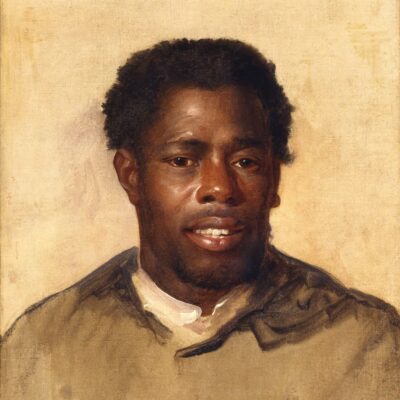

Jannot, 1743

An enslaved witness highlights his protectiveness towards his wife while corroborating the existence of Voudou ceremonies

Links

LinksLink 1: Elizabeth Clark Neidenbach, “Refugee Revolution: Covering the Crisis That More Than Doubled New Orleans’s Population,” 64 Parishes (Summer 2020), https://64parishes.org/refugee-revolution

Link 2: Jeannot, 1764, Commentary

Link 3: Dinah Eastop, “Material Culture in Action: Conserving Garments Deliberately Concealed within Buildings,” Anais do museu Paulista: História e cultura material, XV, no. 1 (January–June 2007), 187–204, https://www.scielo.br/j/anaismp/a/QrCC5nWC55GNBg77chTwfCJ/?lang=en

Link 4: https://youtu.be/a8qgcqqbZG0

Letter from Widow Corbin to Jean-Baptiste Raguet on the Disappearance of Her Son (Lettre de la veuve Corbin à Jean-Baptise Raguet sur la disparition de son fils)

Transcription

Letter from Widow Corbin to Jean-Baptiste Raguet on the Disappearance of Her Son[page 1]

(30600)

Monsieur

La mort de mon fils se presante dans

mon esprit en temps de diferante

fason que je ne puis man pechez de

vous en entretenir et [de vous] marques

Les enquetude quelle me donne depuis

vostre depar je me suis informé sy

Lon voyet des oyaux de prois autour

des deser on ma dit que non ce qui

est dautemps suprenent [sic] que ce pauvre

garson ne doit pas avoir disparue

je ne plus apresant dans Lides que

ce quoquin de ponpé a mr chatant Lau

roit tué ce qui me confirme dans

ce santiment est que La premiere

nuit que mon fils a manqué on a

enlevé unne voiture au debarquemen[t]

de nivet et que mon fils a arété

[page 2]

(30601)

plusieurs fois ce quoquin je croit qu[e]

Lon ne asarderoit pas baucoup a arete[r]

ce drole et aluy donner La que[s]tion

il ne doit pas esttre eloigné il etoit che[z]

mr fleuriot a la dance Lon ne peut me tirer

de le[s]prit a presant que Lon ne trouve

rien que [ill.] sil ne été tué car il

nest pas croiable qun homme dispar[ait]

de la fason dont il a fait sy ne Luy est

arivé de parre[i]l malheur que ceux que

je me figure je croit que Lon ne doit

pas negliger a punir ce quoquin sil

Lon peut decrouvrir qui soit coupable

il peut en vouloir a mon fils par que La

derniere foit qui Le pris il dit a son

petit frere qui Le conduiset chez m

chaperon que sil vouloit sanfuir de

tirer surluy ce que pierot fils son

[page 3]

(30602)

fusis netoit chargé avec du cel pou[r]

Luy faire peur et Lautre foit que

Lavoit pris il Lavoit fait foiter je

tout Lieux de le sousonner car ces un

tres mauvais suget vostre epouse

ce porte bien elle vous salue

je lhonneur destre tres parfaitement

Monsieur

Vostre tres hum[ble]

et tres aubeisan[te]

servante veuve

Ce 26e. juin 1743 baschemin

[page 4]1

A Monsieur

Monsieur Raguet

A La nouvelle orleans

on a tire coup de fusil le soir [ill.]

ont [ill.] la guildive

presents made bachemin [ill.] petit Jean Leveillé

barre La fers [ill.] his [wife?] his daughter Lafleur to [baulne] [ill.]

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/06/26/01 (day/month/sequence).

Translation

[page 1]

(30600)

Sir,

The death of my son presents itself in

my spirit in different ways

such that I cannot prevent myself

from sharing it with you and letting [you] know

the worries that it gives me. Since

your departure, I have gathered information whether

any birds of prey were seen around

the plot of land. I was told no, which

is all the more surprising. This poor

boy can’t have just disappeared.

I am now coming to the idea that

that scoundrel Ponpé [Pompée] belonging to Mr. Chatant

killed him. What strengthens me in

this feeling is that the first

night that my son was missing,

a boat was taken from Nivet’s landing,

and that my son has arrested

[page 2]

(30601)

that rascal several times. I believe that

one would not risk much in arresting

that clown and interrogating him under torture.1

He cannot be far. He was at

Mr. Fleuriot’s at the dance. No one can take away

my feeling now that we will find

nothing that [ill.] if he [Corbin] has been killed, since it

is not credible that a man can disappear

in the way that he has if some misfortune of the kind that

I suspect hasn’t befallen him.

I believe that one must

not neglect to punish this scoundrel if

we can discover that he is guilty.

He could have been after my son because the

last time he [Corbin] caught him, he [Corbin] said to his

little brother [Pierot], who was driving him [Pompée] to M.

Chaperon that if [Pompée] wanted to escape,

to fire [his gun] at him, which Pierot did. His

[page 3]

(30602)

gun was only loaded with salt to

frighten him. And the other time that

he [Corbin] had caught him [Pompée], he had had him [whipped]. I have

every reason to suspect him [Pompée], as he is a

very bad subject. Your wife

is well. She greets you.

I have the honor of being most perfectly,

Sir,

your very humble

and very obedient

servant, Widow

the 26th June 1743 Baschemin

[page 4]2

To Monsieur

Monsieur Raguet

At New Orleans

A gunshot was fired at night [ill.]

have [ill.] the alcohol

presents made Bachemin [ill.] Petit Jean Leveillé

barre La fers [ill.] sa [fe] sa fille Lafleur a [baulne] [ill.]

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/06/26/01 (day/month/sequence).

List of Questions Prepared by the Attorney General for the Interrogation of Pompée (Liste de questions préparatoires preparées par le procureur general pour Pompée)

Transcription

List of Questions Prepared by the Attorney General for the Interrogation of Pompée[page 1]

(30608)

Faits admini[stré] [par] le procureur general

son nom [age] qualité demeure

sil [ill.] a etre maron et sil la ete [depuis]

Depuis quand il est de retour de son dernier mar[onnage]

Sil na pas ete depuis peu aux habitations de [dam.]

en bas ce quil y est allé faire et combien il y a

ce qui loblige a etre si souvent maron

[Si pendant] le temps de son maronage il nest pas [dam.]

pour vivre et sil nentra pas dans les maisons p[our]

quil y [volles?]

Sil na pas voles chez la sanschagrin dans la maiso[n] [de]

raguet

Si le Sr corbin [ne la pas arresté] et conduit chez chapro[n]

[Sil ne l’a pas fait] fouetter ou fouetté luy meme

Si cela nest pas [arrivé] plusieurs fois

Si led Sr corbin [ne la pas] fait conduire par son petit fre[re] [dam.]

dit de tirer sur luy sil vouloit senfuir et sil ny a pas [dam.]

coup de fusil chargé a sel

Sil ne scait pas ce quest devenu ledt Sr corbin

Sil la vu depuis peu ou sçu quil etoit allé en ch[asse]

ou luy [ill.] [etait le jour] de la feste dieu

sil ne court pas la nuit a pied ou a cheval prenant [des]

chevaux quil trouver a paistre

Sil na pas ete foüetté et marqué dune fleur de [lys]

Sil a pris une pirogue a lhabitation de livet ou sil [scait] [dam.]

prise et enlevée

Et tous autres resultants de ses reponses et quil plaira a [M.]

le Commissaire de suppleer

le vingt sept Juin mil sept cent quarante trois

Fleur[iau]

[page 2, blanche]

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/06/27/01 (day/month/sequence).

