Depositions were acts of recall and of memory, which means that they could also lend themselves as forms of storytelling. As Ibrahima Seck suggests, for the enslaved in Louisiana, telling stories “eased the pain in their limbs and minds and allowed many to deal with their fate instead of crying or drowning in homesickness. Storytelling was also a means for the oppressed to create fictional situations where the weak could overcome the domination of the powerful,” sometimes using humor, including trickster tales. In their narratives, it was deponents who controlled what to reply in answer to questions. So, although they could not speak entirely freely, and their answers might put them in jeopardy, the evidence indicates that many found in the act of testifying motivations other than a single-minded focus on pure self-preservation, and in heeding their words and interpreting them, we must honor their complexity as sentient beings. To hear the testimony of one deponent, spoken in the original French with an English translation by a Louisiana French speaker, see Tiffany Guillory Thomas’s interpretation of the words of Marguerite.3

Certainly, testimony cannot tell us beyond any doubt whether the events described took place. But perhaps it matters more to understand how an event was narrated. For even when a court appearance was coerced or coached, there was room for redirecting the narrative away from the crimes being investigated—the clerk explicitly acknowledged as much when recording what one slave witness “said, without being asked” and then “said, again without his being asked” or what yet another slave defendant in a different trial “said, on her own initiative.” If not all enslaved deponents who appeared before the court in Louisiana were particularly forthright or expressive, they did go on tangents, veering off subject and offering details that seem irrelevant at first glance but are, in fact, deeply revealing and very often riveting. And when they did, in place of straightforward answers to questions posed about the court case, they instead offered hints about their worldviews and gave insights into who they were. In other words, appearing before the court provided individuals with an unexpected opportunity to narrate their own stories, to digress, to redirect questioning, and to introduce unrelated matters in an arena where, commanding full attention, they had to be heard.4

Jannot, Marguerite, Jeanot, Babette

Jannot, Marguerite, Jeanot, BabetteThis project is centered on four complete trials that foreground the testimony of four enslaved individuals—Jannot, Marguerite, Jeanot, and Babette—along with the testimony of many others. Yet we must also acknowledge the majority for whom there is no evidence. Saidiya Hartman has insisted on the problem of source material and the silence of the archives, writing about the emblematic figure of the enslaved woman in the Atlantic world that “no one remembered her name or recorded the things she said, or observed that she refused to say anything at all. . . . We stumble upon her in exorbitant circumstances that yield no picture of the everyday life, no pathway to her thoughts. . . . We only know what can be extrapolated from an analysis of the ledger or borrowed from the world of her captors and masters and applied to her.” This project aims to nuance that view and show that there are archives—problematic archives, certainly—which do allow us to encounter enslaved women and men speaking, and having their words recorded. In their interrogatories, they sometimes found ways to dodge questions, and they sometimes amplified their answers by veering to other subjects; but through it all, we hear their voices, and we find a pathway to their thoughts, even as we acknowledge that there is no ideal or complete archive, nor do we have the luxury to imagine one.5

The records of trials in which the enslaved testify are far from perfect, and their voices are never perfectly free, yet this archive enables us to perceive a space where the enslaved narrated their own stories, with immediacy, with urgency. Over and over again, the deponents found ways to implicitly condemn a system that sought to reduce them to chattel. Their courtroom narratives tell us that much, and yet so very much more, for they lift these individuals from anonymity, even as their stories foreground the heart-wrenching weight and cruelty of slavery.

In bringing to the surface their character and personality, and at times their emotions, inner thoughts, and intimate worlds, the individuals who testified rebutted slavery’s intent to silence them, to dehumanize them, and to render them anonymous. Mostly, we only catch sight of these individuals for brief moments in time. Yet here were real people who lived full lives. We are richer for having encountered them, however fleetingly. And whenever they did have the opportunity to speak and have their words recorded, we surely owe it to them to listen and to try to hear.

About The Author

Sophie White is Professor of American Studies at the University of Notre Dame, where she specializes in early American studies, with an interdisciplinary focus on cultural encounters between Europeans, Africans, and Native Americans and a commitment to Atlantic and global research perspectives. She hails from Mauritius and is a native speaker of French and of Mauritian Creole. White is the author of two books and more than twenty articles and essays. She is also co-editor of a volume on slave testimony in French and British America. She is a founding member of the Keywords for Black Louisiana DH Editorial Research Team (https://www.lifexcode.org/keywordsblackla). Her most recent book, Voices of the Enslaved: Love, Labor, and Longing in French Louisiana (Voices of the Enslaved | Sophie White | University of North Carolina Press (uncpress.org), has won seven book prizes, including the 2020 American Historical Association’s James A. Rawley Prize and the 2020 Frederick Douglass Book Prize for the best book on slavery.

Acknowledgments

I am truly indebted in such manifold ways to the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, with particular thanks to Cathy Kelly for sharing my vision for this digital project, along with Martha Howard, Emily Suth, and Nicholas Popper. The end product would be far poorer without the many interlocutors with whom I discussed the project, the contributions of my copyeditor extraordinaire, Kaylan Stevenson, the invaluable editorial assistance of Alexander Taft and Frances Bell, and the expertise of Scott Hale and the digital team at Colour Outside. Tiffany Thomas made Marguerite’s testimony come alive with her sensitive interpretation of the text. My profuse thanks go also to the peer reviewers, Celia Naylor and Randy Sparks, for their generous comments and feedback. The research on this source material began while working on Voices of the Enslaved on a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship, and I gratefully acknowledge their foundational sponsorship, as well as that of the Leverhulme Trust (UK). With all my love and gratitude, I thank Cleome, Josephine, and Simon for their presence in my life. This project is dedicated to my late father, Peter White, who, at his best, modeled a special kind of respect for people of all walks of life, always displaying a genuine curiosity about their lives and their thoughts.