Jeanot, 1764

An elderly man justifies running away because of ill-treatment and tells of the community support he received

CommentaryIn April 1764, sixty-five-year-old Jeanot was arrested for fugitivity. His case offers a rare first-hand account by one enslaved African who was elderly. Interrogated about his motives for running away, Jeanot did not deny doing so. Instead, he launched into a detailed explanation for why he had fled his master’s property, alluding to his labor, the crops he was responsible for—indigo and maize—and his master’s ill-treatment when the crops failed. He then went on to provide details of the community assistance he received while on the run, assistance that likely reflected his important role as an elder. Devoid of the support that his master owed him by law, the elderly man instead found succor from another slave, though it did not last, and Jeanot ended up living on the streets, begging for food. It was this visibility that precipitated his arrest.

The Court Case

Jeanot was apprehended by a “Mr. Desilets and his son,” who discovered him begging in the street and confronted him about his circumstances, eventually leading to his arrest. None of the Desilets’ first names were given, but they were clearly related, likely to Jeanot’s master, also Sr. Desilets, probably the elder Antoine-Marie Chauvin de Léry Désilets (known as Désilets). The Désilets family was one of Louisiana’s founding families. Starting in 1718, the Chauvin family had established plantations downriver from New Orleans, on the same bank of the Mississippi around the area previously occupied by the Tchoupitoulas Indian village. They were considered among “the finest and best cultivated of the concessions in the country, with mill and forges” (Figure 1). In a 1724 court document that referenced the plantation, Désilets’s father recounted how he and his brothers “together, out of an impenetrable forest, by force of labor, made a fine and fertile plain.” Father Pierre de Charlevoix concurred, describing the Tchoupitoulas plantations as being

in a very good condition, the soil is very fertile and has fallen into the hands of expert and laborious people. They are . . . three Canadian brothers of the name of Chauvin, who having brought nothing with them to this country but their industry have attained to a perfection through the necessity of working for their subsistence. They have lost no time, and have spared themselves in nothing and their conduct affords an useful lesson to those lazy fellows whose misery unjustly discredits a country which is capable of producing an hundred fold, of whatever is sown in it.

Left unspoken and made invisible in these accounts of the Chauvin family holdings was that the “labor” and “industry” that sustained them was the work of enslaved Africans.1

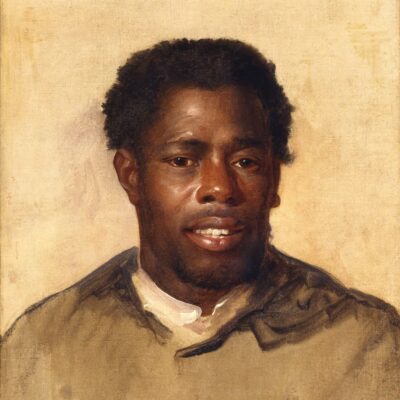

Figure 1

Unknown artist, Carte particuliere du flevue [sic] St. Louis dix lieües au dessus et au dessous de la Nouvelle Orleans u sont marqué les habitations et les terrains concedés à plusieurs particuliers au Mississipy, circa 1723. Edward E. Ayer Manuscript Map Collection. VAULT drawer Ayer MS map 30, sheet 80. Courtesy The Newberry Library, Chicago

This French map from circa 1723 shows the course of the Mississippi River (then known by the French as the Saint Louis River), delineating the various tracts of land and habitations of the French on both sides of the riverbank both up and downriver from New Orleans. Note the distances between the De Léry Désilets plantation, where Jeanot was enslaved; Bayou Saint Jean, where he found shelter and support with Jacob; and the town of New Orleans, where he was captured.