Le document est délavé et illisible le long de la marge droite.

Translation

[page 1]

(30608)

Facts administered [by] the attorney general.

His name, [age], status, residence?

If [ill.] to be a runaway and if he has been a runaway [since]?

Since when is he back from his last marr[onage]?

If he has not recently been by the plantations of the [dam.]

below, what he had gone to do there, and how much is there?

What compels him to be so often a runaway?

[If during] the time of his marronage he did not [dam.]

to live and if he didn’t enter into the houses in order

to [rob] them?

If he has not stolen from La Sanschagrin in the house [of]

Raguet?

If Sr. Corbin [hasn’t seized him] and taken him to Chapro[n]’s?

[If he has not had him] whipped or done it himself?

If this hasn’t [happened] a number of times?

If the said Sr. Corbin [hasn’t had him] driven by his little bro[ther] [dam.]

told him to shoot at him if he wanted to run away, and if he didn’t [dam.]

fire a gun loaded with salt?

If he doesn’t know what has become of the said Sr. Corbin?

If he has seen him recently or knew that he was going hu[nting]?

Where he [ill.] [was the day] of Corpus Christi?

If he doesn’t run around on foot, or on horseback, taking

horses that he would find at pasture?

If he has not been whipped and marked with a fleur-de-[lis]?

If he took a pirogue boat from the plantation of Livet or if he [knows] [dam.]

taken and removed [it]?

And all other [questions] resulting from his responses that it please [M.]

the commissioner to add.

The twenty-seventh June Seventeen forty-three.

Fleur[iau]

[page 2, blank]

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/06/27/01 (day/month/sequence).

The document is faded and illegible along the right-hand margin.

The Complaint (La Plainte)

Transcription

The Complaint(30606)

Messieurs Du Conseil Superieur de la [Province]

de la louisiane

Expose le procureur general du roy que le sieur [Corbin]

habitant a trois lieues de la ville a gauche du fl[euve]

ieudy matin treize de ce mois iour de la feste [dieu]

maison pour aller faire un tour de chasse [dam.]

quil dit et dans lintention de revenir sur le cha[mps] [dam.]

par un accident quon ne peult deviner il se [dam.]

ou egaré sans quon en ayt eu aucune nouvelle [dam.]

perquisitions quon ayt pu faire on na trouvé [aucune]

trace danimaux feroces qui eussent pu le de[vorer]

aucuns [n’est] [ill.] Le cadavre qui [dam.]

chaire pourie [ill.] qu’on Larreste a [ill.]

[ill.] assassine [ill.] La [ill.]

Sa lettre [ill.] nous Denonce pompee

esclave de [Sr Chapron] contre lequel elle a de [dam.]

soupcons entre autres de ce que ce negre est souven[t] [maron]

et que baschemin Corbin la arresté plusieurs fois la fa[ill.]

et la derniere fois quil le fist conduire par son f[rere]

Cadet il luy dist de tirer sur luy sil vouloit senf[uir]

Comme il voulut le faire il luy tira un coup de f[usil]

chargé a sel pour luy faire peur de sorte que ce [negre]

luy en veult il est connu pour un indigne coqui[n qui a]

été pris plusieurs fois pour vols et maronages [dam.]

condamne par arrest du Conseil a etre fouetté par [tous les]

[page 2]

(30607)

Carfours et marqué dune fleur de lys on peult le [croire]

Capable de touttes choses cest pourquoy ce Conseil

Vous plaise Messieurs ordonner qua la requeste [de]

la dame baschemin corbin et sur notre [f]onction ledit

pompee negre esclave soit arresté et constitué prison[nier?]

pour etre par lun des Messieurs quil vous plaira [ill.]

Commettre interrogé sur les faits qui seront administr[és?] pa[r]

la partie et sur ceux que nous donnerons et quil [soit]

informé du fait circonstances et dependances pour [dam.]

etre ordonné ce quil appartiendra a la nouvelle orle[ans]

le vingt septieme Juin mil sept cent quarante t[r]ois

Fleuriau

soit led. Pompée Negre1

[aprehendé de son corps]

es conduit dans les prisons

de cette ville pour [proceder a l’Ire]

[des fts] par Mr Prat

nommé a cet effet le 27 juin

1743 Salmon

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/06/27/02 (day/month/sequence).

Le document est délavé et abîmé sur la marge droite.

Translation

(30606)

Councilors of the Superior Council of [the Province]

of Louisiana,

The attorney general of the king sets out that Sieur [Corbin],

residing three leagues from the city to the left of the r[iver],

on Thursday morning the thirteenth of this month, the day of Corpus Christi,

[left his] house to go hunting [dam.],

as he said, and with the intention of returning straightaway [dam.],

by an accident which cannot be guessed, he [dam.]

himself or lost his way, and there hasn’t been any news of him [dam.]

[in spite of the] searches that were conducted. No trace has been found

of wild animals that could have devoured him,

nor has [ill.] the cadaver that [dam.]

rotting flesh [ill.] that we arrest him to [ill.]

[ill.] murdered [ill.] the [ill.]

Her letter [ill.] denounces Pompée,

slave of Sr. Chapron, against whom she has [dam.]

suspicions, among others that this negre is often [a runaway]

and that Baschemin Corbin has seized him several times [ill.],

and that the last time he did, he made his younger brother drive him back

and told him to fire on him if he wanted to run away.

As he wanted to do that, he fired his gun

loaded with salt at him to frighten him, with the result that this [negre]

resents him. He is known as a worthless scoundre[l] [who]

has been seized various times for theft and marronage

[and] condemned by the council to be whipped in [all the]

[page 2]

(30607)

quarters [of the city] and branded with a fleur-de-lis. We can [assume]

him capable of all things which is why this council,

if it please your honors, orders at the request of

the Dame Baschemin Corbin, and per our duty, that the said

Pompée negre slave be arrested and made a prisoner

to be, by whichever one of you it pleases to select, [ill.]

interrogated on the facts, which will be administered by

this party, and on those facts that we will give, and that he [the councilor] be

informed of the facts, circumstances, and dependencies, to

be ordered that which appertains. In New Orle[ans]

the twenty-seventh June seventeen forty-th[r]ee

Fleuriau

That the said Pompée negre1

[be apprehended by bodily arrest]

and conducted to the prisons

of this city to [proceed to the interrogatory]

[on the facts by Mr. Prat],

named for this purpose the 27 June

1743 Salmon

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/06/27/02 (day/month/sequence).

The document has faded and is damaged (torn/glue) on right margin.