Indigo, Labor, and Old Age

When Jeanot identified himself to the court, he did not specify whether he was born in Louisiana or in West Africa, nor did he give an ethnonym (what the French called his “nation”). We also do not know when Désilets acquired Jeanot. Jeanot was not among those Désilets purchased in 1750 from the late Dame Anne Bertin’s estate. Given Jeanot’s age, he could have been among the eighteen enslaved individuals Désilets and his two siblings inherited from their father in 1734. By 1773, when the plantation was appraised, it consisted of “18 arpents front by 23 deep, surrounded by fences divided into four parts, situated four leagues distant from the city above on this side of the river, containing a house, warehouse, indigo mill, kitchen” and thirty-nine enslaved Africans “of all ages and sex” (Figure 2).2

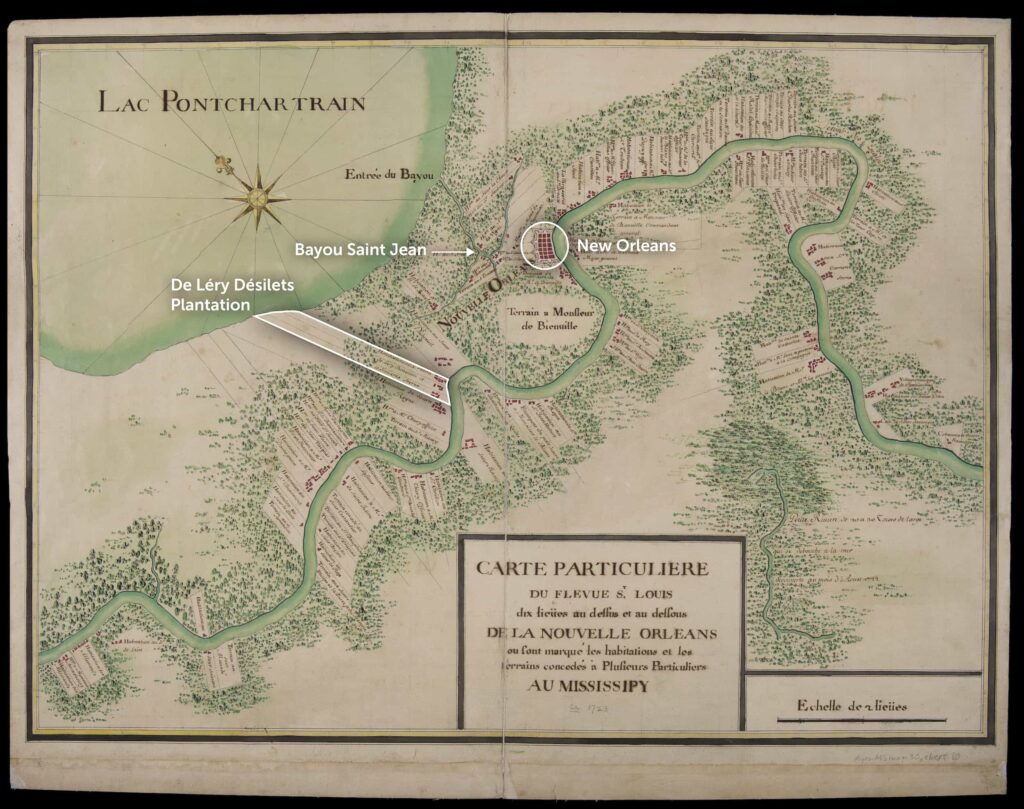

Figure 2

[Jean-François-Benjamin] Dumont de Montigny, “Concession des chaoüachas appartenante cy devant a mgr. le duc de bellisle et associez,” 1747. From Dumont de Montigny, “Mémoire de Lxx Dxx officier ingénieur, contenant les evenements qui se sont passé à la Louisiane depuis 1715 jusqu’à present: ainsi que ses remarques sur les moeurs, usages, et forces des diverses nations de l’Amerique Septentrionale et de ses productions,” 1747. VAULT oversize Ayer MS 257. Edward E. Ayer Digital Collection. Courtesy The Newberry Library, Chicago

Dumont de Montigny’s 1747 watercolor shows one Louisiana plantation, the Chaoüachas, which included indigo works. He also signaled the location of the plantation’s segregated cabins that housed its enslaved workers.

Indigo, referenced by Jeanot in his interrogation, was one of the staple crops grown for export on Louisiana’s plantations. In 1742, Désilets contracted with his father’s widow, Madame Laurence Le Blanc, to have indigo processing equipment constructed for the plantation (Figure 3). Crucially, as part of the agreement, Désilets was to furnish her with “four male negres for two and a half months,” presumably to help her build the machinery but also to be trained in its use. Jeanot might have been among this group. The leaves and stems of the indigo plant were harvested to make a valuable bright blue dye for cloth through a delicate, sometimes dangerous, and technologically complex method (Figure 4). Although enslaved women worked in the fields to grow indigo, only men were given the skills to operate the equipment. Since indigo cultivation and dyeing were well established in West Africa, Jeanot, depending on his origins, might have already had some familiarity with the plant, even if French methods and equipment differed slightly from West African techniques and dye pits.3

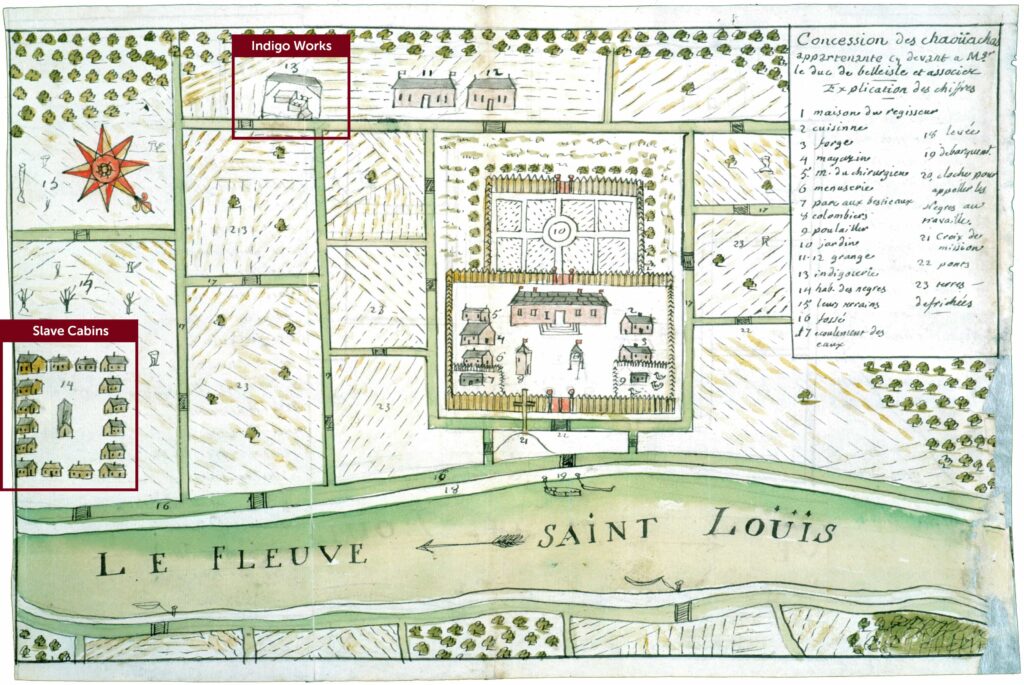

Figure 3

Indigoterie. From [Jean Baptiste] DuTertre, Histoire generale des Antilles habitées par les françois . . . , II (Paris, 1667), foldout plate following p. 106, at “Indigo Production, French West Indies, 1667,” Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, http://slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1205

Engraving published in 1667 showing the type of indigo cultivation and indigo works that the French established in the Antilles.

Figure 4

“Toilles de Cotton peintes à Marseilles,” 1736. Tissus de XVIIIe siècle. Collection Richelieu. Département Estampes et photographie. RESERVE LH-45-BOITE-FOL 29-nos. 133–140. Courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Samples of surviving French-manufactured printed cottons from 1736 with a blue indigo ground.