Letter from Chaperon to Ordonnateur Edmé Gatien Salmon (Lettre de Chaperon addressée à l’ordonnateur Edmé Gatien Salmon)

Transcription

Letter from Chaperon to Ordonnateur Edmé Gatien Salmon[page 1]

A Lhabitation ce 24e

Aoust, 1743

Monsieur

Je prends La libertee de vous Ecrire ses ligne[s]

comme vous mavez chargée de vous Ecrire

se qui se passe au sujet du Naigre du Sr Leonnard

quy a dt Scavoire celuy quy a tuée M Corbin

Il Est Toujours maron cependant Londt

quil a Couchée deux nuit chez M Chamily

Sitot quil pourat Le voire Il luy dira

[page 2, blanche]

[page 3]

(30603)

De retournée chez Son maistre quil a Eu

Sa grace Et aubout de quelque Jours son mais[tre]

me Lenvoira pour cherchée des vivre[s] Et Je La

rettiré dans ma grange et Sur Le champs

Je ferré monter a Cheval p[r] avoir L’honneur

De vous avertire Voila Ce que nous somme

Convenus avec Le S Leonnard

Je finis En prenant La

Libertée de demeuré Le plus humble

De Vos petit Servitteurs

Chaperon

[page 4]

Le Monsieur

Monsieur De salmon

Intendant A La nouvelle

Orleans

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/08/24/02 (day/month/sequence).

Translation

[page 1]

At the plantation this 24th

August 1743

Sir,

I take the liberty to write you these line[s],

as you have charged me to write to you

about what is happening on the matter of the negre of Sr. Leonnard

who has said he knows the one who has killed M. Corbin.

He is still a runaway, however, it is said

that he slept two nights at M. Chamily’s.

As soon as he [Mr. Chamily] is to see him, he will tell him

[page 2, blank]

[page 3]

(30603)

to return to his master, that he has received

his grace, and after a few days, his mas[ter]

will send him to me to fetch provision[s], and I will

take him to my barn, and I will at once

send [someone] on horseback to have the honor

of warning you. That is what we have

agreed with S. Leonnard.

I end by taking the

liberty of remaining the most humble

of your lesser servants

Chaperon

[page 4]

Monsieur

Monsieur de Salmon

Intendant at New

Orleans

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/08/24/02 (day/month/sequence).

List of Questions Prepared by the Attorney General for the Interrogation of Jannot (Liste de questions préparatoires preparées par le procureur general pour Jannot)

Transcription

List of Questions Prepared by the Attorney General for the Interrogation of Jannot(30604)

[dam.] [ses] Responses [dam.]

Son nom age qualite et sil est ba[pti]sé

sil na pas souvent perdu le respect a son maitre

sil ne luy a pas dit quil mettroit le feu a sa cabane

pourquoy il luy a parlé ainsy quelle raison il a[voit]

[Si son maitre ne l’avoit pas gron] dé pour etre tro[p]

a la cabanne pour dejeuner

si en allant au desert il ne le menaça pas

sil ne luy dit pas quil scavoit qui avoit tué le S[r Corbin]

son voisin

pour quoy il ne veult pas le [dire]

si cest parce que ceux qui [l’ont] tué sont ses parents

ses amis et quils luy ont dit [de] ne rien dire

sil a ete aux badinage qui [sest fait] chez le sr corbin

avant sa mort

si lon y chanta des chansons [neg]res et en cette [dam.]

mort dudt Corbin

si on luy versa de leau ou de l’eau de vie sur la teste [dam.]

ce que cela vouloit dire

si les negres dudit Sr Corbin [scavent] aussy qui la tu[é]

sil a vu des rats attaches au hault de longues can[es] [dans]

le desert dudt Sr Corbin

sil scait qui les avoit mis la et a quel dessein

si dans le temps de la mort [dudt] Sr Corbin il y avoi[t] [des]

marons dans ces quartiers la

sil les connoist et sil ny en avoit pas un de lautre [côté]

qui est retourne chez son maitre

si ce negre scait aussy qui a fait ce coup

et tous autres resultant de ses reponses quil plaise

le commissaire de suppleer

ce neuf septembre mil sept ce[nt] quarante tro[is]

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/09/09/02 (day/month/sequence).

Document abîmé, avec des déchirures et de la colle.

Translation

(30604)

[dam.] [his] answers [dam.].

His name, age, status, and if he is baptised?

If he has not often lost his master’s respect?

If he hasn’t often told him that he would put fire to his cabin?

Why he had spoken to him that way, what reason he had?

[If his master hadn’t scolded him] for being too long

at his cabin for lunch?

If when he went to the plot of land he didn’t threaten him?

If he didn’t tell him that he knew who had killed Sr. [Corbin]

his neighbor?

Why he doesn’t want to [say]?

If it is because those who killed him [Corbin] are his parent[s] [and]

his friends, and that they told him not to say anything?

If he had been part of the fooleries [that happened] at Sr. Corbin’s

before his death?

If there was singing of [neg]re songs there and in that the [dam.]

death of the said Corbin?

If water or alcohol was poured over his head [dam.]

what that means?

If the negres of the said Sr. Corbin also [know] who had killed him?

If he has seen rats attached to the top of the long can[es] [in]

Sr. Corbin’s plot of land?

If he knows who put them there and for what purpose?

If at the time of [the said] Sr. Corbin’s death there wer[e]

runaways in the area?

If he knows them and if there wasn’t one on the other [side]

who has returned to his master?

If that negre also knows who did the deed?

And all others [questions] resulting from his answers which it please

the commissioner to add.

This ninth September seventeen forty-three.

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/09/09/02 (day/month/sequence).

Document damaged, with tears and glue.

The Complaint (La Plainte)

Transcription

The Complaint(30605)

A Messieurs Du Conseil Superieur de la

province de la louisiane

Expose le procureur general du roy quil a eu avis que

le nomme Jannot negre esclave du sieur leonard habitant

a trois lieues au dessous de cette ville a gauche du fleuve

setant mutiné contre son maitre il y a environ dou[ze]

a quinze jours luy avoit dit quil scavoit [dam.] qui est ce

qui avoit tué le Sr Corbin qui par un malheur

extraordinaire et quon na encore pu decouvrir dispar[ust]

le jour de la feste dieu derniere etant sorty de chez luy pour

aller faire un tour de chasse dans son dese[rt] [ill.] et devo[it]

revenir sur le champs touttes les perquisitions quon en a

faittes dans les [quartier on] na trouve ny le corps ny le fus[il]

Et hardes donnent lieu de penser quil [fault qu’on l’ait]

tue et enterre avec ses hardes et que ce pouvoit bien

ses negres ou ceux du voisinage, Jannot [dam.]

pres pouvoit bien en avoir ouy dire quelque [c]hose, dau[tant]

plus quil sest fait un service a la mode d[es] negres o[ù]

[dam.] ou lon pretend que la mort dudit Corbin fut ch[antée]

en langue negre precisement deux mois [dam.]

auparavant quelle arrivast, ce Janot au [dam.]

avois dit quil scavoit ceux qui avoint fait [ce] coup [son]

maitre homme fort agé et de bon renom e[st cr]oyable

cest pourquoy ce consideré

Vous plaise Messieurs ordonner que par [dam.] Messieu[rs]

quil vous plaira de Commettre led Jannot prison soit [inter]rogé pou[r]

ensuite ordonne ce quil appartiendra a la nouvelle

orleans le neuf septembre mil sept cent [quarante trois]

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/09/09/04 (day/month/sequence).

Le document est abîmé sur la marge droite, avec des déchirures et de la colle.

Translation

(30605)

To the Councillors of the Superior Council of the

province of Louisiana

The attorney general of the king states that he has been informed

that the so-named Jannot, negre slave of Sieur Leonard residing

three leagues below this city on the left [bank] of the river,

having mutinied against his master around twelve

to fifteen days [ago], had told him that he knew [dam.] who

had killed Sr. Corbin, who by an extraordinary misfortune

that has not yet been possible to discover, disappeared

the day of Corpus Christi last, having left his place

to go hunting in his plot of land [ill.] and was supposed to

return straightaway. Despite all the searches that were

made in the [area], neither the corpse nor the gun

and clothing have been found, giving rise to thinking that he must have been

killed and buried with his clothes and that it could well be

his negres, or those of the neighborhood. Jannot [dam.]

could well have heard say something, especially

since there was a service in the manner of the negres where

[dam.] it is claimed that the death of the said Corbin was chanted

in the negre language exactly two months [dam.]

before it happened. This Janot [dam.]

had said that he knew those who had done [this] deed, [his]

master, a very elderly man and of good renown, is credible,

which is why, this considered,

it please you sirs to order that by [dam.] sirs

that it please you to commit the said Jannot to prison to be interrogated,

then give orders accordingly. In New

Orleans, the ninth September seventeen [forty-three].

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/09/09/04 (day/month/sequence).

Document damaged on right margin—tears and glue.

Interrogatory of Jeannot (Interrogatoire de Jannot)

Transcription

Interrogatory of Jannot1

[page 1]

(30596)

[Interrogatoire

de

Jannot]

[paraphe]

[10 7bre]

(4427)

Lan mil sept Cens Quarante trois le dixieme

Septembre [au] matin A la Reqte du proc[ur]

Gnal du Roy. Nous Jean Pr[at] Consr.

au Conl superieur de la Louisianne sommes

transporté Es prison de cette ville a leffet

de proceder a LInterrogatoire dun Negre

Esclave apartenant a Leonard habitant [au]

detour aux Anglois, ou estant dans la

Chambre Criminelle [des] prisons

avons fait amener ledt Negre par

Le Geollier [des] prisons Lequel Nou[s]

ayant paru parler bon françois et

L’entendre pariellement [sic] avons procedé

aud Interrogatoire [ainsy] quil En suit.

Interrogé de son Nom age qualite et

Religion.

a dit se nommer [J]anots Negre Esclave

apartenant [a] Leonard Nation Bambara

age [d’]Environ trente [sept] ans et quil Est Baptise

Int[e]rrogé [a]pres [avo]ir promis de dire

verité pourquoy Il Est deten[ue] d[an]s les

prisons Et [qui Luy] a fait mettre

a dit quil Est detenu[e] En [prison parc]e quil

a dit quil Connoissoit Celluy qui a tue le sr Corbin

Prat

[page 2]

[2e] (30597)

Interogé sil Na pas souvent perdu le [respect]

a son Maitre

a dit que Nön

Interogé sil Ne luy a pas dit qu[il] [brulerai]

sa Cabanne

a dit quil y a longtemps Environ quatre ans

que Madame Vouloit le Battre parceque

il luy avoit Reproche de Ce quelle av[oit]

Battu sa femme plusieurs fois sans Raison

Et Notamment Ce jour la quelle donna [des]

souflet a sa [dite] femme qui avoit [pourtant]

Beaucoup Mal aux dents, ladte [dame]

Leonard prit une hache, En Menacant [le]

Negre de Les fraper Elle se Retire pourtant

Et alla Casser la porte de [sa] Cabanne

Cest alors que ledt Negre Luy dit qu[e]

sy Elle Continuoit il mettroit le feu a sa

Cabanne

Interrogé sy son maitre ne la pas souvent

Grondé pour Etre trop longtems a alle[r]

dejeuner

a Repondu quil y a Environ un Mois quil

travailloit a Cercler du Riz son maitre

Luy [Reprocha] de Ce [quil] Employait trop d[e]

temps a dejeuner Et luy fit plusieurs Mena[ces]

a quoy ledt [Jannot a] Repondit autre [C] [dam.]

[dam.] que luy Leonard Ne devoit pas t[ant]

[se facher] pour le temps quil Employoit

Prat

[page 3]

(30598)

dejeuner Ensuite ledt Leonard ses Ret[iré]

a La Maison Et ledt. janot sen fut aux Cha[mp]

Continuer son ouvrage, Et un moment apres

Voit Revenir son Maitre avec un fusil

Menacant ledt. Negre de tirer sur Luy

Et luy disant puisque tu as dit que tu

Voulais Me tuer Il faut que je te tue

a quoy ledt. janot Repliqua je Nay jamais

Eu la pensée de cela sy fait Bien dit ledt.

Leonard Car Ma femme Me la dit Et Bien

Mr. Luy dit le Negre sy Vous Voulez me

tuer me Voila je Ne Men Iray pas pour

Cela Vous Etes le Maitre

Interogé s’il na pas dit a son Maitre

quil scavoit qui a tué son Voisin Mr. Corbin

a Repondu que Non quil Na jamais parle de

Cela a son Maitre Et quil Ne Connoit point

Celuy qui a tué Mr. Corbin

interogé sil Na pas oüy dire que le Sr. Corbin

ayt Ete tué

a Repondu que Non

interogé sil Na pas Ete d’un Badinage

qui se fit Chez Lesr Corbin deux Mois

avant sa mort

a Repondu quil y a assisté mais quil Ny

Badinoit point

interoge sy Lon y Chanta des Chansons

Prat

[page 4]

(30599)

Negres Et En Cette langue la mort

de Sr Corbin

a dit que l’on Chanta Negre Mais quil nen[tend]

pas la Langue des Negres fonds [Fon]2 qui E[taient]

Ceux qui Chantoint

interogé sy lon Versa de leau ou de l’eau de vie

sur la tete dudt sr. Corbin En Chantant

Et Ce que Cela Voiloit dire

a Repondu quil Na point Veu Cela

interogé si les Negres du Sr Corbin

Scavent qui la tué

a dit quil Nen a aucune Connoissance Et que

sil Scavoit qui peut avoir tué ledt. Corbin

ou quil Connut des Gens qui le scavent

il Lauroit deja dit

interoge sil a Vu des Rats attaches

dans le desert dudt. Sr. Corbin au haut de

Longues Cannes sil scait qui les avoit

Mis la Et a quel dessein

a Repondu quil Nen scait Rien de tout

Cela Et quil Na pas Ete dans Ce desert

il a adjouté que le jour de la fete dieu

que ledt Sr. Corbin sest perdu il a passe

la journée Chez le Sr. Chaperon Et le lende[main]

Et jours suivants il a toujours travaille

avec son Maitre

Prat

[page 5]

(30609)

interogé sil a Connoissance que d[a]ns le temps

de la mort dudt sr. Corbin il y avoit de

Ce Coté la des Negres Marons

a Repondu que Non quil ne scait point

s’il y En avoit

interoge sil de lautre Coté de leau il

Ny avoit pas un Negre Maron qui Est

Retourné Chez son Maitre

a dit que les Negres de livet furent Marons

quinze jours apres la perte dudt sr Corbin

interoge s’il N’a pas Ete Maron Luy interogé

a dit quil y a Environ Cinq semaines il sen

fut Maron Et quil demeura huit jours

dehors Et que Ce fut parceque sa metresse

Vouloit L’emmener a la Ville pour le faire

fouetter pour les Mauvaises parolles Et

Raisonnements quelle disoit quil avoit

tenu a legard de son mary

Qui Est tout Ce quil a dit scavoir

Lecture a luy faite du present interogatoire

a dit que ses Reponses Contiennent Verite

y a persisté Et declaré ne scavoir Ecrire

Ny signer de Ce Enquis suivant Lordce

Prat

Soit Communiqué au procureur gnal

du Roy ce 10e. 7.bre 1743.