Whereas indigo was grown for export, maize, the crop Jeanot was responsible for, was a staple of Louisiana’s domestic trade. Watching over fields of maize was the kind of occupation that elderly slaves such as Jeanot were often assigned. Unlike indigo, maize was vulnerable to depredations by animals, including domesticated livestock that roamed freely. Reflecting the brutal reality that slaves, for owners, were, above all, commodities, the lower productivity of elderly enslaved men and women like Jeanot meant that they were valued at a lesser rate than younger enslaved people, or even deemed worthless. As one slaveowner argued in court when sued for payment or the return of four enslaved men purchased in 1752, not only had one of them died in the intervening period, but “if they were taken back, wherever they are put for sale, because of their old age they will never be sold for more than half the price of their purchase.” In contrast, Jeanot could expect to receive respect within the slave community, for in West Africa, elders were revered.4

Community Support for Runaways

Under questioning, Jeanot acknowledged having been a runaway for about five months, leading the court to prompt him to explain how he had survived. The interrogators, keen to use Jeanot’s testimony to wheedle information from him about other runaway networks and to identify those who helped them, asked him a series of leading questions that brought to light the community support he received at Bayou Saint Jean, specifically from the enslaved Janot (Figure 5). The help that other enslaved persons offered to runaways was often crucial to their survival. The type of community support varied, but it was neither insignificant nor undertaken lightly. Janot knew he was taking a risk in helping the runaway, but he nonetheless provided succor to Jeanot, understanding full well that it was his duty and that it was crucial to the elder’s survival. As it was, Jeanot broke his trust by naming Janot in court. Janot was not prosecuted, but his master undoubtedly punished him.5

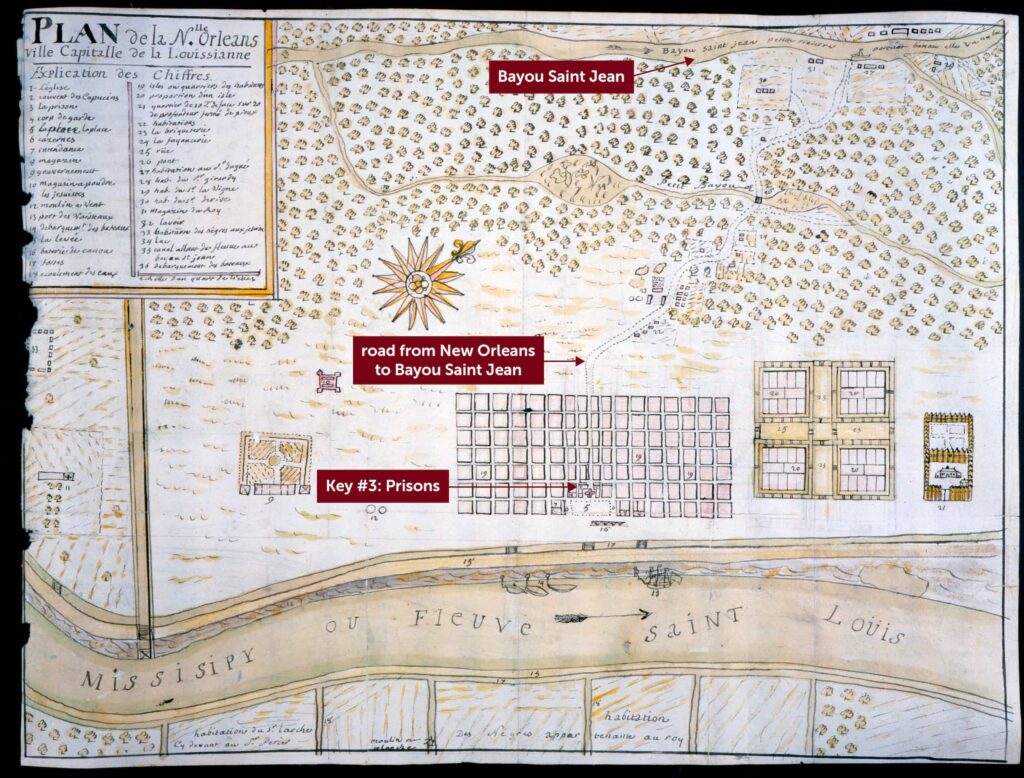

Figure 5

Jean-François-Benjamin Dumont de Montigny, Plan de la Nlle. Orleans, ville capitalle de la Louissianne, [1747]. Edward E. Ayer Manuscript Map Collection. Vault oversize Ayer MS 257, map no. 7. Courtesy of The Newberry Library, Chicago