Prat

Vu le present Interrogatoire Je requiere pour le roy que ledt

Janot soit fouette iusqua ce quil avoue ce quil a dit a son

maitre a la nouvelle orleans le dixe septemb 1743. Fleuriau

[page 6, blanche]

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/09/10/01 (day/month/sequence), 1743/09/10/02.

Document abîmé, avec des déchirures et de la colle.

Translation

[page 1]

(30596)

[Interrogatory

of

Jannot]

[paraphe]

[10 October]

(4427)

The year seventeen forty-three the tenth

September in the morning, at the request of the attorney

general of the king, we, Jean Prat, councilor

of the Superior Council of Louisiana, have

transported ourselves to the prison of this city in order

to proceed to the interrogatory of a negre

slave belonging to Leonard, inhabitant of

Detour aux Anglais [English Turn], where, being in the

criminal chamber [of] the prisons,

w[e] had the jailer [of] the prisons

fetch the said negre, who,

seeming to speak good French and

understand it also, we proceeded

to the said interrogatory as follows.

Interrogated about his name, age, status, and

religion.

Said he was named Janots negre slave

belonging [to] Leonard, of the Bambara nation,

aged about thirty-[seven] years and that he is baptised.

Interrogated after [having] promised to tell

the truth why he is detained in the

prisons and [who] had [him] put there?

Said that he is detained in [prison because] he

has said that he knew the one who has killed Sr. Corbin.

Prat

[page 2]

[2nd] (30597)

Interrogated if he has not often lost the [respect]

of his master?

Said that no.

Interrogated if he had not told him he would [burn down]

his cabin?

Said that a long time ago, about four years ago,

that Madame wanted to beat him because

he had reproached her for having

beaten his wife several times without reason,

and notably the day when she gave

blows to his said wife even though she had

a very bad toothache. The said Dame

Leonard took an axe, threatening [the]

negre that she would hit them, she left however

and went to break the door of [their] cabin.

It was then that the said negre told her that

if she continued, he would set fire to his

cabin.

Interrogated if his master hasn’t often

scolded him for taking too long sitting down to the table

for lunch?

Replied that about a month ago [as] he

was working at binding the rice, his master

[reproached] him for spending too much

time at lunch and made several threats,

to which the said [Jannot] replied [other] [C] [dam.]

[dam.] that he Leonard should not always

[get angry] about the time that he took to

Prat

[page 3]

(30598)

have lunch, after which the said Leonard retired

to the house, and the said Janot went to the field

to continue his work, and a moment later,

he sees his master returning with a gun,

threatening to fire at the said negre,

and telling him, “Since you have said you

wanted to kill me I have to kill you,”

to which the said Janot replied, “I have never

had that thought.” “Yes you have,” replied the said

Leonard, “because my wife told me.” “Well then,

Monsieur,” said the negre, “if you want

to kill me here, I will not leave for

that. You are the master.”

Interrogated if he didn’t say to his master

that he knew who had killed his neighbor Mr. Corbin?

Replied that no, that he has never talked of

that to his master and that he didn’t know

the one who killed Mr. Corbin.

Interrogated if he hasn’t heard it said that Sr. Corbin

had been killed?

Replied no.

Interrogated if he had not been part of the foolery

that took place at Sr. Corbin’s two months

before his death?

Replied that he did attend it but that he

did not take part in the foolery.

Interrogated if there was singing there of negre songs

Prat

[page 4]

(30599)

and in that language [sung] the death

of Sr. Corbin?

Said that there was negre singing but that he does not understand

the language of the [Fon]2 negres who were

those who sang.

Interrogated if water or alcohol was poured

on the head of Sr. Corbin while chanting,

and what that means?

Replied that he had not seen that.

Interrogated if the negres of Sr. Corbin

know who killed him?

Said that he knew nothing of that and that

if he knew who could have killed the said Corbin,

or knew people who knew that,

he would already have said.

Interrogated if he has seen rats

in the plot of the said Sr. Corbin, tied to the top of

long canes, and if he knows who had

put them there and for what purpose?

Replied that he knows nothing about any of

that and that he has not been in that plot [of land].

He added that on the day of Corpus Christi

when the said Sr. Corbin got lost, he had spent

the day at Sr. Chaperon’s and the next day

and following days he had been working always

with his master.

Prat

[page 5]

(30609)

Interrogated if he knows if during the time

of the death of Sr. Corbin there were

in that area any runaway negres

Replied that no, that he does not know

if there were any

Interrogated if on the other bank of the water

there wasn’t a runaway negre who has

returned to his master

Said that the negres of Livet ran away

fifteen days after the loss of the said Sr. Corbin.

Interrogated if he has not himself been a runaway?

Said that about five weeks ago he had

run away and that he remained away eight days

and that it was because his mistress

wanted to take him to the city to have him

whipped for the bad words and

arguments which she said he had held

toward her husband.

Which is all that he has said to know,

the present interrogatory was read to him,

said his answers contained the truth,

persisted in this and declared not knowing how to write

nor to sign. This inquired in accordance with the ordinance.

Prat

To be communicated to the attorney general

of the king, this 10th September 1743.

Prat

Seen the present interrogatory, I require for the king that the said

Janot be whipped until he admits what he has said to his

master. In New Orleans the tenth September 1743. Fleuriau

[page 6, blank]

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans 1743/09/10/01 (day/month/sequence), 1743/09/10/02.

Document damaged, with tears and glue.

CommentaryIn September 1743, a thirty-seven-year-old man, Jannot, interrogated in connection with an investigation into the disappearance of a missing colonist named Corbin, made the earliest, and hitherto unknown, reference by an enslaved individual to Voudou (Voodoo) practices in Louisiana. In his interrogatory, Jannot was asked “if he had not been part of the foolery that took place at Sr. Corbin’s two months before his death” and “if there was singing of negre songs and in that language [sung] the death of Sr. Corbin.” He answered that he did attend and “that there was negre singing but that he does not understand the language of the [Fon] negres who were those who sang” (que l’on Chanta Negre Mais quil nen[tend] pas la Langue des Negres fonds [Fon] qui Et[aient] Ceux qui Chantoint). The prosecutor also queried him about rituals that he linked to the service, involving the pouring of water or alcohol and rats strung up on tall canes. Details of the service, though significant to the prosecutor’s inquiries into Corbin’s whereabouts and possible murder (not to mention of interest to historians), however, appear to have been of less importance to Jannot. For him, the most crucial element to his testimony would be seizing the opportunity presented by his appearance in court to document his wife’s violent mistreatment at the hands of their mistress, Dame Leonard. Though seemingly unrelated, the prosecutor’s focus on determining Corbin’s fate and Jannot’s intent in retelling his wife’s trauma are in fact two poles of the same court case, each reflecting a diametrically different view of the facts at hand and even more fundamentally about the nature of the real crime committed—the murder of a colonist or the abuse of an enslaved woman.1

The Court Case

Commentary – The Court CaseThe case originated with Corbin’s mother, the Widow Baschemin, who prompted the investigation into her son’s disappearance. Corbin was last seen on June 13, 1743, after hunting on his lands at Détour des Anglais (English Turn), a settlement about two and a half leagues or approximately nine miles downriver from New Orleans (Figure 1). He and his younger brother Pierot had had numerous run-ins with an enslaved man called Pompée (French for Pompei), belonging to a colonist named Chapron. Corbin had frequently sought to police Pompée’s actions and limit his movements, even capturing him (without authority) and threatening him with a gun before returning him to his master. There is no doubt that this informal surveillance and policing was common practice even if it is seldom recorded: white colonists looked out for one another, some of them taking the control and capture of Black bodies to another level, risking injury to other people’s slaves through threats, violence, and acts of cruelty. Offering details of her two sons’ interactions with the “scoundrel,” “clown,” and “very bad subject” (in French, rendered as “quoquin,” “drole,” and “tres mauvais suget”), the Widow Baschemin wrote directly to her acquaintance Attorney General Jean-Baptiste Raguet, begging him to investigate and interrogate Pompée under judicial torture.2

Figure 1

Unknown artist, Carte particuliere du flevue [sic] St. Louis dix lieües au dessus et au dessous de la Nouvelle Orleans u sont marqué les habitations et les terrains concedés à plusieurs particuliers au Mississipy, circa 1723. Edward E. Ayer Manuscript Map Collection. VAULT drawer Ayer MS map 30, sheet 80. Courtesy The Newberry Library, Chicago

This French map from circa 1723 shows the course of the Mississippi River (then known by the French as the Saint Louis River), delineating the various tracts of land and habitations of the French on both sides of the riverbank up and downriver from New Orleans. English Turn is shown on the right-hand side of the map, downriver from New Orleans.