In Dumont de Montigny’s 1747 map of New Orleans, Bayou Saint Jean is signaled on the upper right. Note in this watercolor how de Montigny carefully identifies the well-trod path from the town to Bayou Saint Jean.

Jeanot was not the only one of Désilets’s slaves to seek to escape during this period. In July the same year, Charlot was caught and prosecuted for running away. Augustin Poliche was also arrested in July. He described how he “had stayed all the time behind his master’s plantation and lived off potatoes, which he cooked with fish that he fished with the fishing rod that he had taken with him, and that some days he went without eating the whole day” (a dit qu’il a toujour resté derriere l’habitation de son maitre et qu’il a vecu avec des pommes de terre, qu’il faisoit cuire avec du poisson qu’il pechat a la ligne qu’il avoit emporté avec luy et quil a été des jours entier sans manger). The following year, in February 1765, another of Désilets’s slaves, Essom, of the Nago nation, was apprehended.6

As for Jeanot, the judges convicted him of running away. Despite that Article 20 of the 1724 code noir required the Superior Council of Louisiana to investigate and prosecute masters who failed to properly feed, clothe, and provide for their slaves and Article 21 specifically stipulated that older and infirm slaves abandoned by their masters be adjudged to the nearest hospital and their masters charged for their food and maintenance, the judges chose not to investigate Jeanot’s claims of neglect on the part of his master. The court turned a blind eye to its own laws and showed Jeanot no mercy. In conformity with Article 32, pertaining to slaves who had run away for longer than thirty days, they sentenced the sixty-five-year old to have his ears cut, to be branded with a fleur-de-lis (a stylized lily that was the symbol of the French crown) on the shoulder, and to be returned to Désilets (Figure 6).7

Figure 6

Unknown, Histoire véritable et facécieuse d’un espaignol, lequel a eu le fouet et la fleur de lis dans la ville de Thoulouze pour avoir dérobé des raves et roigné des doubles, 1630. Engraving. Recueil. Collection Michel Hennin. Estampes relatives à l’histoire de France. Tome 27, pieces 2313–2409, période: 1630–1632. Collection Michel Hennin, 2361. Département Estampes et photographie. RESERVE QB-201 (27)-FOL. Courtesy Bibliotheque nationale de France

In this rare depiction of a judicial branding, we see a hot iron shaped like a fleur-de-lis being applied to the right shoulder of a convicted criminal in 1630 France.

Links

Link 1: Indigo

A. Trabalho do terreno para se plantar hum Indigoal, e para o colher. From Josè Mariano da Conceicao Velloso, O fazendeiro do Brazil, cultivador . . . , II (Lisbon, 1806), Plate 1, foldout following p. 341 (copy in the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, Providence, R.I.), at “Cultivation of Indigo, French West Indies, Late 18th Cent.,” Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, http://slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1146)

B. Indigoterie. From [Jean Baptiste] DuTertre, Histoire generale des Antilles habitées par les françois . . . , II (Paris, 1667), foldout plate following p. 106, at “Indigo Production, French West Indies, 1667,” Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, http://slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1205

C. “Toilles de Cotton peintes à Marseilles,” 1736. Tissus de XVIIIe siècle. Collection Richelieu. Département Estampes et photographie. RESERVE LH-45-BOITE-FOL 29-nos. 133–140. Courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

D. Baba Coulibaly and Mohomodou Houssouba, “Lifelong Learning with Indigo in Mali: Seeing Blue and More with Groupe Bogolan Kasobane,” International Institute for Asian Studies, The Newsletter, 87 (Autumn 2020), 48–49, https://www.iias.asia/the-newsletter/article/lifelong-learning-indigo-mali-seeing-blue-and-more-groupe-bogolan-kasobane

E. “Slavery in Louisiana: The Whitney Plantation,” Whitney Plantation, https://www.whitneyplantation.org/history/slavery-in-louisiana/

Interrogatory of Jeanot (Interrogatoire de Jeanot)

Transcription

Interrogatory[page 1]

pre-page No. 1832

[paraphe de Garic]

12 [avril] 1764.

Interrogatoire

du nègre [Jea]not

Interrogatoire fait par nous Louis piot de Launaÿ

Conseiller Commissaire en Cete partie au nommé Jeanot

Negre appartenant auSr. Desilotz1 a La Requette de Mr. Le

procureur gl. Du Roÿ et En Vertu de Lordonnance de Mr.

Dabbadie Directeur general et Commandant pr. Le Roÿ

La province de La Loüizia[ne] et per. Magistrat au Conseil

Superieur Dicelle. En datte de Ce Jour Douze avril

Du 12. avril 1764.

a Eté emmené Des prizons Roÿalles de Cette Ville en La

chambre Criminelle de Justice Le nommé Jeanot

Negre appartenant a Mr. Desilets. Le quel a pris serment

par Luÿ prété de Dire verité sur Ce quil seroit par

nous interrogé a Dit Sappeller [Jeanot] agé de

soixante et Cinq ans, catholique apostolique et Romaine

Interrogé pour quoÿ il est En prizon et qui Lŷ a fait

metre, et Combien de tems il ÿ avoit quil etoit

En prizon.

A Dit que Mr. Desilets et son fils2 La voient trouvé

Dans La Rue demmandant La charité, et Luÿ

avoient dit pourquoÿ il etoit dans La Rue et

quil Leur avoit Repondu que naÿant rien a

manger dans Lhabitation, il etoit obligé de Mandier

pour vivre, que L’Été dernier son Maitre naÿans

point fait dindigot setoit attaché a faire beaucoup

de Mahis, [Lequel] Mahis Le dit negre etois chargé

pour Le garder, qui nonobstant ses soins Comme Cette

terre netoit point entourée, Les cheveaux ne Laissoint

pas que dentrer et chevreuils, Et faire beaucoup

de Ravages, que son Maitre faché Le maltroitoit

Cer DeLaunay

Garic Greffer

[page 2]

Seconde page

et pendant tout Lhiver ne Luÿ auroit donné

La moindre choze ni Capot ni chemize pour

se prezerver des inclemences de La Rude saison

et a Dit quil ÿ a environ Cinq mo[is] qu’il est

Marron par Raport a Cela.

Interrogé qui est Ce qui L’avoit nourri pe[ndans]

son Marronage, et ou Est ce quil avoit Resté pendant

Le dit temp

a Dit quau Baÿou St. Jean près du Corps de garde

il avoit rencontré Le negre Janot appartenant

a Mr. Dubois, qui Luÿ dit Reste avec moÿ Je te

nourrirai et t’abillerai quil ÿ avoit Resté avec Luÿ

Environ trois mois, et qu’ensuite il Revint a La

Ville Mandier son pain, qu’en tous temp il avoit

Resté environ Cinq mois Dans son Marronage

et quil alloit toujours, Coucher au bord de Leau

où il fezoit Du feu, naÿant Jamais Couché dans

aucunne Cabanne

Interrogé sil n’avoit volé personne pendant son

Marronage [?] et sil n’avoit Recu aucuns secours

des autres Negres Marrons.

a Dit quil n’avoit pas volé un poille, ni

Rencontré aucun negre Marron.