Ultimately, two enslaved men would be sought for interrogation, one, Pompée, as a suspect, the other, Jannot, as a witness. Though believed to be responsible for Corbin’s murder, Pompée eluded capture, and the questions prepared by the prosecutor in advance for him lie unanswered in the court archives. The investigation slowed down until late August, when Jannot, an enslaved man belonging to a colonist named Leonard, was rumored to know who had killed Corbin. Jannot, unlike Pompée, was less fortunate in evading a justice system that sought to compel him to testify. He was a runaway at the time that the court decided to interrogate him, and the trial record is unusual in documenting the devious way that Jannot’s owner conspired with a neighboring slaveowner to seize him for interrogation. Lured in by a false promise of grace from his master, Jannot was instead dispatched to New Orleans for questioning.3

Labor, Violence

Commentary – Labor, ViolenceJannot’s interrogation would afford him several openings to detail the treatment he—and especially his wife—had received at the hands of their enslavers. First though, as with all interrogatories, the prosecutor asked Jannot to identify himself, and Jannot answered that he was thirty-seven years old, of the Bambara nation, and baptized (Figure 2). According to the clerk, he appeared “to speak good French and understand it also.” The prosecutor then proceeded to lay out a series of questions asking the enslaved man about his relationship with his master and prompting him to explain why he had run away. In his responses, Jannot revealed much more about his life than strictly necessary. For instance, his testimony illuminates much about his responsibilities cultivating rice. Rice was grown in Senegambia, where Jannot originated, and knowledge in Louisiana of this specialized crop can be traced to Africans brought from West Africa. The captain of the first slave ship sent to Louisiana from the African coast, L’aurore, which left Whydah on November 30, 1718, was given direct orders to purchase not only three to four barrels of rice suitable for cultivation but also a few slaves who knew how to grow the crop. In other words, it was not simply Africans’ labor that enslavers desired but their expertise as well. Jannot also volunteered details about the rhythm of his workday and the importance of mealtimes with his wife, showing how he used his position as a skilled worker in his negotiations with Leonard over labor conditions and breaks for lunch.4

Figure 2

N[icolas] de Fer, L’afrique, ou tous les points principaux sont placez sur les opservations de messieurs de l’academie royale des sciences, 1761. Département cartes et plans. GE D-11409. Courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Map of Africa by N[icolas] de Fear, 1761.

Although Jannot experienced violence at the hands of his master (Leonard once threatened Jannot directly with a gun), Jannot primarily took issue with Madame Leonard. Taking advantage of his platform as a witness to bring up the matter of his wife’s abuse at the hands of their mistress, Jannot informed the court that Dame Leonard frequently beat his wife “without reason” (sans Raison). Jannot had a long memory, describing in detail how four years earlier Dame Leonard had terrorized him and his wife with an axe, including one time when she was already suffering from a bad toothache. Perhaps Dame Leonard’s actions were motivated by her husband’s sexual depredations of Jannot’s wife, though nothing of this was said in court (silence about sexual abuse was the norm). Jannot also recounted how Dame Leonard threatened to have him sent to the city to be (publicly) whipped and riled up her husband against him, claiming that the enslaved man wanted to kill his master. It was her threat of whipping that at last compelled him to run away.5

Thanks to French legal procedure, Jannot could deviate as much as he wanted from the questions posed, but that did not mean the court would deviate from its investigation into the disappearance of the missing man to probe Jannot’s complaints. Violence against the enslaved was quotidian. Although enslaved people often pointed out abuse in court, Louisiana judges never once took action, to order an investigation or prosecute, despite that Article 38 of the 1724 code noir made it an offense for a slaveholder to “torture” or “mutilate” his or her slaves. In part this was because the law imposed a high bar on what was deemed criminal abuse of slaves. At the same time as it stipulated what an owner could be prosecuted for, it allowed slaveholders vast discretionary power “when they believe their slaves to have deserved it, to have them put in chains or beaten with sticks or ropes.” Though intended for slaveowners and slaveowners alone, this loophole, as the case demonstrates, permitted neighbors and other whites to take it on themselves to police other people’s slaves with impunity, as Corbin and his brother did. Jannot likely knew that the court would do nothing about his and his wife’s treatment and that the questions about why he had resisted his master and mistress and run away were not motivated by concern for his well-being. He also probably guessed that what he would say in court would get back to his owners. Yet still he talked about the abuse, with passion and emotion and righteousness.6

Voudou

Commentary – VoudouOn the matter of the events preceding Corbin’s disappearance and alleged murder, Jannot’s tone was flatter. The attorney general stated for the record that “a service in the manner of the negres” had taken place two months exactly before Corbin went missing “where [dam.] it is claimed that the death of Corbin was chanted in the negre language.” At no point did Jannot admit to knowing who had killed Corbin, but under questioning, Jannot said that yes he had attended the service. It was at that point that he added the information that “there was negre singing but that he does not understand the language of the [Fon] negres who were those who sang.” Jannot did not specify if he was referring to men or women, but it was likely both. Beyond qualifying his answer with the information that the service was led by Fon slaves, Jannot did not elaborate, and the court did not seem particularly interested beyond confirming that some ritual had occurred, including the detail, generated during the investigation, that either water or alcohol had been poured “on the head of Sr. Corbin while chanting.” (The information obtained by the prosecutor was apparently unclear, and the two words in French are similar: eau and eau-de-vie). Colonists would have been very attuned to this detail given the importance and power of water in French culture, as reflected in their religion, folklore, and superstitions. There was also the matter of the dead rats affixed to the top of canes on Corbin’s land, which must have unsettled unknowing onlookers. Jannot denied having been there or seen them.7

Jannot’s testimony offers precious details about Voudou practices two decades after the arrival of the first Africans in Louisiana. Although Louisiana Voudou is often discussed as a derivation of Haitian Vodou, owing to the mass influx of refugees from the Haitian Revolution to New Orleans from the 1790s through 1810, his interrogatory preceded their arrival by at least fifty years. As Gwendolyn Midlo Hall has pointed out, “African religious beliefs, including knowledge of herbs, poisons, and the creation of charms and amulets of support or power, came to Louisiana with the earliest contingent of slaves.” Colonist Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz, who managed the plantation of the Company of the Indies and its two hundred slaves from 1728 to 1731, derisively described African slaves as “very superstitious and attached to their prejudices and to trinkets that they name gris-gris.” Prior to Jannot’s testimony, the first known reference by an enslaved person in Louisiana to these practices was a 1773 court case in which a creole slave (therefore one born in the colony) was accused of obtaining a “gris-gris” amulet from a Guinea slave with the intent to harm his master. The amulet was made up of a concoction containing rotten pieces of the gall and heart of a crocodile, with a small stick to stir it. Voudou, of course, was only one of the many religious and spiritual beliefs, including religious syncretism and polytheism, practiced by the enslaved in Louisiana.8

That Jannot singled out the Fon is significant, for Vodun, from which Voudou derived, was the religion of the Fon people of the powerful Kingdom of Dahomey in what is now southern Bénin on the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa (Figure 2). It was from there in 1718, only twenty-five years before Jannot was interrogated, that the first two hundred enslaved Africans transported to Louisiana originated, enduring the Middle Passage on the very ship L’aurore that had brought the barrels of rice.9

How do we even begin to interpret the descriptions of Voudou included in the 1743 court case? On the one hand, we cannot presume to understand the precise meanings of services and rituals that were intended to be ephemeral, enigmatic, and resistant to easy interpretation. The investigation into Corbin’s disappearance clearly led to some intrusive information gathering (probably coerced), explaining the interrogator’s reference to the service, to the water or alcohol poured on Corbin’s head, and to the “rats in the plot of the said Sr. Corbin, tied to the top of long canes.” Perhaps it is enough that thanks to Jannot, we know of the presence of Voudou in 1740s Louisiana. That said, it is important to contextualize the references and to attempt to ascertain if the elements described were in fact signs of Voudou and Fon religious practices.10

When interrogated “if there was singing of negre songs and in that language [sung] the death of Sr. Corbin,” Jannot admitted he had attended the “service” (what the French dismissed as “Badinage” or “foolery”). He then deflected, denying knowledge of the language spoken or what was said: “There was negre singing but that he does not understand the language of the [Fon] negres who were those who sang.” Besides which, there was certainly no corroboration that the “service” had even been about Corbin, though the detail about water or alcohol being poured on Corbin’s head (or an effigy of Corbin), if correct, seems to point in that direction.11

Jannot elaborated on his answer by explaining that he was not close to the Fon slaves. Such enmity and animosity pop up quite frequently in trials. Jannot self-identified in court as Bambara, meaning he was non-Muslim and from Senegambia, the name referring to the territory in West Africa with the Senegal River on the north and the Gambia River on the south. Senegambia was the source for the majority of slaves brought to Louisiana, and the Bambara were captured from deep in the interior (present-day Mali), then marched to the coast (Figure 3).

Figure 3

“Representation of a Lott of Fullows Bringing Their Slaves for Sale to the Europeans . . . ,” in Samuel Gamble, “Log of the Slaver-Ship Sandown,” 1793–1794. LOG/M/21; MS1953–35. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, at “Slave Coffle, Sierra Leone, 1793,” Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, accessed July 22, 2021, http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/414

Differences, and tensions, existed among the members of different West African groups as well as between those groups and creole slaves born in the colony. Five years later, another trial took place based on events centered at the English Turn (a trial that contains passages in a Creole language). Pierrot, who was Bambara, denied being the accomplice of Charlot dit Karacou based on the fact that he, Pierrot, was “not a friend of the Creoles” (que Luy N’est Pas Camarade des Creolles) (Figure 2). As for the Bambara and the Fon, they could not be further removed, either in their geographic origins, or in terms of language, religious beliefs, and cultural practices. In spite of such enmities, religious, cultural, and social activities were shared. Dances, for example, frequently took place at various plantations, such as one at Fleuriau’s that is mentioned in the Widow Baschemin’s letter to the attorney general regarding her son’s interactions with Pompée (Figure 4). As a result, sociability and alliances were necessarily created. Jannot after all, was present, and quite likely participated, in the “service.”12

Figure 4

Agostino Brunias, A Negroes Dance in the Island of Dominica. Private Collection. Photo © Christie’s Images Bridgeman Images

The fundamental premise of Fon cosmology is that the world is filled with deities who connect the realms of the living and of the dead. They dwell in every aspect of the natural and material world and can be called on to intercede when individuals need to be empowered in conflicts, to achieve change, to generate opportunities, or to find solutions to difficulties. And as Cécile Fromont has shown, it is important to recognize that “with the slave trade, the meaning of evil changed in these Atlantic-facing regions of the African continent, from unbalances that fit within a set frame of political, social, and familial change, to deeply transformative events instigated by Europeans (war, famines, displacement, enslavement itself) that threatened and often shattered the established cosmological order.”13

Religious services were a primary means of gaining intercession. These incorporated chanting, dancing, drumming, and performative rituals led by spiritual leaders—male and female—whose authority came from their ability to channel the power of spirits. Possession by a particular God was at the core of these rituals, for it invoked divinity and by means of trances facilitated communication between deities and the possessed (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Plate 105. From Zacharias Wagener, “Theirbuch,” circa 1634–1641, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresden, Germany, in Cristina Ferrão and José Paulo Monteiro Soares, eds., Dutch Brazil, II (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1997), 193–194, at “Divination Ceremony and Dance, Brazil, 1630s,” Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, accessed July 22, 2021, http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1018

This image offers a rare visual representation, from Brazil in the 1630s, of a divination ceremony and dance. It is discussed in James H. Sweet, Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship, and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441–1770 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2003), 144, 150.

Beyond group rituals that incorporated chants, incantations, and spirit manifestations, Fon cosmology also gave a prominent role to power objects known as bocio (meaning a cadaver that possesses divine breath) and other assemblages of objects drawn from the natural world that are empowered in order to intercede with deities (Figure 6). The precise meanings of these assemblages, however, cannot be recovered. As Suzanne Preston Blier observes: “The works themselves are not meant ever to be ‘understood’ in a standard sense, but instead remain enigmatic and obscure to local residents and foreign observers alike. This . . . does not reflect an arbitrary desire to hide or cover the work’s hidden (‘secret’) meanings from foreign (or local) audiences, but rather has grounding in the highly personal psychodynamic roles these objects play in local communities and a certain understandable hesitancy in discussing works so closely tied with an individual’s innermost thoughts and fears.” Opacity is key to their potency, though there are a few general rules that help explain how the assemblages work.14

Figure 6

Unknown Artist. Human Figure (Bocio), early twentieth century. Wood, fiber, and feathers. Guinea Coast, Republic of Benin. 5 5/8 × 1 5/8 × 1 1/4 in. (14.29 × 4.13 × 3.18 cm). Charles B. Benenson, B.A. 1933, Collection 2006.51.461. Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn.

The combination of ligatures, rats, and canes referenced in the trial seems intentional and very likely significant, even if we can at best only speculate about their purpose and meaning. Specific deities in Fon assemblages were associated with particular materials, and assemblages put relationships and problems in tangible form. They did so through a process of transference based on the properties of the items selected for incorporation. Fon assemblages are characterized “by the striking diversity of objects and materials that are aggregated on to them, including skulls, iron, rope, cords, feathers, gourds, shells, cloth, and leaves. These sculptures are prepared by specialists called botonon, who are known for their manipulation of mystical powers. . . . Some of the figures, which are bound with string or cord, serve to attack one’s enemies, preventing them from causing harm. Other sculptures of this type draw upon the imagery and powers of nature: an attached dog’s skull, for example, provides watchful vigilance; an owl’s skull offers protection against sorcery.” Can these devotional practices be linked to the dead rats strung up on tall canes?15

Figure 7

Plate XIII. From P[ierre] J]acquis] Benoit, Voyage a Surinam: Description des possessions néerlandaises dans la Guyane (Brussels, 1839), at “La Mama-Snekie, ou Water-Mama, faisant ses conjurations,” Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, accessed July 22, 2021, http://slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2351

This lithograph illustrates P[ierre] J[acquis] Benoit’s description of a healing ceremony in the Dutch colony of Surinam, which he visited in 1831, and in which a woman known as a “Mama Snekie, mother of serpents, or Water Mama” offered a cure to a mother for her ill child. Note the human figures positioned on the shelf in the top right corner of the room.