Interrogé si Les negres qui tuoient vaches ou voloient

Bestiaux ne Luÿ en avoit point volé.

a Dit que Non et quil navoit vü aucun negre

Marron, et que sil ÿ avoit été Luÿ meme Cest

que son Maitr[e] ne Luÿ donnoit aucuns vivres

ni aucuns habits pour Le Garantir Du froit

[page 3]

Troisieme et d.re page

DeLaunay

qui est tout Ce quil a Dit scavoir

Lecture a Luÿ faite du prezent interrogatoire

a Dit ses reponses Contenir verité, ÿ a persisté

et n’a scu signé de Ce Enquis etc

DeLaunay

Garic Greffr

Ce fait avons fait ramener Le dit Negre dans

Les prizons Roÿalles par Le Geolier et avons

ordonné et ordonnons que Le prezent, interrogatoire

sera Communiqué au procureur General du

Roÿ pour ÿ prendre Droit et Requerir Ce quil

appartiendra et avizera.

Donné en La chambre Criminelle de

Justice Le Jour et an sus dit

DeLaunay

Garic Greffr

[page 4, blanche]

[page 5]

Vu le proces Criminel extraordinairement instruit

a ma requeste Contre le Négre nommé Jeannot appt.

Au Sr. Desislet[re] accusé et prisonnier en prison civiles

de cette Ville

Ma requeste pour que ledt. Negre soit interrogé du

12. Avril 1764.

l’ordonnance Au bas du premier juge de meme datte

Qui nomme M. Delaunay Conseiller Commissaire

raporteur

linterrogatoire Subi parled. Accusé de meme jour

Je Requiere pour le Roi que led. Négre nommé

Jeannot Accusé et prisonnier es prisons civiles de

Cette Ville soit declaré duement atteint et Convaincu

d’estre Maron depuis cinq mois pour reparation

de quoy qu’il soit Condamné a avoir les oreilles Coupées

et estre marqué d’une fleur de Lis sur l’epaule dextre

par l’executeur de la haute justice, que l’arrest a intervenir

sera lû, publié et affiché es lieux accoutumés et que Copies

Collationnées en seront envoiées dans les postes A la Nlle

Orleans le 14 avril 1764.

Lafreniere

[pages 6, 7, 8, blanches]

[page 9]

A Monsieur Dabbadie commandant Pour Le3

Roy commissaire general de la marine, et Premier

juge au Conseil Superieur de la Province de La

Louisianne

Remontre Le Procureur general du Roy audt. conseil

quil y a dans Les Prisons civille un negre nommé

jannot appartenant A Mr desillets atteint et

convaincu de maronage comme le delit interesse

La vindicte Publique je Requiere pour Le Roy

que ledt. negre soit [murement] interrogé sur ledt fait

de maronage, circonstance et dependence par tel

commissaire quil Plaira nommer pour ledt interrogatoire

metre communique Etre Requis ce qui de droit et

etre ordonné ce quil appartiendra a la nlle orleans

Le 12 avril 1764

Lafreniere

Soit Ledt. negre interrogé par M delaunay cons[r]

comre nommé en cette Partie pour ledt. interrogatoire

etre communiqué au Procureur general du Roy

etre Requis ce que de droit et etre ordonné ce quil

appartiendra a La nlle orleans Le 12 avril 1764

Dabbadie

[page 10, blanche]

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans, 1764/04/12/01 (year/month/day/sequence).

Translation

[page 1]

pre-page No. 1832

[paraphe of Garic]

12 April 1764

Interrogatory

of the negre Jeanot

Interrogatory made by me, Louis Piot de Launaÿ,

councilor commissioner in this part, of the named Jeanot,

negre belonging to Sr. Desilotz, at the request of the

attorney general of the king, and according to the order of Mr.

D’Abbadie, director general and commander for the king of

the province of Louisiana and first magistrate of its Superior

Council. Dated this day twelfth April.

12 April 1764

Has been brought from the royal prisons of this town into the

criminal justice chamber the named Jeanot,

negre belonging to Mr. Desilets, who has sworn

to tell the truth, whereupon was

interrogated by us and said he was named [Jeanot] aged

sixty-five years, Roman Catholic and Apostolic.

Interrogated why he is in prison and who had him

put there, and how long he had been

in prison?