In Benin, common rats are associated with transformation, and bush rats with intelligence and fertility, so they might have been utilized in assemblages that called up these traits. It is also possible that new meanings were created in Louisiana based on observations of indigenous fauna and flora, such as the wood rats that Charlot trapped. Neotoma floridana (the Eastern woodrat, also known as the pack rat or bush rat) can measure up to forty-five centimeters (eighteen inches) long, and its characteristics, as described by the colonist and naturalist Le Page du Pratz, are intriguing:

The Wood-Rat has the head and tail of a common rat, but has the bulk and length of a cat. Its legs are short, its paws long, and its toes are armed with claws: its tail is almost without hair, which serves for hooking itself to anything; for when you take hold of it by that part, it immediately twists itself round your finger. Its pile is grey, and though very fine, yet is never smooth. The women among the natives spin it and dye it red. It hunts by night, and makes war upon the poultry, only sucking their blood and leaving their flesh. It is very rare to see any creature walk so slow; and I have often caught them when walking my ordinary pace. When he sees himself upon the point of being caught, instinct prompts him to counterfeit being dead; and in this he perseveres with such constancy, that though laid on a hot gridiron, he will not make the least sign of life. He never moves, unless the person go to a distance or hide himself, in which case he endeavors as fast as possible to escape into some hole or bush (Figure 8).16

Figure 8

Rat de bois (detail). From [Antoine-Simone] Le Page du Pratz, Histoire de la louisiane . . . , II (Paris, 1758), 94. Courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

As for the tall canes, these were not cultivated sugarcanes (that crop had not yet been introduced to Louisiana) but could have been Arundinaria gigantea, or “giant cane,” a native species of bamboo shown in a drawing of the Yazoo fort that was framed (out of scale), top left, top center, and bottom right, by cane ravines (Figure 9). Native Americans used these long thick river canes for baskets, mats, and other uses, and they were edible when young shoots. Jean-François-Benjamin Dumont de Montigny commented that Africans also consumed parts of the plant: “In a time of great famine, there were some negroes in that country who fed themselves on the seeds of cane and made a very good porridge from it. The grain from this plant resembles the oats in France.” What possible symbolic value the canes might have held, however, is difficult to say.17

Figure 9

[Jean-François-Benjamin] Dumont de Montigny. Plan du Fort des Yachoux, concession de Mgr. le duc de Belle Isle et associex, detruit, 1729, [1747]. Map no. 6. From “Memoire de Lxx Dxx Officiere Ingenieur, contenant les evenemens qui se sont passés à la Louisiane depuis 1715 jusqu’a present,” map no. 6, 123. https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:z603vn54b.Courtesy Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center at the Boston Public Library

Note the tall canes on the lower left and the “ravine of cannes” (ravine of canes) at the top of this image of the plan of the Yazoo post drawn by Louisiana colonist Dumont de Montigny.

In addition to any special meanings derived from individual components, there is another possible explanation for the rats tied to the canes. Fon assemblages of objects were also tied and bound to sticks to be displayed in specific locations identified with particular spirits or else secured to trees or bushes as crop protection. That use alone would have been invaluable to an enslaved person with responsibility for crops and livestock. In 1748, Pierrot described how his master would have had him tied down to four posts and whipped if any of the cattle he was in charge of were to stray. In 1764, the elderly Jeannot was the one made to suffer the consequences of his master’s indigo crop failure.18

Yet Jannot denied knowledge of the rats. Was there a simpler explanation? In 1748, when Charlot dit Karacou was accused of killing a French soldier at the English Turn, he was described as trapping wood rats to sell to other slaves. Wood rats were edible and rather tasty, according to Le Page du Pratz: “The flesh of this animal is very good, and tastes somewhat like that of a sucking pig, when it is first broiled, and afterwards roasted on the spit.” Their known use for human consumption suggests that Charlot sold them as food rather than as skinned and dried carcasses. Could the rats tied to canes have been associated with trapping? The prosecutor did not seem to think so, for his investigation clearly led to the belief that there was more to the hanging rats than trapping, perhaps because there were additional substances or objects incorporated with the bound rats.19

Rituals in the Manner of the French

Commentary – Rituals in the Manner of the FrenchIf we swivel our perspective to the colonists who initiated the court case, to Widow Baschemin and the others who had observed unusual goings-on, we glimpse something of their anxieties, their dread of the unknown, and their disquiet over the religious services and rites of enslaved Africans in their midst and under their yoke. It is, however, important to note that Europeans had their own traditions that they exported to the New World, of secretive rituals and superstitions that could harm or protect. These included the concealment of dried animals; assemblages of items hidden within the walls of buildings (most commonly worn garments and especially single shoes); and apotropaic marks, ligatures, and knots meant to protect from harm. Were any colonists struck by the similarities with the dead rats strung onto canes and the other rituals referenced in the trial? Probably not, but these traditions undoubtedly shaped their beliefs, and their fears.20

What’s more, Louisiana was a Catholic colony. If anyone cared to look, perhaps there was yet one more similarity between the religious experiences of colonists and African slaves. Jannot had sought to avoid being implicated in the ritual service by stating that though he attended, “he does not understand the language of the [Fon] negres who were those who sang.” Yet understanding a language is not a precondition for participation. After all, Jannot was baptized in the Catholic church in conformity with the Article 2 of the 1724 code noir, and church services were conducted in the Tridentine tradition, and therefore in Latin (Figure 10). With the exception of priests and higher-ranking male colonists, virtually no one who attended Latin mass in New Orleans would have understood what was being said. Yet they would have participated experientially through gestures and rites, immersed in the smell of incense, chanting, invocations, and prayer. They would have witnessed the proffering of wine and wafer for Christ’s blood and body and the pouring of water on the head in the case of baptism. These acts occurred within a space where saints’ sacred relics were venerated, relics which could include fragments of physical remains, such as bone and hair, or sanctified objects, often cloth, that had come into contact with the fragments. Would the judges have made a connection between Catholic rituals and the “service in the manner of the negres”? Would Jannot have? Possibly.21

Figure 10

Bernard Picart. Messe solennelle ou Grand’ Messe. 1725. Engraving. Numéro d’inventaire: G.39042. Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris.

This eighteenth-century engraving shows the Tridentine or Solemn High Mass in a Catholic Church in France. Note the priest, deacons, and other male celebrants facing the altar, their backs turned to the attentive congregation as they celebrate mass sung in Latin. Click here for a videorecording of a Latin mass celebrated in 1962 that shows the importance of interactive rituals that engage the senses (sight, sound, taste of host and wine, smell of incense).

Conclusion

Commentary – ConclusionThis is in many respects an exceptional court case that lays bare the inner workings of an investigation, replete with private letters speculating about the circumstances of Corbin’s disappearance, finger pointing at potential suspects, and trickery used to catch a witness. It is also about communities of enslaved West Africans uncovering a space to practice their religion, not necessarily out of sight of colonists, and discovering through that practice a means of building community that brought together the members of different West African “nations” (to use the French term) who found themselves stranded in Louisiana. And, ultimately, it is about Jannot’s quest to protect his wife, recount their abuse, and air their grievances. As for Corbin, his body was never found.