Said that Mr. Desilets and his son1 had found him

in the street asking for charity and

had said to him, “Why was he in the street,” and

he had replied that having nothing to

eat at the plantation he was forced to beg

to live. That the previous summer his master, having

made no indigo, had decided to grow a lot

of maize, which maize the said nègre was charged

with watching, that notwithstanding his care, as this

land was not fenced in, the horses kept

coming in, and the deer [also], and made much

damage. That his master was angry, ill-treated him,

C[ouncil]or DeLaunay

Garic clerk

[page 2]

Second page

and during the whole winter did not give him

the slightest thing, neither capot2 nor shirt,

to protect himself from the inclemencies of the harsh season,

and said that it is since about five months that he is

a runaway because of this.

Interrogated as to who had fed him during

his marronage and where he had stayed during

the said time?

Said that at Bayou Saint Jean near the guardhouse

he had met the negre Janot belonging

to Mr. Dubois, who told him, “Stay with me I

will feed you and dress you,” that he stayed there with him

for about three months, and that afterward he returned to the

town to beg for his bread, that during that entire time he had

stayed about five months a runaway,

and that he always went to sleep by the water’s edge

where he made his fire, having never slept in

any cabin.

Interrogated if he had stolen anything from anyone during his

marronage and if he had not received any help

from other runaway negres?

Said that he had not stolen one hair nor

met any other runaway negre.

Interrogated if the negres who killed cows or stole

livestock had not stolen any for him?

Said that no and that he had not seen any

runaway negre, and that if he had been one himself

it was because his master gave him no food

nor clothes to protect him from the cold.

DeLaunay Garic clerk

[page 3]

Third and last page

DeLaunay

Which is all that he said he knew,

the present interrogatory was read back to him,

said his responses contained the truth, persisted in this,

and did not know how to sign, this inquired [of him], etc.

DeLaunay

Garic clerk

This done, we had the said negre taken back to

the royal prisons by the jailer and have

ordered and do order that the present interrogatory

be communicated to the attorney general of the

king to consider it and require that which

appertains and that he advises.

Given in the criminal justice

chamber the said day and year.

DeLaunay

Garic clerk

[page 4, blank]

[page 5]

Seen the criminal procedure extraordinarily instructed

at my request against the negre named Jeannot belonging

to Sr. Desislet[re], accused and prisoner in the civil prisons

of this town.

My request for the said negre to be interrogated,

dated 12 April 1764,

the order at the bottom [of the page] from the first judge of the same date

Which names M. Delaunay councilor commissioner

and reporting judge,

the interrogatory undergone by the said accused of the same date,

I require for the king that the said negre named

Jeannot, accused and prisoner in the civil prisons of

this town, be declared duly convicted

of being a runaway for five months for reparation

of which he be condemned to have his ears cut

and to be branded with a fleur-de-lis on the right shoulder

by the executor of high justice3, that the judgment

will be read, published, and posted in the customary places, and that collated

copies will be sent to the posts4. At New

Orleans the 14 April 1764.

Lafreniere

[pages 6, 7, 8, blank]

[page 9]

To Mr. D’Abbadie commander for the5

king, commissioner general of the Marine, and first

judge of the Superior Council of the province of

Louisiana,

the attorney general of the king at the said council

advises that there is in the civil prisons a negre named

Jannot belonging to Mr. Desillets duly

convicted of marronage. As the offense concerns

the public good, I require for the king

that the said negre be carefully interrogated on the facts,

circumstances, and dependencies of his marronage, by such

commissioner as it pleases him to name for said interrogatory,

this to be communicated to me, this so requested

and ordered that which appertains. At New Orleans

the 12 April 1764.

Lafreniere

Ordered that the said negre be interrogated by M. Delaunay, councilor

commissioner named in this part to conduct said interrogatory,

to be communicated to the attorney general of the king,

and be requested by rights and be ordered that which

appertains. Made in New Orleans the 12 April 1764.

D’Abbadie

[page 10, blank]

Source: Records of the Superior Council of Louisiana (1717–1769), Louisiana History Center, Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans, 1764/04/12/01 (year/month/day/sequence).